Warlords. Communists. Nationalists.

China was a fractured nation in the late 1800s and early 1900s. The land was being fought over by various groups with competing agendas. Starvation, disease, and murder was rampant.

Western observers could only shake their heads as they watched the chaos unfold, calling China ‘the sick man of Asia.’

It was a fitting name for a seemingly hopeless country.

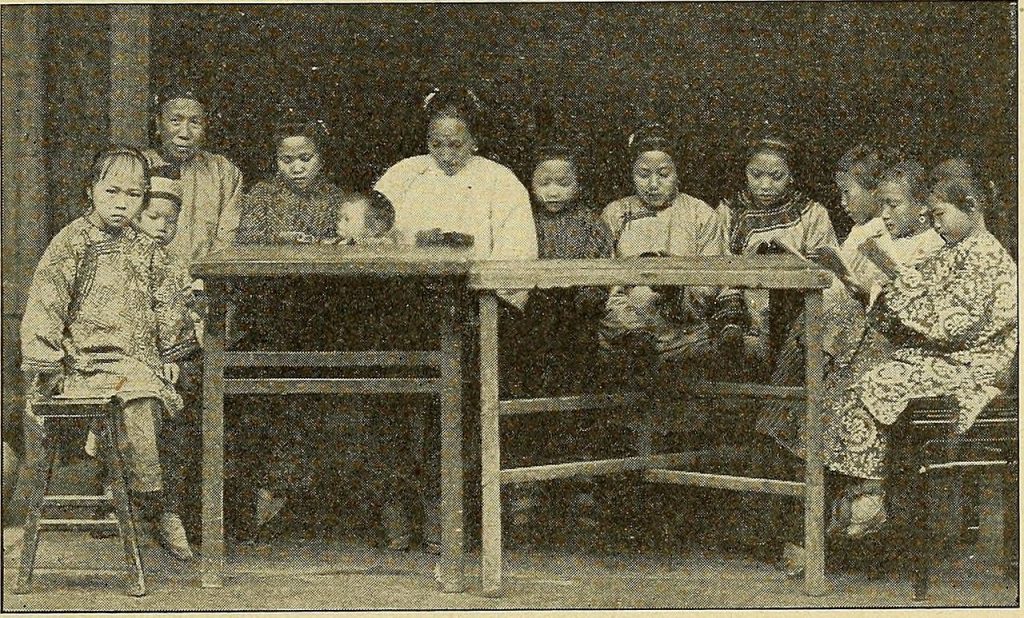

Fuzhou women and children studying the Bible, circa 1870s. Source: Wikipedia

Among the many who suffered during this turbulent time were my great-grandparents:

- They were of Fuzhou descent and lived in Fujian, a coastal province on China’s south-east.

- The rising violence and nosediving economy gave them much to worry about.

- How bad was the civil war going to get? Could they afford to put food on the table? Who would be the next poor soul in the village to die?

- These were all terrible questions to contemplate.

Fortunately for my great-grandparents, there was a way out:

- Western traders had long used Fujian as a base to spread Christianity and secure business opportunities.

- The British, in particular, were ardent recruiters — they encouraged the local Chinese to emigrate to Southeast Asia to work in rubber plantations and tin mines.

- ‘A better life for you. A better life for your children.’

- This was a message of salvation that was impossible to ignore.

Leaving China forever

Nervous but hopeful, my great-grandparents took heed:

- They boarded rickety boats that were packed with a heaving mass of humanity, and they departed their homeland.

Pathway of Chinese migration. Source: Wikipedia

Their voyage through the South China Sea was perilous:

- They were exposed to the elements, the wooden hulls of their vessels creaking and groaning from every incoming wave.

- Food was scarce, leaving them malnourished.

- Worst of all, they also risked being intercepted on the open sea by pirates, who were just waiting to pillage and murder and rape.

- What a harrowing journey that must have been. How vulnerable they must have felt.

Fortunately, against the odds, my great-grandparents arrived safely on the rugged shores of British Malaya:

- They disembarked, staggering down the pier, the crushing flotsam of migrants streaming around them.

- There was no red-carpet welcome waiting. Just the harsh reality of being dirt-poor and trying to start a new life amidst the humid climate and tropical terrain.

Chinese worker tapping rubber in British Malaya. Source: Al-Jazeera

Still, my great-grandparents counted their blessings:

- The food in Malaya was reasonably abundant, and the British colonials were nowhere near as cruel as the Chinese warlords back in the old country.

- All things considered, Malaya felt like a land that was good enough for them to set down roots in. Perhaps for the next few generations. Until something more hopeful came along.

You could say that all this has become the founding mythology of my family:

- A story of exile. Heartbreak. Resettlement. And working really hard to try to hold on to something tangible, something solid, despite all the uncertainty that this mad world sees fit to throw at you.

Passing the torch

I’m a fourth-generation Malaysian of Chinese Fuzhou descent. I also happen to be a first-generation New Zealander. I was raised a Christian. I grew up speaking only English at home:

- There are millions like me. An ethnic diaspora.

- We celebrate Christian tradition just as easily as we celebrate Chinese New Year.

- We enjoy a good English roast just as much as we enjoy a good Asian stir-fry.

- We love Cantonese soap operas just as much as we love Home & Away, Shortland Street, and Grey’s Anatomy.

Celebrating Christmas. Source: Canva

We straddle the razor’s edge between East and West:

- We have always been there. Quiet, low-profile, and unassuming. And today, we find ourselves caught within the power plays of a turbulent 21st century.

Chinese communities across the world

In Malaysia, we are under attack by Malay ultranationalists with a postcolonial score to settle:

- At various times, they have accused us of being pro-China, pro-Western, pro-Zionist.

- The exact accusation always changes, depending on which way the wind blows. But one thing is clear: we are always regarded as eternal outsiders.

In Singapore, we are mindful that we are an ethnic Chinese island fishing in a hostile Malay sea:

- We are a tiny city-state with no natural resources. Our only competitive advantage is our highly skilled population, and so long as we can maintain it, the most advanced military force in Southeast Asia.

- A Latin phrase sums up our fragile existence. Si vis pacem, para bellum. If you want peace, prepare for war.

In Indonesia, we only make up around 1% of the population:

- An insignificant speck in the grand scheme of things. Yet various campaigns of genocide have forced us to adopt Indonesian names and Indonesian customs.

- We hide our Chinese identity — always fearful that the next racial riot is just around the corner. To survive and pass on our heritage under such terrible circumstances may well be the greatest accomplishment of all.

Protests in Hong Kong. Source: The New York Times

In Hong Kong, we were promised ‘one country, two systems’:

- But it’s a shattered dream now. Mainland China is taking steps to forcibly change and shape our cultural reality.

- Cantonese, our main lingua franca, is being replaced by Mandarin. Our democratic institutions have been dismantled. Anyone who protests is labelled as a British or American agitator and locked up. The future doesn’t look happy.

In Taiwan, our legitimacy as a nation is a fraught subject:

- We are isolated from the global community, facing intimidation from the Goliath just next door.

- Despite this challenge, we have succeeded and prospered anyway — because what other choice is there?

Finally, throughout the Western world, our immigrant communities continue to thrive:

- We pay our taxes. We obey local laws. We teach our children to study hard, work hard, and never depend on social welfare.

- But the hostility from the nativist population sometimes flares up during times of economic unrest. Whenever that happens, we do what our parents tell us to do: just bite our tongue and keep our heads low. It’s better that way.

- We are here because we believe that Western democracy is better than the Eastern authoritarianism that we left behind. Yet we are keenly aware that better doesn’t mean perfect. So we don’t complain. We just make our peace with it.

Millions of lives. Millions of stories. Each one unique and remarkable:

- The Chinese diaspora offers a rich cultural fabric. A diverse narrative that goes beyond the headlines about China and communism and trade wars.

- We are so much more than just the stereotype of where we originally came from. Our story is one of family, faith, and resilience — despite the turbulence that we have endured across borders.

- What keeps us going? The belief that somehow — maybe — tomorrow will be better. And if not tomorrow, maybe next year. And if not, maybe even the next generation.

- Sometimes all you need is forward-looking optimism.

It’s time to have your say

I hope that you’ve enjoyed reading our articles as much as we’ve enjoyed writing them.

By the way, I have a small favour to ask:

- Would you like to write a review of our work here at Wealth Morning?

- Do you want to let us know if our stories have inspired you in a positive way?

- Do you want to let us know if our stories have helped you become a more successful investor?

We truly value your feedback.

It encourages us. It helps us to do better. It helps us to reach further.

So, if you’d like to leave us a review, it’s quick and easy. It will only take two minutes of your time:

❤️ Please click here to review us now on Trustpilot.

Thank you so much in advance for your kindness and generosity.

Your readership keeps us going!

Regards,

John Ling

Analyst, Wealth Morning

John is the Chief Investment Officer at Wealth Morning. His responsibilities include trading, client service, and compliance. He is an experienced investor and portfolio manager, trading both on his own account and assisting with high net-worth clients. In addition to contributing financial and geopolitical articles to this site, John is a bestselling author in his own right. His international thrillers have appeared on the USA Today and Amazon bestseller lists.