My colleague has been trying to persuade his parents to invest in the markets.

They ran a good business for many years. Retired. Then put the nest egg into term deposits.

With rates now in the low three-percents, they’re finally considering shares. Probably through managed funds.

Personally, I’d prefer to own the shares direct. That avoids blind pooling. Redemption notice periods. And so forth. But that’s another discussion.

For those wanting to invest in shares direct, usually on the NZX, I then get the question: ‘Which shares are you buying?’

The answer is these days I struggle to find much value on the NZX.

Prices have risen so much; valuation multiples now seem ahead of Australia and certainly Europe.

It’s a small exchange. The larger high-yield businesses attract investment from all around the world. Many stocks there now seem in ‘Romeo and Juliet’ territory.

The Romeo and Juliet effect refers to a heightened desire for something due to it not being readily available. People pay silly prices for this reason.

So why are investors wanting to get in now — when they could have got in years ago when prices were down and volatile?

Loss aversion and zero-risk bias

The emotions around loss are thought to be twice as powerful as those around gain.

I once lost my parking ticket in France and had to pay 20 euros or so to get out of the car park. I was berating myself for over an hour until I realised that my share portfolio probably moved up or down by more than that amount every few moments.

When we see shares falling, loss aversion and fear kicks in. And people are wired to eliminate risk.

Therefore, my colleagues’ parents prefer to put their nest egg into term deposits at 3%. After inflation and tax, the real return is close to zero. Yet, excepting bank failure, most risk is eliminated.

I met a similar gentleman who had a significant amount on deposit with Westpac [ASX:WBC].

By becoming a shareholder, he could have earned a dividend twice that paid on his deposit. And, at current price, possibly be poised for some capital growth upside.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Equity ownership is going to have risks. The share price can rise as well as fall. Dividends can be reduced or, in lean times, get cut altogether.

Yet, as I’ll show you in a moment, those able to avoid zero-risk bias tend to capture the largesse of gains over the long run.

When we fall victim to zero-risk bias, we often end up in situations that are much worse than the somewhat riskier path we might have taken.

In the ’50s, the US Food Act sought to prohibit food that contained any cancer-causing substance. It was focused on achieving zero risk of cancer. Seems like a good ban, doesn’t it? In fact, this ended up leading to the use of more dangerous food additives which have caused far more illness and death than the minor-risk small proportions of carcinogens may have presented.

This goes the same way with wealth.

My colleague with the risk-shy parents also sent me a fascinating study. It shows that the top 1% of households in the US have increased their net worth by 650% since 1989. The bottom 50% grew their wealth by only 170% during the same period.

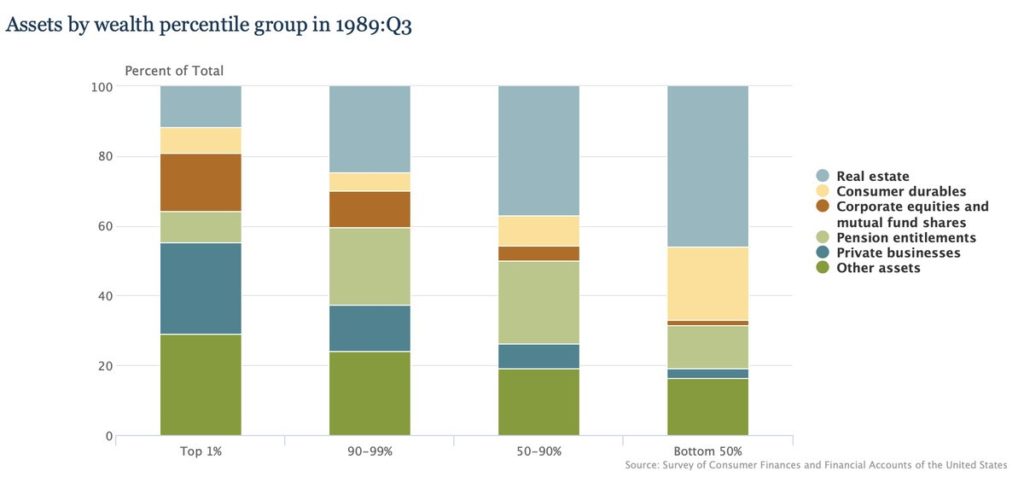

Federal Reserve figures indicate in 1989 the levels of risk those households took on:

As we can see, the top 1% had most of their wealth in businesses and shares. The bottom 50% mostly real estate — and tellingly, almost no shares.

Of course, the past 30 years have been a great time to own businesses. The S&P 500 is up tenfold before dividends.

The value of risk gets ignored

I came across a guy the other day — retired at a young age.

His profile said: ‘Early-stage Xero investor’.

Then I realised why he was wealthy.

Xero [ASX:XRO] IPO’d on the NZX in 2007, raising $15 million with shares at $1 each.

If you’d held those shares until now, you’d have made over 9,000% return. (Shares today trade at around AUD$100).

What people fail to realise, however, is the risk early-stage Xero investors took on.

When the company IPO’d, it failed to meet its raise target. There were little assets. Prospects were uncertain. It was a risky and speculative venture. I didn’t invest. Warren Buffet likely wouldn’t have invested. Nor would any conventional value investor.

Those who took that level of risk deserve the tens of thousands — or even millions — they’ve earned.

The trouble is, risk is invisible. As are years of work and patience. We only see the resulting fortune and assume some people are just lucky.

So, in your investing, beware of zero-risk bias. Want reward and return? You’re going to have to take some risk.

Because life is filled with risks and uncertainty. It’s about managing it and harnessing its rewards. Eliminate it altogether and you could end up with something much worse — nothing.

Regards,

Simon Angelo

Editor, Wealth Morning

Important disclosures

Simon Angelo owns shares in Westpac Banking Corp [ASX:WBC] via wealth manager Vistafolio.

(This article is general in nature and should not be construed as any financial or investment advice. To obtain guidance for your specific situation, please seek independent financial advice.)

Simon is the Chief Executive Officer and Publisher at Wealth Morning. He has been investing in the markets since he was 17. He recently spent a couple of years working in the hedge-fund industry in Europe. Before this, he owned an award-winning professional-services business and online-learning company in Auckland for 20 years. He has completed the Certificate in Discretionary Investment Management from the Personal Finance Society (UK), has written a bestselling book, and manages global share portfolios.