Have you heard? There’s been a lot of buzz lately about Warren Buffett’s cash pile.

The reported amount is $334 billion.

That sounds like a big sum, doesn’t it?

Gigantic? Colossal? Huge?

Source: Image by Paul ( PWLPL) from Pixabay

Well, here’s the thing. $334 billion may sound big on its own terms. But, really, this is just one slice of a larger pie, which is worth $1.153 trillion:

- Yes, that’s right. According to the latest reported figures, Berkshire Hathaway has a total asset base of $1.153 trillion. This covers a wide swathe of shareholdings and business interests.

- So, what happens if we take Buffett’s cash pile, then divide by Berkshire’s total asset base? What do we get? Well, we get 29%.

- To borrow a mythical phrase from Sherlock Holmes: ‘Elementary, my dear Watson.’

So, Warren Buffett is holding 29% in cash. This means that the remaining 71% will still be invested in productive assets. Is this percentage split significant? Yes? No? Maybe?

- Well, if you’re a pessimist, you might be inclined to believe that Buffett is holding all that cash because the market is going to crash soon.

- However, is this a fair call to make? Or…is this just shallow reasoning? Well, in order to understand Buffett’s mindset, we first have to understand what exactly a market crash is supposed to look like.

Over the past 100 years, there have only been four instances where the American market has suffered a decline of 10% or more in a single week. I’ll list these events here:

- October 1929.

- October 1987.

- October 2008.

- March 2020.

Now, for the sake of clarity, what happens if we take these four events, add them together, then divide them by 100?

- Well, what we get is a fascinating result. Over the past 100 years, the odds of a crash happening in any given year was only 4%. Shockingly small.

- This seems to suggest that market crashes (in the true sense of the word) are much rarer than you might think.

So, why do people stress themselves out so much? Why all the anxiety? Why all the hoopla?

- Well, maybe the problem here is one of perception. I find that people will often confuse gentle corrections (which are historically common) with sudden crashes (which are historically uncommon).

- Perhaps there’s an element of media manipulation here. I’ve noticed that journalists have a habit of using the word ‘crash’ repeatedly. They will apply the term to anything and everything. But this is misleading clickbait, isn’t it?

- For example, not every economic recession can be called an economic depression. Therefore, not every market correction can be called a market crash.

- Using the wrong label is inaccurate at best; ignorant at worst. Perhaps this is a case of the blind leading the blind? Perhaps we should be cautious of being led astray by misguided prophets?

Just last week, I came across an interesting comment by US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent. He used to be a hedge-fund manager before he took up his government role. He was asked about the recent burst of market volatility in March. Was there anything for investors to worry about? Well, here’s Bessent’s response:

I’ve been in the investment business for 35 years, and I can tell you that corrections are healthy, they are normal. I’m not worried about the markets. Over the long term, if we put good tax policy in place, deregulation and energy security, the markets will do great.

Bessent appears to be as cool as a tall glass of water. So, is he right about the behaviour of the American market? Or is he being too relaxed about the risks? Too dismissive?

- Well, historically speaking, the numbers actually seem to be on Bessent’s side.

- Yes, corrections are regular. Yes, they happen all the time. Yes, they are normal.

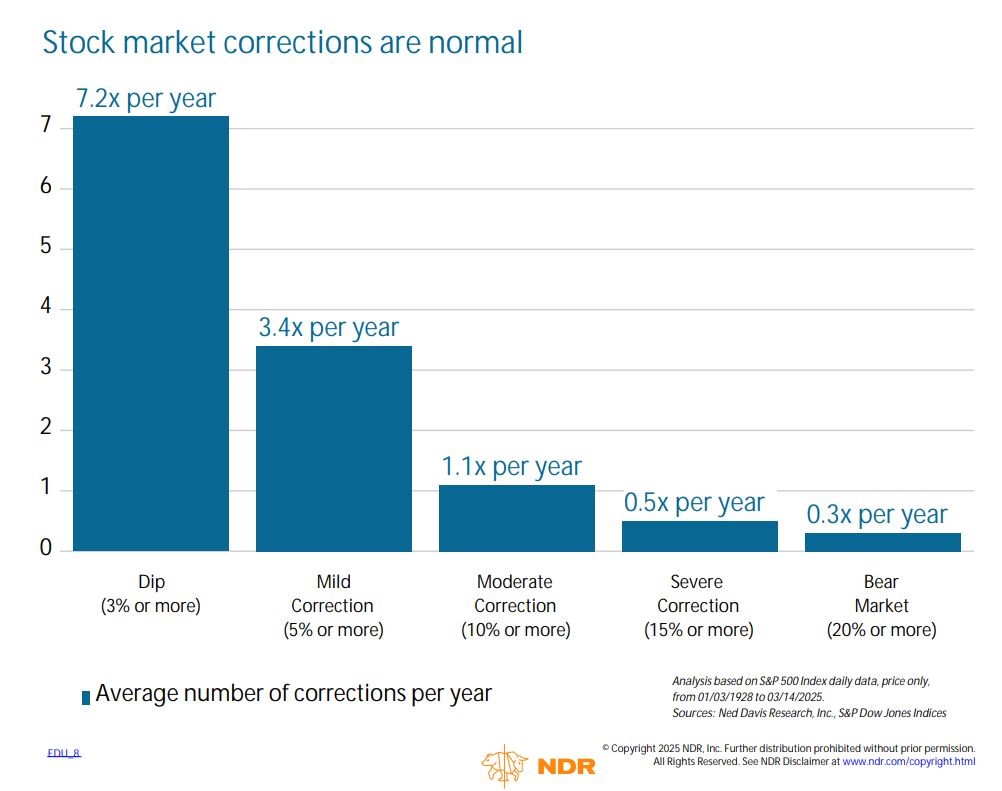

Source: Brian Salcetti / LinkedIn

If we choose to dig deeper, we can uncover some interesting data here. Since 1928, corrections have happened every year on the American market:

- In fact, mild corrections of at least 5% tend to happen three times a year, on average. However, most of these sell-offs are fleeting. They’re like blips on the radar. Blink and you might miss them.

- How come? Well, I suspect that these corrections go unnoticed because the media simply fails to report about them. Hence the lack of awareness.

- As the old saying goes: ‘If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?’

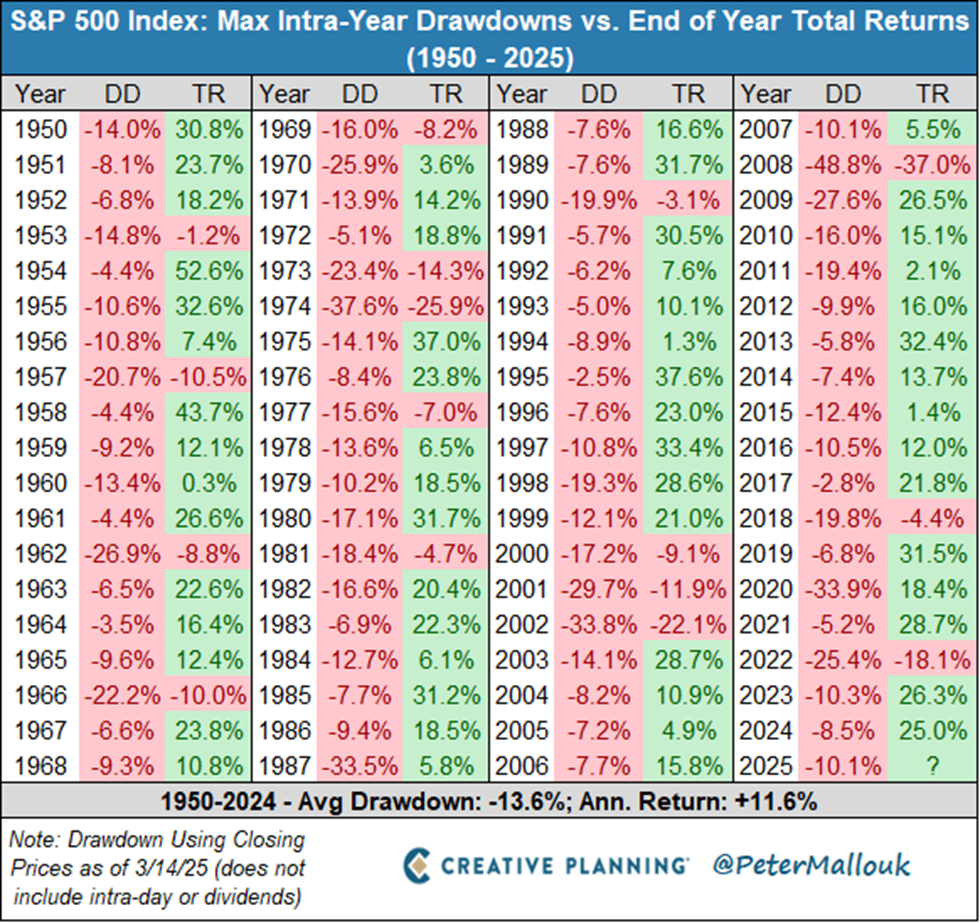

Source: Peter Mallouk / X

Now, if we choose to dig even deeper, we can find more interesting data. Here’s how the American market has behaved over the past 75 years:

- Yes, there have been dips and corrections happening every year. Yes, drawdowns in the 12-month period between January and December are common. They’re so common, in fact, that there has never been a year where the colour red didn’t show up.

- However, here’s the twist. Despite all the red, the market still ends up in the green at the end of most years. This has happened 79% of the time. The win ratio is pretty strong.

Now, what is extraordinary here is that this win ratio also happened during two spectacular market crashes (October 1987 and March 2020):

- In both instances, the American market declined over 10% in a single week. Oh yeah. That was scary as hell. Investors experienced heavy drawdowns into the red. No doubt, these experiences were made more frightening by the breakneck speed of the declines.

- And yet…by the end of both years…the market had bounced back into the green. Indeed, the market showed incredible resilience. Powering forward. Defying the doomsayers.

This is why it’s so hard to time the market, isn’t it?

- When the fear is being elevated, when the headlines are screaming, it can be hard for any investor to remain rational.

- In that moment of moments, it seems like everyone loses their minds. Everyone wants to sell out. This happens even if the fear is fleeting and ultimately turns out to be a blip on the radar.

- Napoleon Bonaparte, the great French conqueror, had a fascinating observation about such herd behaviour. When dealing with such upheaval, Napoleon’s definition of a genius was this: ‘The man who can do the average thing when all those around him are going crazy.’

Yes, indeed. So, let’s circle back to Warren Buffett, shall we?

- I have scrutinised everything Buffett has said over the years.

- Not once has he ever made any predictions about a market crash.

- Not once has he advised anyone to time the market.

- On the contrary, what Buffett usually talks about is about finding value and capturing value. Just common sense, really.

In fact, you’ll find Buffett’s folksy wisdom in clear evidence on February 22. Here’s what he said to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders in his latest annual letter:

Despite what some commentators currently view as an extraordinary cash position at Berkshire, the great majority of your money remains in equities. That preference won’t change.

Yes, Buffett remains committed to productive assets. Yes, he will stay invested in productive assets. However, if you read in between the lines, you will understand the role that cash plays in the Berkshire portfolio:

- Cash here acts as a shock absorber. A defensive cushion. A provider of psychological comfort.

- This means that Buffett will never be forced to sell out of his productive assets at an inconvenient time. He can continue to hold on to these assets, regardless of what happens in the market. Freedom and flexibility is great.

Yes, I’m well aware that alarmists will look at Buffett’s cash position and say, ‘This is proof that you need to sell all your stocks now. Go completely into cash immediately.’

- But wait. Hold on. That’s not what Buffett’s strategy means at all. What it actually means is that Buffett has decided that 29% cash is the optimum cushion for Berkshire Hathaway. Full stop.

- To say that Buffett is preparing for the mother of all crashes is perhaps a stretch of the imagination. It’s actually fairer to say that Buffett is maintaining a moderately defensive posture for any and all corrections that will occur. (You must remember: mild corrections of at least 5% will happen three times a year, on average.)

- Therefore, holding some cash gives Buffett two options: he can hold on to his existing positions without feeling any pressure, and he can choose buy more if he sees value.

- Either way, Buffett understands that it’s better to have the majority of his equity invested in productive assets. He can have his cake and eat it too.

Regards,

John Ling

Analyst, Wealth Morning

(This article is the author’s personal opinion and commentary only. It is general in nature and should not be construed as any financial or investment advice. Wealth Morning offers Managed Account Services for Wholesale or Eligible investors as defined in the Financial Markets Conduct Act 2013.)

John is the Chief Investment Officer at Wealth Morning. His responsibilities include trading, client service, and compliance. He is an experienced investor and portfolio manager, trading both on his own account and assisting with high net-worth clients. In addition to contributing financial and geopolitical articles to this site, John is a bestselling author in his own right. His international thrillers have appeared on the USA Today and Amazon bestseller lists.