‘The prudent sees danger and hides himself, but the simple go on and suffer for it.’

—Proverbs 22:3

Cash was a lot more prevalent when I was growing up.

There was a boy, couple of years older than me, who had a knack for finding it. Usually loose coins in the gutter outside a dairy. Once, a $20 note blowing down the pavement.

But he was always flush with the folding and jingling stuff thanks to a gimlet eye.

He has done well in business as an adult, I hear.

In our small rural town, it was a surprise how careless people were when it came to dropping their money. But, of course, these were the days before plastic cards. When friend’s parents had cash boxes at home, raiding that to send their children down to the video shop.

These were also the days when inflation ran at double digits. When money was not particularly worthwhile unless you immediately put it into something. Even a ‘layby’ on an object of desire when you didn’t yet have the cash.

Inflationary pressures eventually led to bubbles. The stock market crashed in 1987.

Things came to a head with the Reserve Bank Act 1989.

From that point on, the Reserve Bank was charged with keeping the CPI increasing no more than 0% to 2%, and later, 0% to 3%.

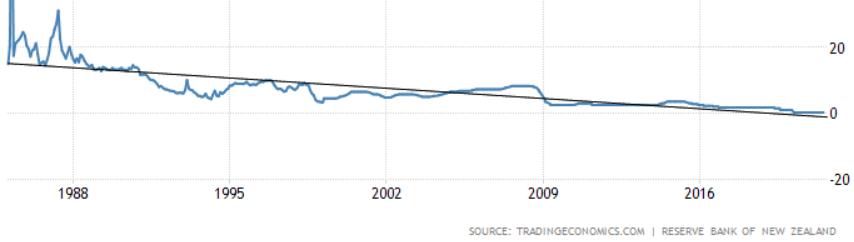

A 30-year trend in interest rates

Since 1989, we have seen New Zealand interest rates coming down from the high teens toward zero.

In fact, the OCR has dropped as low as 0.25%.

You might say the Reserve Bank Act has worked. Stable prices. Ever lower interest rates. At least until now.

But this trend line misses certain areas of danger

We may have been lulled into a false sense of security.

Much of what the CPI measures comes down to everyday goods and services.

When China joined the WTO in 2001, the process of bringing the productive capacity of up to 1.4 billion people to global supply chains really began.

Costs came down. Meanwhile, technology and automation further reduced costs. And as the New Zealand population started to age, people reduced their expenditure anyway.

As a result of this ageing, successive governments commenced more aggressive immigration policies from the 1990s. This led to an influx in one key area, not easily measured by the CPI.

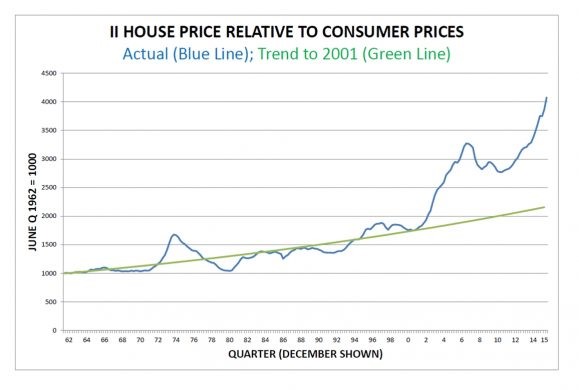

Runaway house prices

Since about 2000, when the population started to grow more rapidly, Kiwi homes have inflated far beyond the CPI:

Source: Briefing Papers, Brian Easton

The steepening line from 2012 has continued a mad and rapid ascent.

Population growth via migration is only part of the reason. The real reason is an influx of money into this particular market.

Immigration brings in foreign exchange. An influx of fresh cash.

But very low interest rates and ease of borrowing from large banks focused on mortgage revenue brings in even more influx.

And Covid-19 has seen a new approach in monetary policy here. A tool that really got to work during the GFC. Not only tightening or loosening of the money supply via interest rates, but increasing the money supply via ‘large-scale asset purchases’ — bond buying or ‘money printing’.

Of course, governments love cheap money. Once they have it, they can issue popular economic recovery fixes such as wage subsidies. And propose very expensive cycle and walking bridges across Auckland Harbour. They can ‘print jobs’, and voters love it. At least in the short-run.

Those same voters are not stupid.

They sense what an influx of money means: here in New Zealand, too much money chasing too few homes. And they fear they will miss out. Not only themselves but their children. And their children’s children.

The trouble comes when wages fail to keep up with increasing prices. It is already a very hard ask to rely on wages alone to fund the average house in Auckland.

When the lag between wages and prices becomes too great, and there is little other influx of money, the bottom can fall out of a market.

The Spanish price revolution

17th century Europe presents one of the first major studies of inflation.

Gold and silver from Spanish conquests in South America fuelled expansion of the Spanish money supply. Source: National Geographic

The Spanish treasure fleet exploiting the New World returned to Europe with a large influx of gold and silver.

This led to a dramatic increase in ‘specie’ — or commodity money. It enlarged the money supply. As we see today with stimulus, money printing, hitherto population growth, and ultra-low interest rates.

History shows us the damaging impacts on the Spanish economy. A balance of payments deficit grew. Spanish public debt reached harmful levels. It was from this point that the economy and empire began to unwind.

Is there one lesson we can take from this?

The decline of Spain mirrors the decline of Rome.

Both empires procured a massive influx of wealth and money outside of productivity in their own economies. Spain, from the American colonies. Rome, from its conquests.

And both governments threw that money at every problem that arose, inflating and even debasing the real value of their currencies. And, crucially, providing no incentive to evolve their own internal economies.

In the end, inflating and borrowing only kicks the can down the road. Someday, the road ends.

The only real solution is to produce value. And perhaps invest in the best businesses that do so to protect your wealth.

The banker’s first swing of the scythe

Regards,

Simon Angelo

Editor, Wealth Morning

(This article is general in nature and should not be construed as any financial or investment advice. To obtain guidance for your specific situation, please seek independent financial advice.)

Simon is the Chief Executive Officer and Publisher at Wealth Morning. He has been investing in the markets since he was 17. He recently spent a couple of years working in the hedge-fund industry in Europe. Before this, he owned an award-winning professional-services business and online-learning company in Auckland for 20 years. He has completed the Certificate in Discretionary Investment Management from the Personal Finance Society (UK), has written a bestselling book, and manages global share portfolios.