There’s a crime wave sweeping the developed world. It’s been going on since the pandemic.

New Zealand is leading the pack, with violent crime in Auckland up 30% last year.

The most shocking aspect has been the age and approach of newcomers. Ram-raiders from the age of 11.

No climbing trees or The Adventures of Tintin for these kids. They’re behind the wheels of stolen cars, smashing through shopfronts.

Some say the ideological culling of the prison population is to blame. Others the decline of family and social values. In particular, the erosion of Judeo-Christian underpinnings.

From a longer perspective, that is correct. There is a lack of thought behind actions and choices. No appetite to run Pascal’s wager over life and faith decisions.

Yet immediate triggers for deprivation and crime may be seen in the abuse of finance.

Queen Street’s Maori wardens identified the problem when speaking to The Guardian last year:

The crime wave we’re seeing is the symptom of ‘a set of social problems that New Zealand has struggled to make progress on: housing affordability, inequality and the rising cost of living.’

Maori wardens are the eyes and ears of a city seeing hardship. As Blaine Hoete, a Maori warden in Auckland, put it: ‘We need to remove the financial stress within the homes.’

Worsening financial stress comes down to one force. One silent thief: inflation has been running hot.

It’s not like there aren’t any burning lessons from the past.

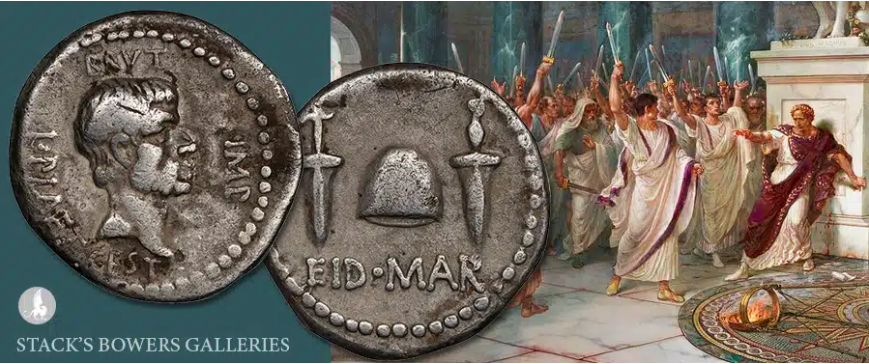

The Roman Empire fell on hyperinflation

Denarius of Brutus. Source: Coin Week

The rot began to set in at the end of the 2nd century AD:

- Inheritance taxes were used to raise the pay of the key instruments of the State. Soldiers, for example, saw a 50% pay increase.

- Almost any inhabitant of the empire was admitted to Roman citizenship to expand the tax base. ‘Immigration’ was not well-considered or checked.

- The basic coinage — the silver denarius — had been introduced by Augustus at the end of the 1st century BC at about 95% silver.

- By the age of Marcus Aurelius, in 180 AD, that was down to 75% silver.

- In the time of Caracella, around 211 AD, the ‘silver denarius’ had fallen to just 50% silver.

- To cope with rampant inflation, an oppressive system of taxation was used to fill the coffers of the ruling bureaucrats and soldiers.

Do some of these themes sound vaguely familiar?

The pandemic lockdown response saw the M2 money supply (cash and bank deposits) increase drastically in New Zealand due to quantitative easing. Increasing some 35% from 2019 to 2022.

Yes, some similarities with the debasing of the silver denarius. The real value of a unit of exchange falls precariously.

Pay rises to keep ahead of inflation seem to be awarded first to those on government payroll. The private sector was not always able to keep pace.

Again, similarities with the Roman situation. The ruling bureaucrats maintained their spending power, often to the detriment of the rest of the economy.

Then as now, society has become more divided. More dangerous. With economic freedom eroded.

New ideological principles aligned to state control have begun to manifest in education, civil service, and in new laws.

There appears a clear link between inflation, control, division, and rising levels of social disorder.

Perhaps it is no surprise that one of the more popular shows to come on TVNZ recently is Negotiator.

Source: ScreenScribe

It is a police thriller in Portuguese (with subtitles). Set in São Paulo, Brazil. A city that has struggled with high rates of crime. And a country, that over the past 40 years, has struggled with hyperinflation.

From Auckland to Rome to São Paulo; the financially savvy do not stand back and watch their wealth erode…

There are a couple of things they might be doing:

- Diversifying their money by investing in other markets globally. Diversification is the one free lunch in finance.

- Investing in productive assets. Such as listed companies with high quality assets and growing revenue streams.

- Investing in assets that provide high income yield. Like listed real estate companies with manageable gearing.

- On that note, being wary of investing in assets encumbered with a lot of debt. Houses seem attractive during times of inflation. But if their purchase depends on hefty mortgages, the value of that asset class will get hammered by rising interest rates.

Monetary, political, economic, and social issues are very much intertwined.

The nature of many governments is that monetary policy is first used to serve the aims of the state.

Of course, not all governments are bad. Most intend to improve the prosperity of every citizen.

But the inadvertent reach for more control, alongside a focus on minority interests, can lead to unintended consequences.

Those consequences are a rising cost of living, more inequality, more financial stress, and a dangerous crime wave.

Indeed, these are strange days.

For those who would like to explore more reporting on what the financially savvy are doing to navigate this…

I encourage you to grow your knowledge and support our work at Wealth Morning by taking out a premium news subscription today.

For more details and an unusual special offer, please view here.

Regards,

Simon Angelo

Editor, Wealth Morning

(This article is the editorial content of this periodical. It is the author’s personal opinion and commentary. It is general in nature and should not be construed as any financial or investment advice.)

Subscribe Now

Subscribe Now Login

Login Managed Accounts

Managed Accounts Quantum Wealth

Quantum Wealth

Simon is the Chief Executive Officer and Publisher at Wealth Morning. He has been investing in the markets since he was 17. He recently spent a couple of years working in the hedge-fund industry in Europe. Before this, he owned an award-winning professional-services business and online-learning company in Auckland for 20 years. He has completed the Certificate in Discretionary Investment Management from the Personal Finance Society (UK), has written a bestselling book, and manages global share portfolios.