Here in New Zealand, we have a housing crisis.

There weren’t enough homes to go around. So prices, especially in Auckland, reached ridiculous levels. As much as 11x median income.

By definition, to buy a home, you need to already have one to sell, be a cashed-up migrant from offshore, or have access to a family bank.

Last quarter, the average Auckland home price fell $140,000. A decline of about $1,500 a day.

As we warned last year, this was bound to happen. This could be just the start of things as the property super-cycle turns.

Now we are thrust into a new crisis.

The mass building of ‘medium-density’ town houses across our cities.

Some are not houses by any normal stretch of the imagination. They look like military bunkers. Lined up alongside each other, with any view potentially blocked by the bunker next door.

A development in Takapuna, Auckland. Source: Author photo

Of course, Auckland could do with more density in the right places. The Unitary Plan allowed for much of that before it was superseded by the new National-Labour bipartisan accord on enabling housing supply.

The trouble with enabling housing supply in this way is that it could lead to unexpected outcomes.

And that’s the key to any strategy. Indeed, to any investment. Predicting what the real outcome of an incentive may be.

Sadly, this understanding seems lacking in New Zealand politics.

Before I returned to New Zealand, I spent most of my holidays driving across France. And sometimes down to Italy.

My observation is that the French do infrastructure and housing rather well despite a much larger population.

There are medium to high-rise apartment blocks around town centres. And larger homes in the suburbs or countryside.

Planning is tight. You can be fined up to €300,000 for works without consent, or spend two years in jail.

Rules are also localised to suit particular areas — not directed by government. And mayors themselves have further powers to impose fines of up to €500 a day for unauthorised construction work.

If that’s not enough, neighbours often alert concerning works to their local authorities, who may also bring civil actions for damages.

In spite of all this, good quality housing seems remarkably affordable across much of France. As is some of the world’s best food and wine.

Towns and cities are also pretty well connected. Uncluttered motorways let you zoom across the country at speeds of 130 km/h. A rail network links up urban areas. And electricity supply is more robust than other European neighbours, thanks to 67% generation by nuclear.

Suffice to say, when I see the desperate uglification of pockets of Auckland, I miss Europe. But I also wonder if the incentives for Kiwi investors are now totally wrong.

The French, I guess, have had a long time to learn about misplaced incentives…

Goodhart’s law

In the early 1900s, France controlled Hanoi, Vietnam.

The wealthier suburbs had a French sewer system. They also had a rat problem.

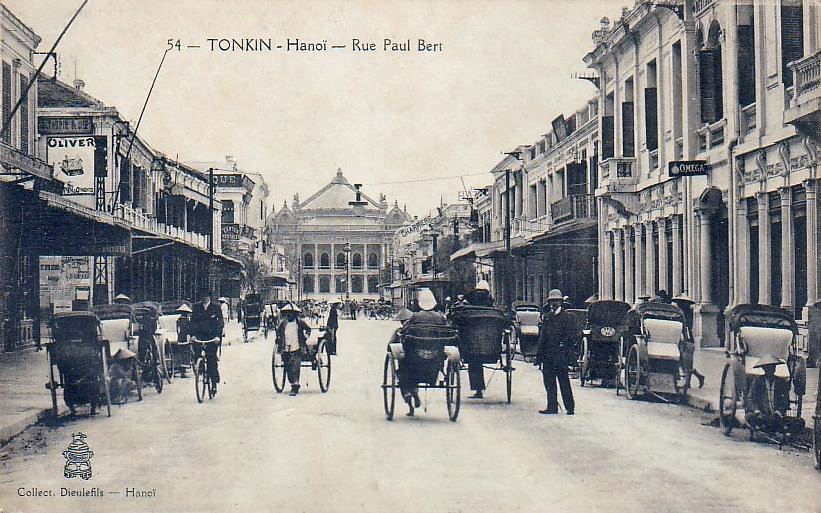

Turn of the century Hanoi — Rue Paul Bert (now Trang Tien Street). Source: Atlas Obscura

The authorities set up an incentive they thought would resolve the problem. Bring in the tail of a slaughtered rat and you’d be paid for it.

Once the scheme was up and running, they started to notice a peculiar happening. There were even more rats breeding in the tunnels. Some without tails!

Goodhart’s law states that ‘when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure’.

Charles Goodhart was an economist who — surprise, surprise — came up with this critique when analysing monetary policy.

Interestingly, he advised on and supported the Reserve Bank of New Zealand Act 1989.

This gave the Bank sole responsibility to vary interest rates to meet agreed inflation targets. And up until recently, it worked rather well.

However, in 2018, the Bank was given a new policy target of promoting maximum sustainable employment. And in 2021, a new remit to consider sustainable house prices.

During Covid, the bank swayed across targets to ease money supply. And the government stepped in to fund employment attrition due to the lockdowns it enforced.

If you pay for rat tails, that doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll decrease the rat population.

If you flood economies with cheap money following the short, sharp shock of Covid — you’ll end up with asset bubbles that set off a painful lag of correction.

And if you then ask your central bank to try and juggle employment, house prices, the Treaty of Waitangi, and inflation — well, I’d suggest you grab some popcorn. There could be many twists and turns.

Further, Labour and National seem to now believe they can solve Auckland’s housing crisis by forcing new rules most residents don’t seem to want.

Let’s face it. Developers — to put it kindly — vary in quality.

If you allow them to build rows of housing that fail to match the demands of a lifestyle city, you’ll end up with new problems.

Developers want to maximise their margins. Sell out the project. Move on the next one.

But projects are starting to stall or fall over.

Last year, Auckland saw a net loss of 13,500 residents.

Surely, some of the worst designs in this intensification will only contribute to the mental health problems that are evident across our communities?

People may be stuck in sunless units looking into one another. Neighbours become anguished as bunker rows steal their light and street parking.

But this is a fight for the people of Auckland and perhaps their new mayor.

Central government should not be interfering with local planning on the ground.

Sustainable house pricing is a fraught measure and target for a central bank trying to contain inflation. On top of employment considerations.

The incentive mix could risk a further painful drawdown to house prices. Or inflation running out of control. And a serious degradation of living standards.

Do the right thing at the extremes

If you’ve been investing through historic market cycles, you’ll have experienced the long pain of the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. And the short, sharp shock of the 2020 Covid-19 crisis.

What have I learnt from these?

Don’t worry about the market going up or down. Many investors are irrational. They’ll sell on fear and buy on greed. Short-term incentives encourage rats and wrong decisions.

Providing you have a reasonable time horizon, I keep to one simple rule: find value. Low prices are your friend.

It’s a simple long incentive with clarity of focus and vision.

Through this inflationary crisis, I’ve been deploying my own money in the global markets when and where I see value. And the same goes for the funds of our Wholesale Clients.

Perhaps you’d like to learn more about this process?

For qualified investors, we provide managed brokerage accounts under their own control. With a proven strategy that has beaten its benchmark for many years.

If you’d like to discuss this market and the opportunities it presents, please get in touch by requesting a free consultation today.

Regards,

Simon Angelo

Editor, Wealth Morning

(This article is general in nature and should not be construed as any financial or investment advice).

Simon is the Chief Executive Officer and Publisher at Wealth Morning. He has been investing in the markets since he was 17. He recently spent a couple of years working in the hedge-fund industry in Europe. Before this, he owned an award-winning professional-services business and online-learning company in Auckland for 20 years. He has completed the Certificate in Discretionary Investment Management from the Personal Finance Society (UK), has written a bestselling book, and manages global share portfolios.