No crowded cities. No family quibbles.

No money. No private ownership.

And here’s the best part, we put all the smart people in charge.

This is the utopia Thomas More describes in his book by the same title.

Sounds like the ultimate socialist society, doesn’t it?

The higher ups do all the thinking for us. They are the intellectuals after all.

The family structure is destroyed. Families are made up of 10 adults rather than a mother and father. Property and wealth are constantly redistributed to make sure all outcomes are equal.

More also thought there was a place for slavery in his utopian society. Each household had two slaves, most of them were sinners who partook in premarital sex.

I’m not really sure why he thought that was a big no no, as More devalues marriage throughout the book…

Today we have intellectuals like More all over the place.

OK, maybe they’re not as bad as More’s 15th Century thinking.

But they still come up with useless ideas that burden us all.

What you’ve been told is opposite

‘I define intellectuals as persons whose occupations begin and end with ideas,’ economist Thomas Sowell says.

‘I distinguish between intellectuals and other people who may have ideas but whose ideas end up producing some good or service, something that whether it’s working or not working can be determined by third parties.

‘With intellectuals, one of the crucial factors is their work is largely judged by peer consensus, so it doesn’t matter if their ideas work in the real world.’

The world of finance is filled to the brim with these idea-driven intellectuals. One only needs to look at the world of interest rates and banking to see how useless these intellectuals are.

Do you or I understand interest rates and how to push money into an economy?

Of course we don’t. We’re the general public. We don’t have the PhDs and degrees necessary to understand the complexities of the economy.

It’s why we’ve got intellectuals developing models and carefully measuring data points who understand the implications of lowering our raising interest rates.

But as Sowell said, most of these intellectuals are developing ideas that will have no effect at all. The team of economists at central banks are a great example.

They’re all labouring over what interest rates should be. And the mainstream eats it up.

The latest from the Australian Financial Review (AFR):

‘Leading market economists have backed away from predicting higher interest rates in 2019 after Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe retreated from his monetary policy guidance that the next move in interest rates would likely be up.

‘Dr Lowe’s new message that the chances of a rate cut are now evenly balanced with a hike mean the Reserve Bank is more closely aligned with financial markets, which already believed the central bank’s forecasts were too optimistic and are betting rates are going to be lower by Christmas.’

This is nothing but econ word porn.

It’s a distraction to blind you from what’s really happening.

You’ve always been told lower interest rates stimulate growth and higher interest rates lead to lower growth.

But then why is there a positive relationship between economic growth and interest rates?

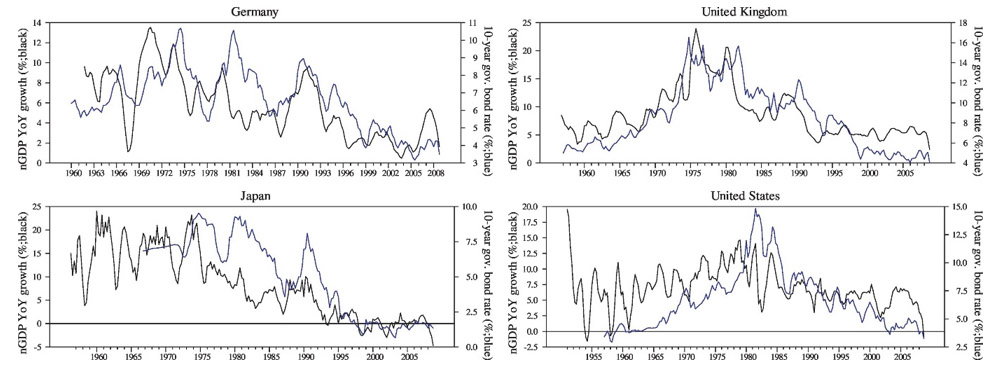

|

| Source: Reconsidering Monetary Policy |

In the graphs above, economic growth (GDP) is the black lines, long-term interest rates (10-year bond rates) is the blue line.

We see the same pattern for short-term rates too.

What does this mean?

It means the age old adage of interest rates spurring growth is not true. If anything the opposite is true. When growth falls or rises, interest rates follow.

You might hear some people say central bankers’ decisions just have a lagging effect, meaning it takes time for lower or higher interest rates to push growth back up or down.

‘The data suggests overall that statistical causality runs from economic growth to long-term interest rates. Nominal GDP growth provides information on future interest rates better than interest rates inform us about future nominal GDP growth,’ economist Richard Werner wrote in his 2000 research paper.

‘Our empirical findings reject the canonical view that interest rates somehow affect economic growth, and in an inverse manner. To the contrary, long-term and short-term interest rates follow the trend of nominal GDP, in the same direction, in all countries examined. This suggests that markets are not in equilibrium and the third factor driving GDP growth is a quantity.’

This makes a whole lot of sense when you just look around the world.

Japan, the Euro Zone, the US…are these rapidly growing economies thanks to low interest rate policies?

No, they’re not.

And it’s because we’re only looking at the price of money (interest rates).

What’s far more important is the actual supply of money. And for the most part that’s out of the central bankers’ hands.

Taxpayers always pay

Earlier this month, I highlighted comments from Westpac Banking Corporation [ASX:WBC] CEO, Brian Hartzer.

He believed banks were not responsible for the Aussie housing slump. I eloquently responded by saying: You are so, Brian!

More recently, CommBank’s chief executive has joined Brian in saying the banks are not to blame. Again, from the AFR:

‘Banks aren’t responsible for any credit crunch and Commonwealth Bank remains willing to lend, its chief executive Matt Comyn says, rejecting notions that the major banks have been knocking back borrowers and cutting loan sizes, triggering the property price correction.’

But then tell me Comyn, who gave homeowners the firing power to outbid each other at auction? Who is granting loans for homeowners to go ahead and purchase that second home?

Maybe there is some loan fairy I’m not aware of…

This is the far more important role, more important than central banks setting the price of money. And it’s played by the commercial banks.

They create the supply of money in the form of home loans, business loans and lending in general.

This money creation is what grows economies. But it can also lead to asset inflation and create bubbles.

It all depends on what activities the banks create money for.

If they create money for value-added activities, loans to produce new goods and services, then the economy grows.

If they create money for consumption and speculation, like home loans or stock market purchases, you get inflation and possibly an asset bubble.

The worst part is the intellectuals over at the central bank refuse to acknowledge this. They also refuse to take blame when it was they who perpetuated crises.

Cast your mind back to the eve of the 2008 meltdown.

What was the cause?

Almost everyone will tell you it was central bankers and their prolonged lower interest rates.

That is somewhat correct — central banks, like the US Federal Reserve, were handing out free money. But they weren’t handing this money to the public. They were handing it out to the banks.

The idea was to flush the banking system with cash and for the banks to create more money in the economy for value-added activities.

What they did instead was lend for consumption and speculation, while speculating on securities themselves.

The most frustrating thing about 2008 is who would end up paying in the end.

If the Fed wanted to, they could’ve bought up all the bad loans and assets from the banking sector. It would have cleaned up balance sheets and cost the Fed nothing (they can print money for free).

But who ended up paying?

The taxpayer!

The US taxpayer bailed out the banks for their ‘profit by any means’ behaviour. And I repeat, the Fed could have done this at no cost.

Yeah, those intellectuals really know what they’re doing…

What happens now?

For those of you not in complete despair, might I suggest something…

Forget interest rates.

Don’t bother listening to central bankers or commentary on what interest rates will do next.

It’s just a bunch of intellectuals throwing ideas around that will have little to no effect.

The markets might move initially on this stuff. But now, you know better.

If you want to look at anything, look at money creation.

The supply of money is what grows an economy or inflates asset prices.

The intellectuals won’t tell you that because they’d soon be out of the job.

Your realist friend,

Harje Ronngard

Harje Ronngard is one of the editors at Money Morning New Zealand. With an academic background in finance and investments, Harje knows how difficult investing is. He has worked with a range of assets classes, from futures to equities. But he’s found his niche in equity valuation. There are two questions Harje likes to ask of any investment. What is it worth? And how much does it cost? These two questions alone open up a world of investment opportunities which Harje shares with Money Morning New Zealand readers.