The cost-of-living crisis bites most hard in those areas you can’t avoid.

Here in New Zealand, home insurance premiums increased 24.6% in the year to March. Contents insurance 28%.

A World Vision survey found the cost of a basket of common foods increased 56% from February 2023 to 2024.

I was speaking with a friend who moved here from the UK. He was complaining:

‘You have your pay. Then all the bills come in. And there’s just nothing left in New Zealand.’

When I considered his situation, I realised he’d been insulated for a time, then arrived here at the peak of the inflationary predicament.

In fact, what we’ve been witnessing is a worldwide phenomenon.

People feel the government has lost control of the financial system. It’s a struggle to make ends meet, let alone get ahead. The ballast of the middle class is crumbling. History shows us as far back as the Roman Empire that widening inequality can lead to instability.

We know how we got here.

Iatrogenic economics

Iatrogenesis is a medical term. It occurs when the imposition of a treatment causes adverse effects or harm. For example, the amputation of the wrong limb. Or side effects from prescription drugs that damage the brain.

More recently, it has been used to describe a range of scenarios where an intended fix causes widespread pain. Nassim Nicholas Taleb expands this in his book Antifragile: Things that Gain from Disorder.

Government response to the Covid-19 pandemic, particularly here in New Zealand, appears to have been economically iatrogenic.

Lengthy and repeat lockdowns (including for a single case) meant spending needed to increase drastically to support people.

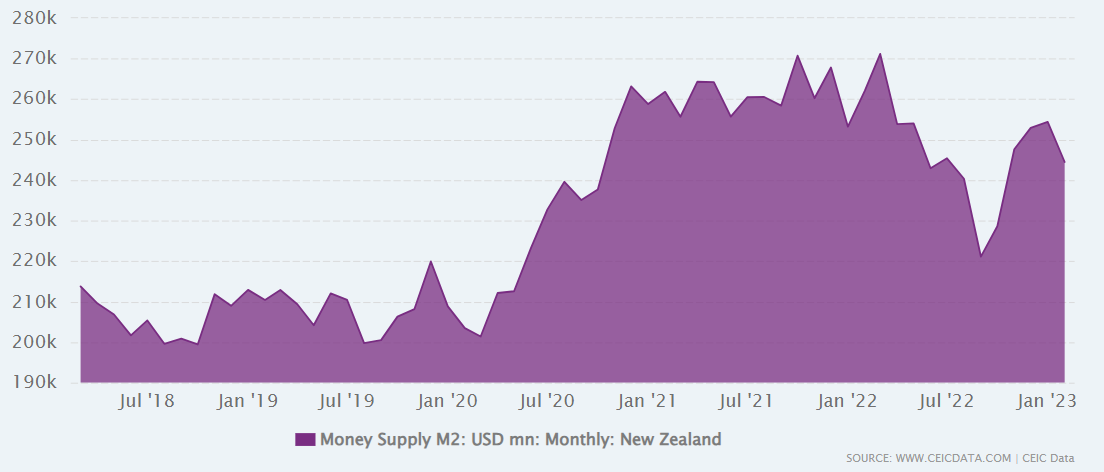

The result was that between 2020 and 2021, New Zealand’s money supply increased by about 35%.

Was this the fault of monetary policy?

Today’s economy is a credit-based one. Central banks can loosen or tighten the money tap as needed. This need is often driven by government policy.

Of course, a credit-based economy is flexible. Boom-and-bust cycles can be lessened by interest-rate settings.

Going back a century, this option did not really exist. Major currencies like the US dollar were fixed to the price of gold — with other currencies being fixed to these.

When this is mentioned, there’s often a cry that we should go back to the gold standard. It had its merits, but we should also remember The Great Depression. There were few easy ways to loosen the economy when it froze. The impacts lasted years and were devastating. These conditions helped give rise to the Second World War.

As for the cost-of-living crisis today — if the Reserve Bank allowed the money supply to increase 35% by 2021, causing obvious inflation, aren’t they to blame?

They have one main tap: monetary settings via the OCR, and sometimes via money market intervention. The point is they respond to government policy. Lags and the difficulty of forecasting mean they tend to undershoot or overshoot.

Previous, they were hamstrung by a triumvirate mandate covering not only price stability (a 0-3% inflation target), but also maximum sustainable employment and sustainable home prices.

Governments and inflation

In my view, the last New Zealand government (before October 2023) was out of control. The individuals involved had domain-specific experience in academic subjects such as political science. Very little of it could be translated into economic management.

The pandemic seemed to provide cover or ingrain habit for a massive increase in the public service and government spending. By 2023, it had reached 65,699 FTEs — an increase of 83% since 2012, and far ahead of the population increase of 20%.

This increase did not seem to improve vital services as the bulk of the increase did not go to frontline doctors, teachers, or police. Rather, it seemed to boost unelected bureaucrats and ideologues spinning rolls of red tape or cultural Marxism, making the life of everyone else more difficult. And, of course, more costly.

As the largest spender in the economy — 33% of GDP by 2024 — the government has the largest bearing on inflation.

Yes, while some of their number cycled the pavements in vegan sandals plotting ‘complex new initiatives’, or took hypocritical business-class carbon space to their next conference, we paid the price as mortgages soared and asset values slid.

Don’t Cry for Me Argentina

Argentine National Congress, Buenos Aires, Argentina. Source: Boris G / Flickr

This South American country provides a fascinating study.

In the 1950s, its per capita income was about that of Western Europe. These days, it is below Romania’s, with more than 57% of Argentina’s population living below the poverty line.

For years, it has struggled with hyperinflation and a public service out of control.

This changed last year with the election of firebrand economist Javier Milei.

With deep cuts to the public service and stringent spending cuts, they have managed to slash inflation to record lows and restore hope in an economic future for younger people.

When you trim the bloat and cronyism of an unwieldy state, the most significant driver of inflation gets cut. The central bank is then able to slash the benchmark interest rate — which in Argentina they’ve already cut to date by more than 20% to 40%.

In the New Zealand context, I see the same risks of bureaucratic flab and rot constricting the blood supply of this economy.

It was telling that, in the last election, Wellington was strongly left-leaning. It is also telling that the centre of gravity for income inequality has shifted. Those on higher incomes may quite likely be left-leaning elites on the taxpayers’ cheque.

For example, two of the most left-leaning electorates in the country (Wellington Central and Rongotai) have levels of people on higher incomes that are up to 60% more than the rest of the country.

We are in for pain

Eliminating inflation is not easy.

Monetary policy can have a lag of over 18 months. In New Zealand, a typical fixed mortgage is for two years. This month, the average mortgage rate reached about 85% of the Reserve Bank’s estimated peak of 6.5%.

The new government is working to reduce spending, with over 4,550 public service job cuts to date. It is telling that I’ve not found anyone who has noticed a material reduction in essential services.

Tax cuts have also been promised. These are unlikely to be inflationary. When you cut taxes strategically, you incentivise more people to work and businesses to increase their production. This has a disinflationary effect as supply of goods and services increase.

Investors and optionality

Optionality means you aren’t reliant on one situation or market to generate wealth. You have options.

If you’re about to be made redundant with your only investment being a rental property that doesn’t pay its way, your optionality is low.

If you’ve built multiple income sources and have exposure to growth in larger economies such as the US, Europe, or even Australia, your optionality is high.

A crisis, especially a cost-of-living crisis, will give those with optionality more opportunity.

As I write, the European Central Bank looks set to lower interest rates soon.

Yet many dividend-paying companies with significant real estate sit at value on European stock exchanges.

At Wealth Morning, we run a night trading desk. We focus on building up robust and profitable portfolios for our Eligible and Wholesale clients.

We seek to tackle the inflation crisis head on.

By exploiting it with optionality.

Regards,

Simon Angelo

Editor, Wealth Morning

(This article is the author’s personal opinion and commentary only. It is general in nature and should not be construed as any financial or investment advice. Wealth Morning offers Managed Account Services for Wholesale or Eligible investors as defined in the Financial Markets Conduct Act 2013.)

Simon is the Chief Executive Officer and Publisher at Wealth Morning. He has been investing in the markets since he was 17. He recently spent a couple of years working in the hedge-fund industry in Europe. Before this, he owned an award-winning professional-services business and online-learning company in Auckland for 20 years. He has completed the Certificate in Discretionary Investment Management from the Personal Finance Society (UK), has written a bestselling book, and manages global share portfolios.