Radio and social media are littered with an alluring promise.

If you buy a rental property with the help of a good realtor, you can secure your financial future.

You know how it goes. It will be brick and tile. In an area of endless demand. And you’ll help solve the housing crisis in this country.

The message has some self-evident logic. If you own a home, it’s shot up in value. So if you owned two or three, imagine the position you’d be in!

Like most such promises, only a small number of people will really profit. And the opportunity may have already passed. I suspect by the time the ride is advertised, the horse has bolted some time ago.

I’ve been a landlord recently. And a tenant a long while back.

As a landlord, it goes like this…

If you have a decent chunk of equity in your rental, you end up scratching your head on the return you’re actually receiving. It may not be enough when compared with other investments like dividend-paying shares.

You may see a gross yield of 4%. If you’re lucky. But that is gross. Before you deduct rates, insurance, and a myriad of repair and compliance costs.

Then there is your time. The stress. There will be times in the life of every rental when you need to get involved. Even with a property manager.

My experience as a landlord was that the return from rent alone would have made the whole exercise pointless. There had to be the golden goose of rapid capital growth waiting in the wings.

As the property super-cycle starts to turn, is there still this capital growth upside?

In a small country like New Zealand, that depends on immigration policy. The one reliable source on the demand side.

But if there’s one thing governments have learnt over the past two decades, it is this: the real return from immigration takes a long time to come through.

Migrants take a housing space, a road space, often some school spaces, and occasionally a hospital bed. Do they bring any of those investments with them when they arrive on the aeroplane?

When you’re short of doctors, nurses, builders, and maths teachers, that is a different matter. But it’s the lifestyle immigration with questionable investment benefit that we’re starting to take a long hard look at.

Read: it’s unwise to guarantee growth in housing investment via unsustainable immigration.

So, in a nutshell, my experience as a landlord would have been a fool’s errand but for the capital growth. A lot of hard work, growing compliance, and scant return. Guaranteed capital growth is required.

Of course, there are other reasons people buy second homes. An alternate location. The hidden benefit of forced savings, as most mortgages need gradual repayment of a capital sum.

As a tenant, it’s even worse…

The last time I rented, I was in a shared situation.

I was single. The $100 a week I paid for a room in a Remuera villa was a tiny fraction of my income.

Mind you, this was the 1990s. A different era.

But imagine the situation for a growing number of families. Today.

According to Barfoot & Thompson, the median rent for a 3-bedroom home in Auckland topped $600 last year. That’s over $31,000 a year.

The average salary in Auckland according to Payscale is $69,000 a year. After tax, you’re left with around $55,000.

Clearly, renting a home in Auckland needs two average salaries. And above-average salaries to afford the saving of a deposit for your own home.

Whether landlord or a tenant, the New Zealand housing market is not a great situation.

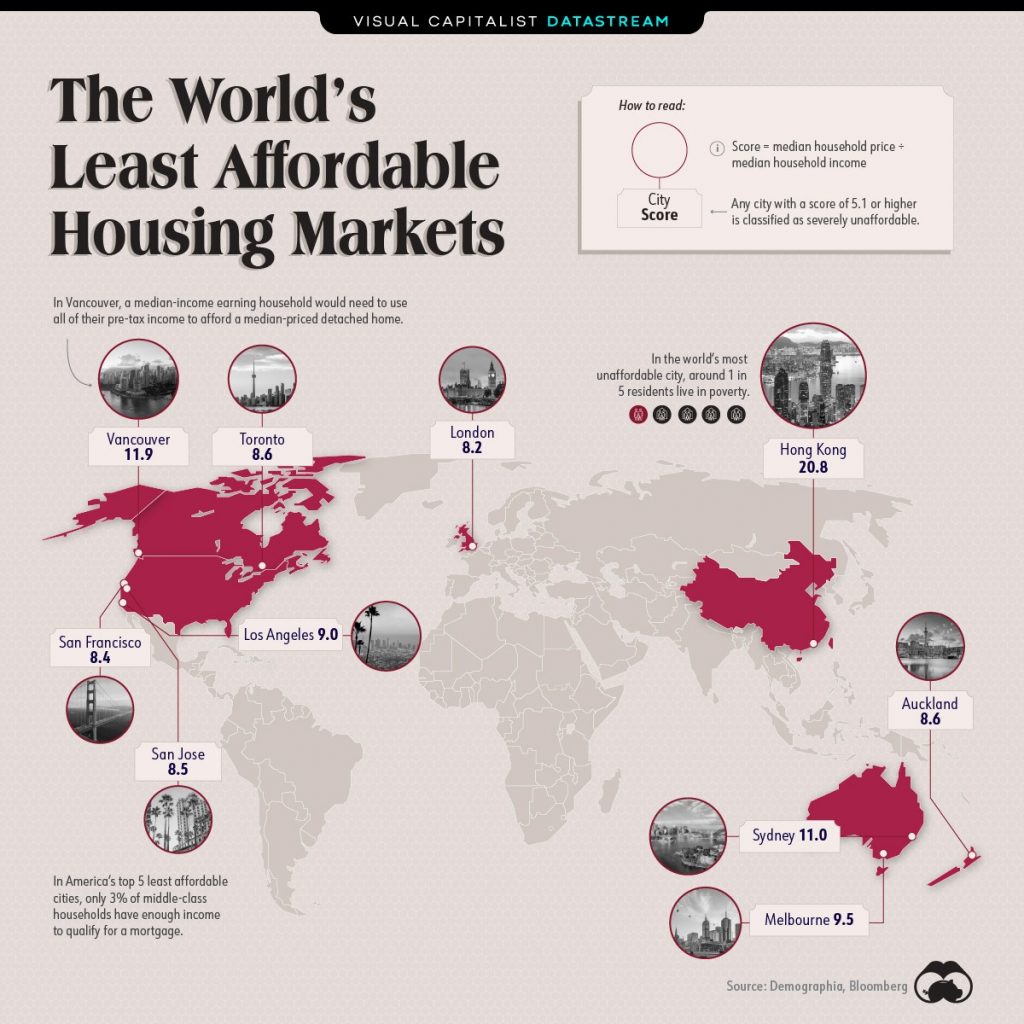

The most unaffordable housing markets all feature contained urban areas and more incomers than existing housing supply can cope with. Source: Visual Capitalist, February 2021

So, what can be done?

We got into this dire situation because housing and construction could not cope with population growth. Maybe it’s starting to catch up. At least in Auckland. But judging by price-to-income multiples, not much. Yet.

Well, there was the ‘Enabling Housing Supply’ amendment bill that comes into force this August. Allowing dense development in major cities with few restrictions.

Follow any of your neighbourhood chats on social media about this?

The Enabling Housing Supply move seems universally hated. Then National and Labour are blamed for their woeful record on causing the problem to begin with.

A typical comment on my local group goes like this: ‘National are the architects of the housing crisis. Of course they support this legislation. Where else will the people they brought into the country live?’

ACT was the only party in government who opposed the bill, arguing it would lead to chaos. Since people had bought into suburbs not expecting rules to suddenly change. They also argued it wouldn’t work since it doesn’t fund councils to provide the necessary infrastructure.

I agree. This bill is a white elephant. It relies on existing homes being sold — which takes years. And the character of established neighbourhoods being gradually detonated.

So, what do the parties in Parliament propose?

Labour has gone as far as they can

To their credit, house prices are slowing and an avalanche of homes is coming to the market. But this may be the slow melt of a very high peak.

Meanwhile, renters are paying some of the highest rents on record. And most landlords you speak to feel put upon by the squeeze of compliance and the removal of tax deductions.

National promises to get stuck into zoning and removing the Auckland boundary

They also want to establish a ‘Housing Infrastructure Fund’ and put in place new finance . Otherwise, there’s scant policy proposal I can discern at this point.

The Greens want a capital-gains tax and land sales restricted to residents

They want a warrant of fitness for rentals. And a range of market and non-market interventions to enable more affordable supply.

ACT wants to completely repeal the RMA and focus on infrastructure

They want to liberalise zoning and planning regulations, while retaining local autonomy. And they want to share GST with councils to encourage infrastructure development. They also want a building insurance scheme while aligning the approval of building materials with like jurisdictions.

In a nutshell…

ACT sees building and development in New Zealand hamstrung by restrictive policy. The Greens believe more intervention is required to level the playing field. National is focused on infrastructure but has yet to propose specific policy. And Labour has already thrown the bath at the market.

Understanding the housing market

Housing is a market like any other. Subject to supply and demand. Governments can tinker and hope their changes work.

The simple reality is New Zealand has not managed to increase housing supply anywhere near fast enough for the demand surge it has been under. And this has been the case for nearly two decades.

Take a look at more sustainable housing markets — the majority of which appear to exist in the US.

If we combine findings, certain facts rise:

- 2022 Demographia International Housing Affordability says: ‘Whatever its advantages, urban containment has been associated with huge cost of living and housing cost escalation relative to incomes, thereby increasing poverty and inequality.’

- Research by Motu, a think tank researching public-good focused economics, found ‘that a one percent increase in population from migration at the national level is associated with a 12.6 percent increase in house prices.’

- From 2015 to 2020, New Zealand’s population growth averaged 2% per year. More than half of this growth came from net migration as opposed to natural increase. Motu appears correct. We should have expected at least a 13% annual increase year-on-year.

- Immigration is beneficial since it brings skills, diversity, and investment. Yet, if you do not want house prices increasing unsustainably, you need to ensure construction and zoning can cope with the increase. Or you need to focus immigration on needed skills and investment back into housing.

- Clearly, urban containment is exacerbating prices in Auckland and other cities. Forcing mass density at the cost of amenity (as has been done by the Enabling Supply bill) has unintended consequences. It may destroy neighbourhoods slowly, savage local democracy, and trigger anger without actually resolving the problem anytime soon.

Digesting the findings

- Urban containment needs to be mitigated with more ability for cities to expand out.

- We can’t yet build for the level of immigrants we’ve had in the past.

- Development is hamstrung by lack of infrastructure and an overregulated building sector.

- Democracy needs to be returned to Councils to respond to their local needs.

- Councils need a better share of the revenue from development — not saddled with costs without benefit.

- We have to be prepared to see house prices fall 20% — or even 40% as they did in the 1970s — to correct the levels of imbalance currently seen.

- If we want a fair housing market, where all can take part, there will need to be a painful period of reckoning.

- Experience in Europe and Singapore shows more social housing can help create affordability across the whole market by moderating demand. In Vienna, Austria, social housing accounts for 23% of housing stock. In densely packed Singapore, 80%.

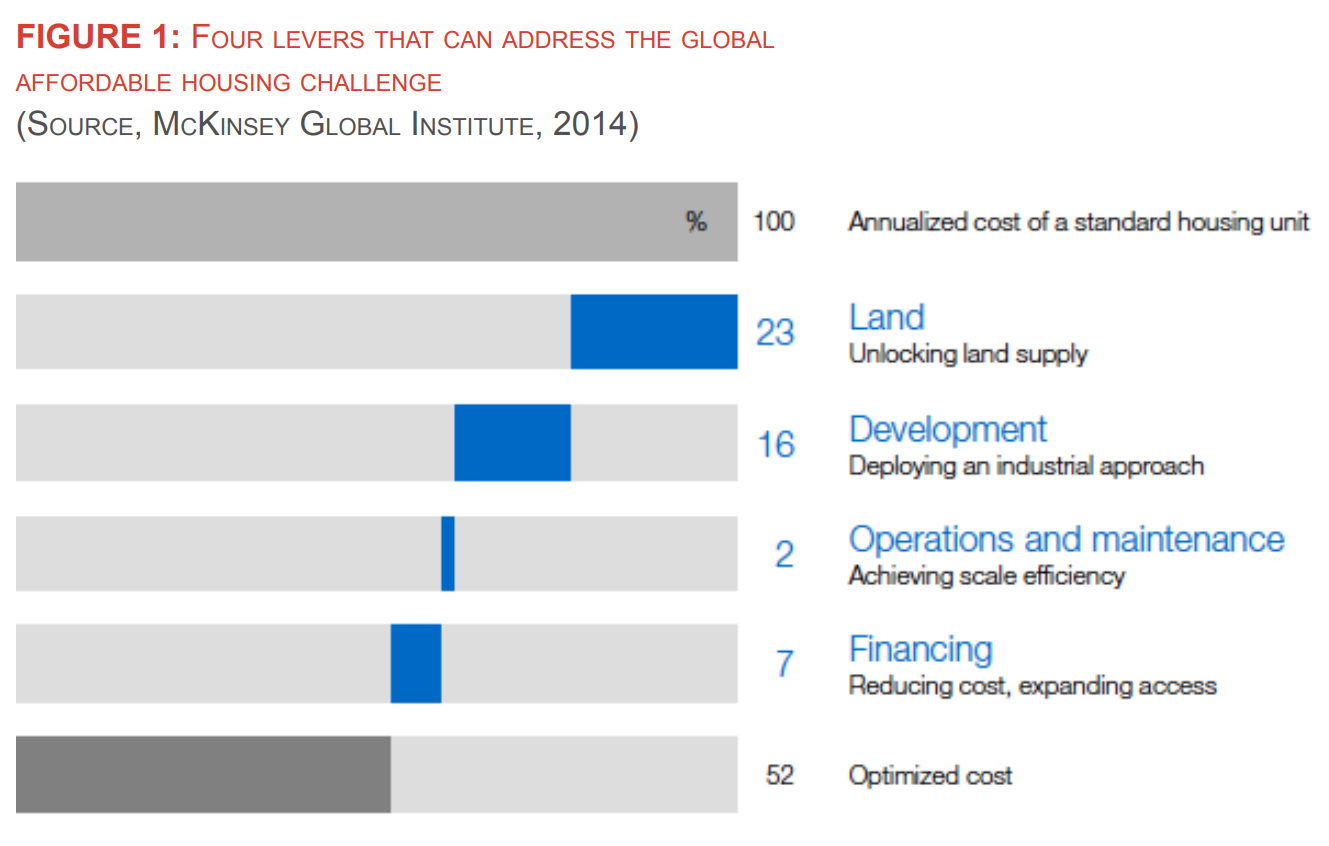

Further, if we look at four key levers, unlocking land supply while developing and financing at scale are key:

Source: International Examples of Affordable Housing, The URBED Trust

For investors, financial markets may allow for a much more diverse range of investment opportunity. Across sectors and locations well beyond this explosive housing market.

In this area, New Zealand needs to see more listed entities working in the housing sector. For example, listed homebuilders and developers as we see on the Australian, UK, and US stock markets.

Recent market entrant Winton Land [NZX:WIN] is one such example. We need more.

This will take time. And for these businesses to flourish, urban containment, and building cost and restrictions need to reduce.

One thing is plain. We need to see housing not as a speculative asset that should keep rising in value, but as an affordable place to live for a range of income levels. And a driver of secure and happy communities.

Regards,

Simon Angelo

Editor, Wealth Morning

Important disclosures

Simon Angelo owns shares in listed homebuilders in the UK, US, and Australia via portfolio manager Vistafolio.

(This article is general in nature and should not be construed as any financial or investment advice. To obtain guidance for your specific situation, please seek independent financial advice.)

Simon is the Chief Executive Officer and Publisher at Wealth Morning. He has been investing in the markets since he was 17. He recently spent a couple of years working in the hedge-fund industry in Europe. Before this, he owned an award-winning professional-services business and online-learning company in Auckland for 20 years. He has completed the Certificate in Discretionary Investment Management from the Personal Finance Society (UK), has written a bestselling book, and manages global share portfolios.