My favourite Italian restaurant has been closed since the lockdowns.

Initially, I thought it was a victim of those forced closures. But it turns out the actual reason was the rain, the flooding of the restaurant, and Auckland’s shortage of tradespeople.

Many situations are not what you think on first glance.

The arrival of New Zealand’s OECD report last month is a similar case. This time, it has flagged rapidly rising government debt against an ageing population. And terrible rates of productivity.

Those are factors you may care to think about while dining at an Italian restaurant. Because they are most commonly associated with long-running economic malaise seen in a much larger trading economy: Italy. Recently brought to a head by the pandemic.

Source: Future of Europe / Mauro Scrobogna

The Italian economy fascinates me.

On one hand, it is Europe’s third-largest, a significant exporter and producer of many beautiful products. The ultimate tourist destination.

Yet it is perennially facing debt, stagnant growth, and woefully high youth unemployment.

Moreover, it provides lessons on good debt and bad debt. Lessons the New Zealand OECD report has highlighted right now.

As a Wealth Morning reader, you probably already have an understanding of good debt v. bad debt. Rich Dad Poor Dad 101.

Leverage is OK to buy assets that go up in value.

Otherwise, it’s not so OK.

But there are modern issues that Rich Dad didn’t foresee in his groundbreaking 2000 book.

Here are three problems we’re now facing:

- Governments took ‘bad debt’ to dig us out of Covid, and now that has wider ramifications for our economy

- Debt is getting repriced due to inflation

- Certain assets we leveraged on could be in a bubble

Let’s start with the issue of government debt here in New Zealand.

The OECD’s January 2022 Economy Survey has sounded the alarm:

‘The fiscal measures taken to support the economy during the COVID-19 crisis have substantially increased the government debt-to-GDP ratio. On unchanged policies, the debt-to-GDP ratio will rise considerably over coming decades owing to population ageing. Additional measures are needed to put public finances on a sustainable medium-term path, including linking the pension eligibility age to life expectancy.’

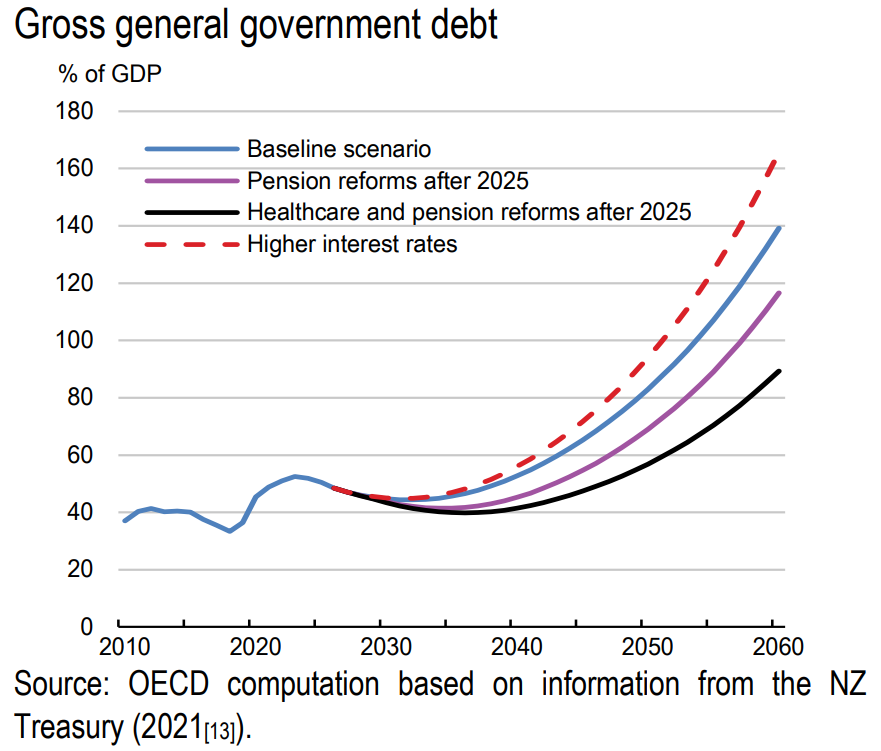

Left unchecked, we’re facing a debt-to-GDP ratio as high as 100% by 2050. And it could reach 160% by 2060:

Keep in mind, responsible debt-to-GDP ceilings for a small, open trading economy like New Zealand’s would be below 60%.

The EU’s Stability and Growth Pact for its members targets a debt limit of 60%. Though this was suspended during the pandemic.

We are already sailing close to these limits. Nor are we members of trade and stability unions like the EU to cushion us from shocks or disasters.

Meanwhile, New Zealand’s growth is constrained by infrastructure gaps. From a heaving harbour bridge in Auckland to housing shortages and transport strains across the country.

While borrowing for infrastructure investment may be seen as ‘good debt’, much borrowing since 2020 has been to pay wages lost during aggressive Covid-19 lockdowns. Debt consumed by living, with no assets to show at the end, is financially speaking ‘bad debt’.

Though there is the argument that wage subsidies have prevented many businesses from going under.

Lessons from Italy

Italy’s public debt, following the pandemic, is closing on 160% of GDP.

But the worst effects of this have been staved off by the following:

- The ECB’s purchase since March 2020 of 250 billion euros of Italian debt under its Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP)

- This has kept a lid on borrowing costs, with Italy’s 10-year bond yield still low

- Italy still has some 200 billion euros in grants and cheap loans from the EU’s Recovery Fund, available through 2026 — provided the country continues to meet the policy conditions imposed by Brussels

Of course, it is likely Italian interest rates will spike once the bond-buying programme ends. This will have ramifications across the economy.

Further, low interest rates and grants are no panacea to structural economic problems:

- Italy has a high unemployment rate, particularly amongst youth, who are often overqualified in the wrong fields

- Productivity is stagnant

- There is a lack of investment in technology and education

- Bureaucracy is stifling

- The population is ageing rapidly

While New Zealand has a very low unemployment rate, this country too is grappling with poor productivity, a lack of investment, an ageing population, and more recently, stifling bureaucracy.

Should our government be unable to rein in debt, there is a very real danger of New Zealand once again starting to look like the Italy of the South Pacific. Without any EU support.

However, we are a very long way from the 160% debt-to-GDP Italy nears.

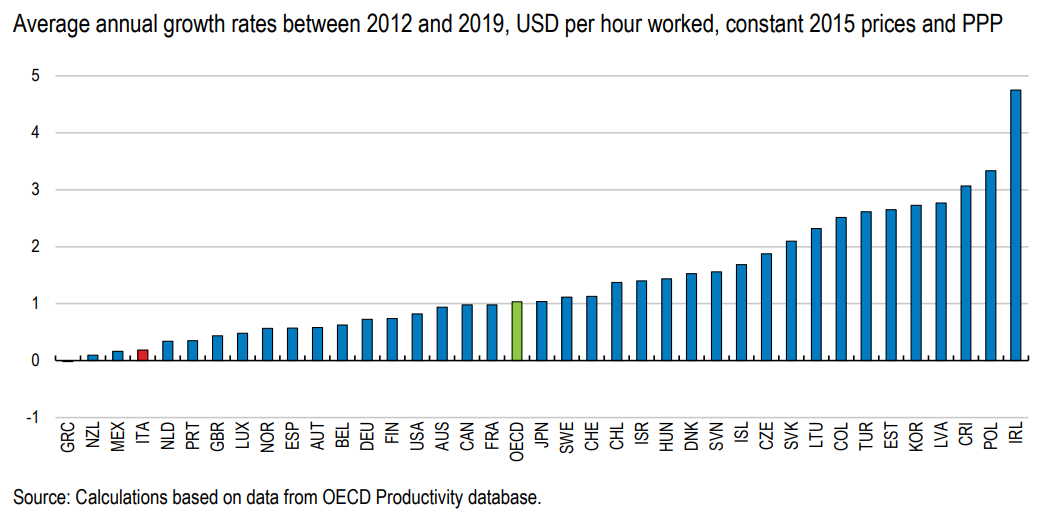

The real issue is productivity, with too much money in housing.

If you doubt how bad New Zealand productivity is, consider this: the OECD flagged productivity as one of Italy’s most pernicious economic threats in the same report prepared for that country.

New Zealand’s productivity growth sits even worse:

Source: OECD Economic Survey, Italy, September 2021

Repricing of debt

For the average Kiwi, the economy hasn’t been productive enough. This means debt has had to increase to fund our lifestyle. And now cheap debt needs to be repriced.

This impacts mortgages. And the ability to borrow or invest.

The risk premium on any investment increases. If bank deposit rates rise to 5%, why take risk to achieve 5%?

Meanwhile, the inflation we are seeing creates a hurdle.

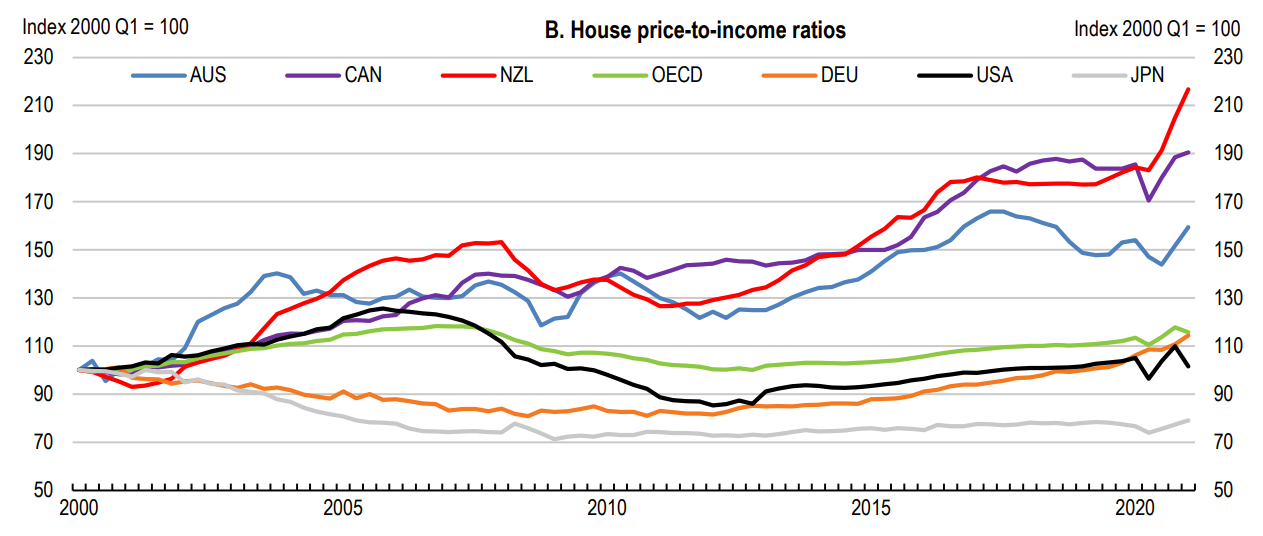

Now, some commentators are suggesting all this could lead to steep drawdown in house prices.

Warnings of 20% or more have been seen in Canada. This is a similarly bubbled real estate market, where half of all Canadians could not afford to buy a home today.

Like Canada, New Zealand has had very high rates of net migration. The lifestyle and space of both countries are attractive to immigrants. Who still see value compared to much more densely populated nations.

Immigration will probably help both countries preserve their housing markets with foreign cash and avoid a crash.

But in the case of New Zealand, this will not improve productivity in the short-run. Nor will it reduce the need to build infrastructure or slow down debt accumulation.

The only real solution to a sustainable housing market and sustainable levels of government and household debt is to increase productivity.

Continuing to kick the can down the road with high local debt and investment via immigration to fill the cash void will be to continue to create a country for foreigners. Not locals.

And this is already being seen in the woeful cost of housing in New Zealand, compared to even Canada:

Source: OECD Economic Survey, New Zealand, January 2022

Italy, of course, does not have this problem.

Compared to New Zealand or Canada, housing is more affordable, and Italian households are among the least indebted in Europe.

But the structural employment problems and ageing rate in Italy present greater challenges.

New Zealand has an opportunity to develop a population policy in relation to immigration that is sustainable. And to build a productivity focus with lighter touch regulation.

Housing bubble

Property markets run on much longer cycles than sharemarkets.

My preference for investment is in sharemarkets. Because they are more liquid, tend to recover from drawdown faster, and there are globally diversified choices across many different companies and industries.

Yield from dividend-paying stocks is also passive compared to property rent, which often requires extensive management.

Of course, you cannot live in a line of stock or provide accommodation for your family. Or take out a sizeable mortgage on it — though some leverage is possible.

Past experience with stock markets show that moderate inflation and the first rounds of interest rate rises tend to be benign.

It is when interest rate rises become sustained and aggressive that markets are pulled down.

It takes not one knife stab, but several to incapacitate the patient.

And this would likely be even more so in the case of heady property markets.

So, will the Kiwi housing bubble correct?

Resuming high net migration would likely hold that. Since it would continue to exacerbate the current shortage of housing in a tiny market.

Without that, building supply will catch up. Interest rates will make many mortgages untenable — particularly for investors.

It won’t happen initially, but it will happen following several rate hikes. And the current housing super-cycle could be over. With a drawdown far deeper and longer than may be seen in any sharemarket.

In a scenario with government debt above 100%, much higher interest rates, and an ageing population without replenishment, it’s hard not to see a very major correction. A deep correction.

There will be a painful swing of the economic sledgehammer to force this country to wake up to its imbalances. As all countries — from Italy to New Zealand — eventually must. Should they wish to retain their standard of living.

Regards,

Simon Angelo

Editor, Wealth Morning

Disclosures

The author invests directly in listed companies on the New Zealand and Italian Stock Exchanges via Portfolio Manager Vistafolio.

(This article is commentary and the author’s personal opinion only. It is general in nature and should not be construed as any financial or investment advice. To obtain guidance for your specific situation, please consult a licensed Financial Advice Provider.)

Simon is the Chief Executive Officer and Publisher at Wealth Morning. He has been investing in the markets since he was 17. He recently spent a couple of years working in the hedge-fund industry in Europe. Before this, he owned an award-winning professional-services business and online-learning company in Auckland for 20 years. He has completed the Certificate in Discretionary Investment Management from the Personal Finance Society (UK), has written a bestselling book, and manages global share portfolios.