Today, we wrap up this three-part series on the Silk Road.

First, we covered the ancient Silk Road, Zhang Qian’s explorations, silk, and the Pax Romana.

Yesterday, we discussed how two Byzantine monks stole silkworm eggs. Then how the Mongol Empire thrived on the Silk Road’s commerce. Lastly, how it led to the Black Death.

Now we get to the meat of the issue — the modern Silk Road.

You won’t see any camels or caravans.

No, today you’ll find Camel cigarettes, cars and vans.

You’ll see steel freight containers on trucks, trains and cargo ships. Millions of them. About 33 million in fact.

The routes are new, but if you strip away the tarmac and rail tracks, you’ll notice that the stones of the ancient Silk Road lie at the foundation.

I’m talking about contemporary merchants following the same corridors as their predecessors. Through the Bay of Bengal and the Arab Sea. Across the central steppes. And instead of villages along the way, there are now power plants, seaports, airports, and more…

All to make it easier for the Chinese to trade with Europe, Asia, and Africa.

Déjà vu

As a refresher, none of this is new. It’s happened before. The same players. The same goals.

During the Han and the Tang dynasties, China developed a two-pronged trade strategy across land and sea. They capitalised on war-torn nations in the Middle East to help reach the wealth in Europe.

They sold Chinese goods in return for the West’s gold and military technology.

But this time, the Western capital isn’t Damascus or Rome. It’s Brussels — the headquarters of the European Union.

And there isn’t an emperor in China any more…there’s President Xi Jinping.

And he’s going to attempt to outdo what his ancestors achieved.

A modern Silk Road.

Maybe that means prosperity throughout the regions, as the ancient Road provided.

Or maybe it is something more sinister.

Either way, it’s happening.

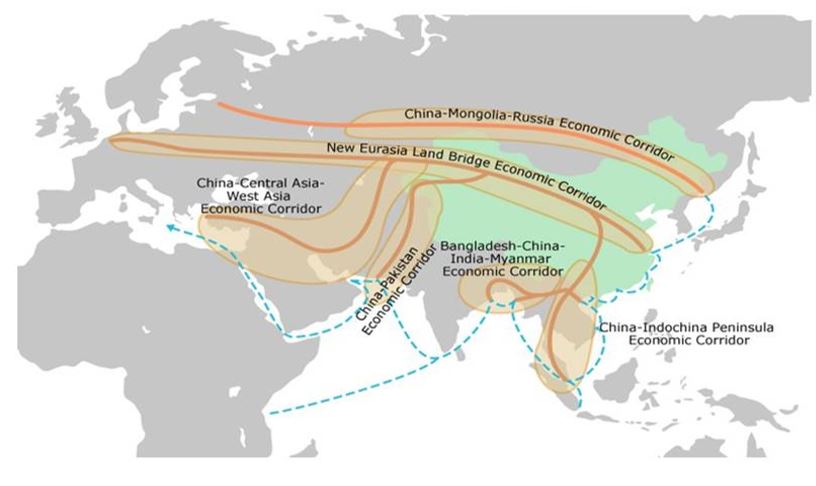

President Xi Jinping calls his ‘project of the century’ the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The ‘Belt’ refers to the land route through the Middle East all the way to the Black Sea.

There will be not one road, but several…each taking a different corridor through different countries. The paths will skirt along the Caspian Sea and arrive in terminals like the Balkans, the Arabian Peninsula, the West Bank, and the former USSR.

It targets vulnerable countries. Countries that are the black sheep of the world. Countries that are more than happy to accept Chinese funds with few questions asked.

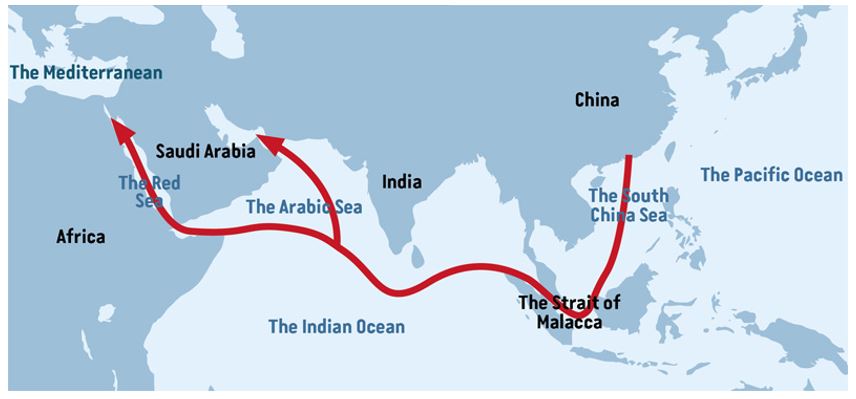

The ‘Road’ covers the sea route. It starts in the Yellow Sea near China’s mega-port-city, Tianjin. It bounces along the East China Sea, the South China Sea to the Strait of Malacca.

From there it follows the old sea route through the Indian Ocean to the Horn of Africa and the Arabian Sea.

When combined, the ‘Belt’ and ‘Road’ mirror the same economic tactic that the ancient Hans followed.

But there’s a big difference. I’ll explain it in a moment.

First, let’s dig deeper into the two branches of the BRI.

The Belt

The Belt represents the land branch of the new Silk Road. It’s comprised of corridors that stretch from China’s eastern coast across the continent.

|

Source: Lehman Brown |

Moving cargo over land can be difficult and cumbersome. That’s where the Belt comes in. It addresses infrastructure deficiencies and streamlines transportation.

The Chinese have offered to help by loaning large amounts of cash to these countries for infrastructure projects such as:

- Highways

- Bridges

- Railways

- Power plants

It bolsters the local economy and provides China with a reliable platform for transporting goods.

But there’s a catch…

Many of the loans are far beyond what these countries can afford. The Chinese know that. They don’t expect the money back.

When the countries fail to repay the loans, they elect to pay China back by giving them control over the assets.

Take the Pakistani port of Gwadar for example. The Chinese poured about $1.5 billion into developing a deep-water port on the site. In return for the investment, the Pakistani government handed over full control of the port to the Chinese. And they made the area a special tax-free economic zone.

In other words, China is ‘buying’ outposts along the Belt to ease the transport of goods. [openx slug=inpost]

The Road

On water, the Chinese are placing stepping stones that will ease their maritime commerce. They call this sea route the ‘Road’.

|

Source: Bunkerist |

Along the Road, outposts like Gwadar will offer Chinese ships strategic anchor points.

These outposts aren’t only for economic purposes; many of the ports are overtly military.

This is China’s ‘String of Pearls’ strategy.

It’s the idea that a ‘string’ of naval bases along the northern Indian Ocean will guarantee Chinese dominance over the sea. And lead to dominance over the whole of Asia.

So, picture it — a queue of Chinese cargo ships sailing westbound along the entire southern Asian coast. On their flanks, Chinese destroyers guiding and protecting. With the ‘pearls’ providing safe haven along the way.

China would own the seas.

The new global hegemon

Make no mistake — this is a full-on campaign for economic and political dominance.

Hidden behind the thin veil of infrastructure projects lies a Chinese master plan, centuries in the making.

It’s one that could dethrone the West.

And it’s happening now.

Western leaders are fearful. France’s president, Emmanuel Macron, warned that the BRI ‘cannot be the roads of a new hegemony that will make the countries they traverse into vassal states. The ancient silk roads were never purely Chinese…These roads are to be shared and they cannot be one-way.’

American defence secretary, James Mattis stated that ‘No one nation should put itself into a position of dictating [the BRI].’

Joe Kaeser, CEO of Siemens, said, ‘China’s [BRI] will be the new World Trade Organization – whether we like it or not.’

President Xi Jinping was quick to deny:

‘China will not engage in geopolitical games for selfish ends, nor will it create an exclusive club, nor will it force trade deals on others from above.’

But the evidence is there. The Belt. The Road. The String of Pearls. They all point to back to one thing — Beijing.

So, what do we do?

For now, we can only observe and report. The pieces are in place. The campaign is underway.

We’ll keep a careful eye on the development on China’s new Silk Road and report the details to you.

Best,

Taylor Kee

Editor, Money Morning New Zealand

Taylor Kee is the lead Editor at Money Morning NZ. With a background in the financial publishing industry, Taylor knows how simple, yet difficult investing can be. He has worked with a range of assets classes, and with some of the world’s most thought-provoking financial writers, including Bill Bonner, Dan Denning, Doug Casey, and more. But he’s found his niche in macroeconomics and the excitement of technology investments. And Taylor is looking forward to the opportunity to share his thoughts on where New Zealand’s economy is going next and the opportunities it presents. Taylor shares these ideas with Money Morning NZ readers each day.