It was a delightful villa. A view across Eden Park. High ceilings giving a feeling of space.

Of course, it wasn’t perfect. A shared driveway thanks to the cut-up of cross-leasing. The street parked up and clogged during rugby matches. A worn interior from years of tenants.

But we were at the auction. A first home for my wife and I. With an agreed maximum bid.

The starting price was 400k. First bid 410. Then 420. 430…

The real-estate agent goaded me. ‘You’ll never get this opportunity to buy here again!’

I caught my wife’s glance. She was shaking her head.

Some time later, we ended up on the North Shore. With a home looking over the sea.

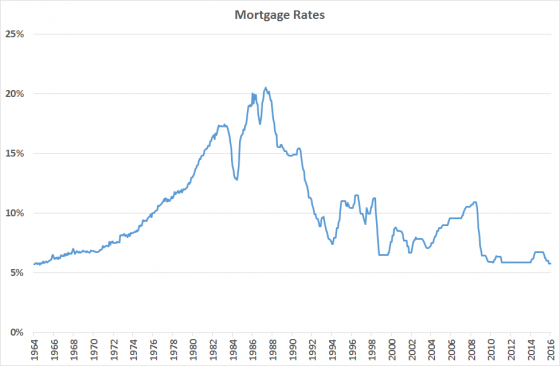

Back then, mortgage interest rates were around 8%. Now, I have pause to wonder, at 3%, whether we might have put in a higher bid for that villa. And started much of our married life in Mt Eden.

Then again, other bidders might have felt the same way.

This is how The Price of Money works. When it’s prevalent and cheap, we’re inclined to borrow more. Spend and bid more. Rather than have it sit in the bank, earning little.

Central banks are decreasing the price of money again…

On March 3, the Reserve Bank of Australia cut the cash rate to a new record low of 0.5%.

In the US, the Federal Reserve announced an emergency cut, reducing the benchmark to 1% to 1.25%.

In Europe, the ECB rate sits at -0.5%, and in the UK, the Bank of England base rate is at 0.75%. Bets are siding toward cuts in both.

And here in NZ, the Reserve Bank is being called on to slash another 25 to 50 basis points. Which appears inevitable since the coronavirus is having an outsized impact on this small economy.

Trump has been demanding interest rate cuts for years. Claiming the previous higher US rates put his country at a disadvantage.

Now he’s wanting more.

Because, in normal circumstances, low interest rates are a friend of the stock market.

Indeed, commentators are pointing at the recent rate cuts as surety that no economy wants the bull run to end.

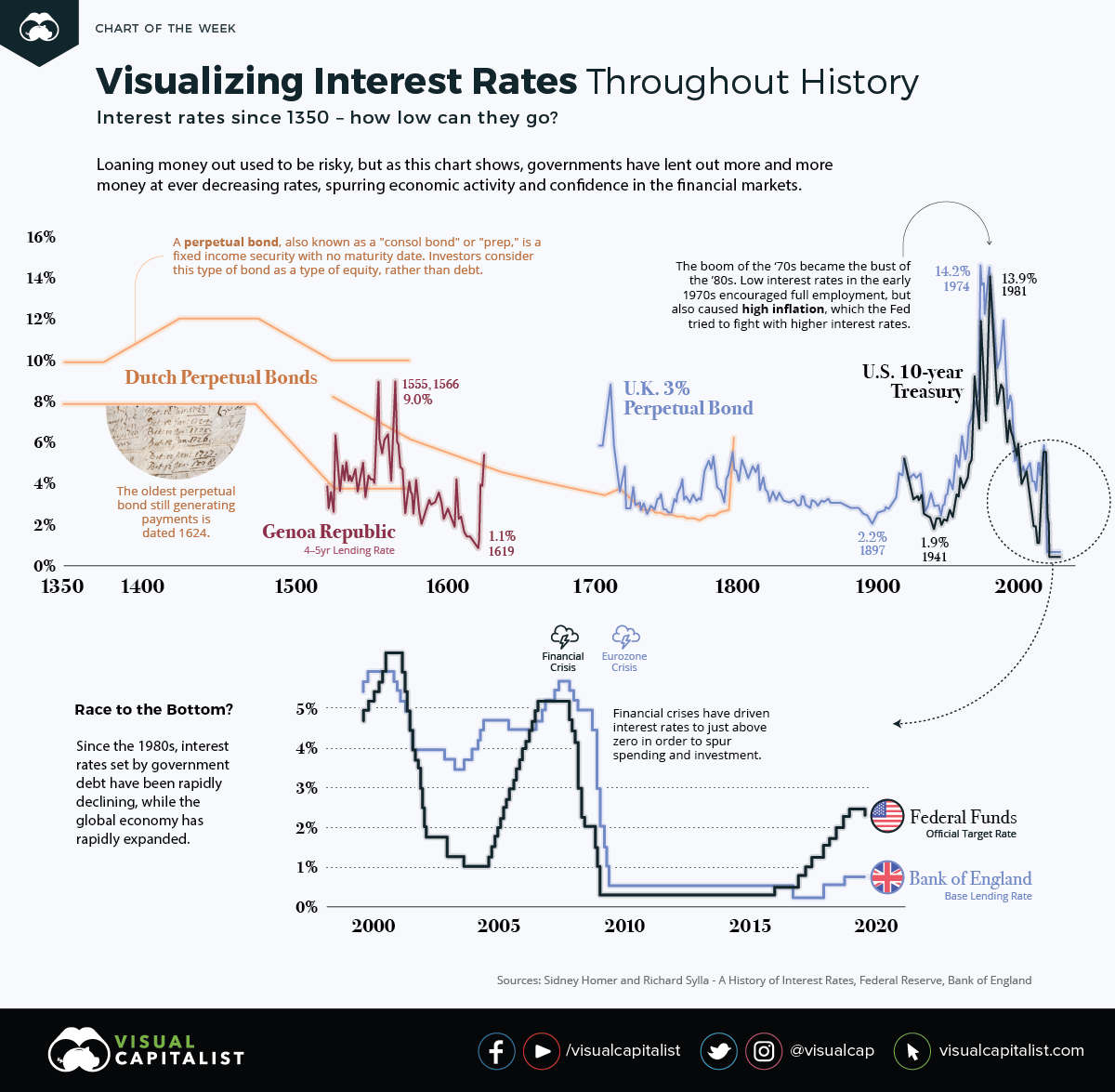

But it pays to remember: very low interest rates are an entirely new phenomenon.

On average, interest rates now sit at their lowest point in 670 years!

Last time interest rates sat anywhere near this low was for a short period of time during the 1600s. When the Genoa Republic provided 4-5 year financing for foreign endeavours by the Spanish Crown.

The average historic interest rate sits around 5-7%.

Now, people do like cheap money. Especially when it’s comparatively cheap.

From about 2000 to 2008, interest rates were much cheaper than they’d been during the past two decades. This fuelled a spending and investment splurge.

Then when they went up again, we had the Global Financial Crisis. Asset prices plunged. The Dow dropped nearly 40%.

And we were thrust into the era of low rates that has persisted ever since.

Until now. When Coronageddon is forcing them even lower.

The problem is twofold.

First, many investors are now worried a real crisis is coming.

‘How can rates be this low? Something must be wrong!’

And the bounce we were expecting in the markets is slow to come through.

Far worse is the dependency created. Especially in the property market.

So, you’ve become an alcoholic…

I’m plying you with cheap beer. You need that to get through the afternoon. Over time, it doesn’t take much to make you stumble. A bad curry. The barmaid showing up to work with a face mask.

Then, all of a sudden, the beer doubles, triples in price. Your alcohol-dependent system cannot take sudden withdrawal. And you end up on the street. With a sign in squiggly letters.

Investors, beware of very low interest rates

First up — there are signs that they’re not working as they used to. Maybe the system is too used to cheap booze.

Second — if there’s any rapid change to them, the money supporting the property market and the share market can quickly dry up.

One of the best things you can do is stress-test your situation.

What if interest rates went up to 9%? Can you afford your mortgage?

What if the share market dropped 25%? Will your portfolio or KiwiSaver get you through?

When investing, the best thing you can do to avoid an interest melt-up scenario is to question the value of anything — everything you buy.

- Is that old wooden home in Mt Eden worth the bid?

- What is the book value and price-to-earnings ratios of the stock you’re buying into?

- How about debt levels?

- Is the earnings growth factored into the price realistic?

- Could earnings get knocked about by COVID-19?

Most importantly, how does the yield look? If that leveraged rental property returns only 3%, it could become quite a liability in a higher interest-rate world.

Stocks with reliable dividends around the 5-8% level might start looking more attractive.

Interest rates will not increase any time soon, will they?

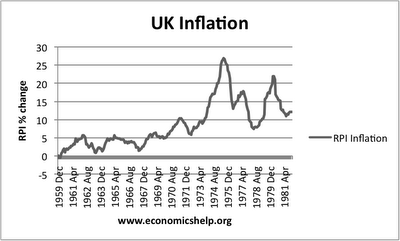

It all depends on inflation these days. At the moment, inflation appears restrained. But when it gets away, it can be hard to keep in check.

We’ve been here before.

Take a look at inflation in Britain through the 1960s. (Other developed countries like New Zealand and Australia followed similar trends).

Interest rates were low back then, too. A version of what we’ve seen through the 2010s.

Then, in the 1970s, there came the shock of the ‘Great Inflation’. A tight employment market led to wage growth getting away. Coupled with an oil shock, inflation became very difficult to contain. And by the 1980s, we had very high interest rates.

New Zealand mortgage rates, 1964-2016. Source: Kiwiblog

The road ahead

Since the 1990s, there’s been a trend of inflation and wage growth kept in check. The manufacturing might of China has been deflating the prices of most consumer goods.

This could turn. We’re reaching near full employment in the US and UK — with labour markets in Australasia requiring immigration to function.

China is being hammered by Trump’s trade pushback. Throwing their ‘developing country’ designation within the World Trade Organization into question. Now the coronavirus has hit their factories.

But there’s a longer-term trend. China is a wealthier country. Ageing fast. The army of younger factory workers is no longer growing.

In this maelstrom, an inflation shock is not impossible. And without cheap factory goods, the addition of an oil shock or even climate change catastrophe could make that happen.

Such environment would need interest rates to crank up quick to try and contain inflation. The property market would face the most acid.

As investors, we need to keep watch for turns. They can happen fast and without warning. So, keep stress-testing both your borrowing and your investing.

Can you survive if the low interest rate cocaine stops?

Can your investment portfolio handle a drawdown of 20% or more?

Look for value. But stay robust.

From memory, that Mt Eden villa passed hands at around 460k. It’s worth three times that now. And even in a perfect storm, could hold above a million.

Robust value, all things considered.

But those were different times.

Regards,

Simon Angelo

Editor, WealthMorning.com

Simon is the Chief Executive Officer and Publisher at Wealth Morning. He has been investing in the markets since he was 17. He recently spent a couple of years working in the hedge-fund industry in Europe. Before this, he owned an award-winning professional-services business and online-learning company in Auckland for 20 years. He has completed the Certificate in Discretionary Investment Management from the Personal Finance Society (UK), has written a bestselling book, and manages global share portfolios.