There’s no denying it: Warren Buffett is a legend.

His company, Berkshire Hathaway [NYSE:BRK.A], has clocked in an average return of 20.5% per year since 1965.

Just think about this for a moment. 20.5% annually. For 55 years. That’s over half-a-century. Over two generations.

Buffett’s patience and prudence are well-known, backed by a track record that is formidable. They don’t call him the Oracle of Omaha for nothing.

And yet, more and more, you’re starting to see young investors emerge to challenge that orthodoxy. They’re bold and brash. And they aren’t afraid to thumb their noses at Buffett.

You tend to encounter such controversial views on social media and discussion forums:

- They say that Buffet is past his prime.

- They say his approach is silly and misguided.

- They believe it is no longer worthwhile to invest in what they call ‘boomer stocks’.

Why? Well, the proof, apparently, is in the pudding. They point to these facts:

- Over the past decade, Buffett’s stock picks have underperformed compared to the S&P 500 Index.

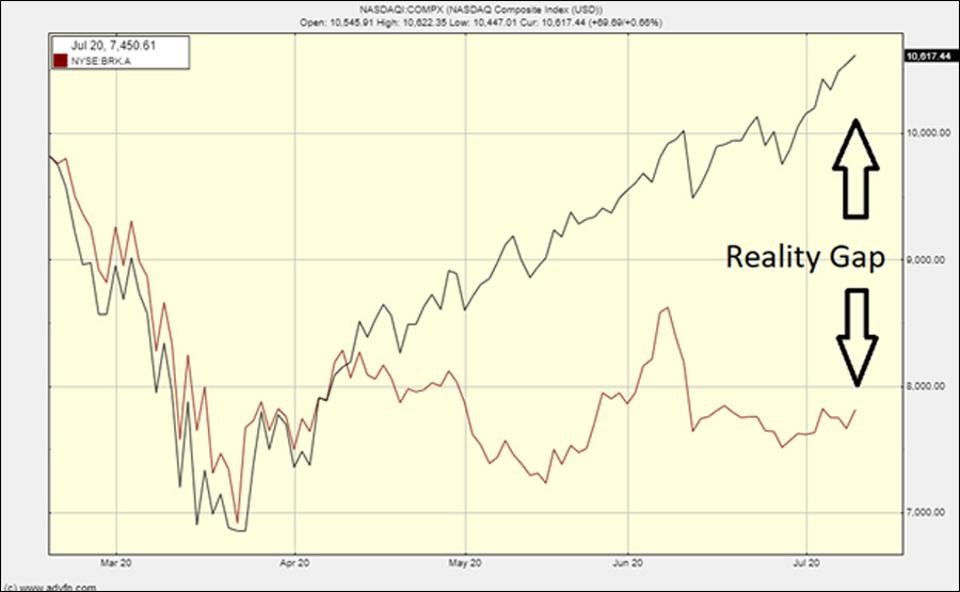

- When you look at the Nasdaq in 2020, that profit gap widens even more.

The Nasdaq and Buffett. Is there a reality gap? Source: Forbes

In the words of Neo from The Matrix, ‘Whoa!’

It’s clear that an ideological battle line have been drawn. And what we’re seeing now is a rivalry develop between two different personality types:

- The old-school value investors who believe in margin of safety and go for measured performance over the long-term.

- The new-school growth investors who disregard margin of safety and go for higher yield and quicker gratification.

Well, who is right? Who is wrong? And why does it matter so much?

Growth versus value

If you’re looking for a good example to understand this psychological conflict, you really don’t have the look far. Kiwi company Xero [ASX:XRO] is the perfect poster child.

Consider this:

- In the past five years, Xero’s stock price has jumped from around AUD $17 to $137

- That’s a growth surge of over 700%.

- Investing a theoretical sum of $100,000 in 2016 would see that money multiply to over $800,000 today.

- The company’s P/E ratio now sits at around 1,059.

So far as I know, Warren Buffett has never done an analysis on Xero. It probably exists outside his radar. Still, it’s easy enough for me to imagine what the Oracle of Omaha would say: ‘Gosh, steer clear of this fancy tech stock! It is shockingly overvalued!’

Overvalued? Well, what does that mean, exactly?

Source: Google

Here’s a simple shortcut to understanding value — the P/E ratio. Price to Earnings. It helps to think of this in terms of multiples:

- A P/E ratio of 1 equates to 1 year of a company’s earnings.

- A P/E ratio of 10 equates to 10 years of a company’s earnings.

- A P/E ratio of 1,059 equates to 1,059 years of a company’s earnings.

So, yeah, Xero could be overvalued. Buy this stock right now, and what you’re paying for is future optimism.

In fact, you’re actually paying for 1,059 years of future optimism.

That price point is, quite literally, astronomical.

Unless, of course Xero, meets this high expectation and dramatically increases its earnings!

Long-term versus short-term

It’s safe to say that Warren Buffett would never buy into an overvalued company.

His approach is folksy and simple. He only picks stocks that appear to be trading for fair value. This means doing his homework diligently, then seeking out good purchases at a discount. And if he doesn’t find sufficient value, well, he just doesn’t commit.

Of course, a growth investor who’s hungry for yield might roll his eyes at this approach. He might click his tongue dismissively and say, ‘Who the heck cares about the P/E ratio, man? Buffett is too old-fashioned. He’s missed out on so many incredible tech stocks. His track record for the past 10 years has been lousy.’

Hmm. Harsh words.

Of course, Buffett *appears* to have missed out on the hottest tech stocks — Facebook [NASDAQ:FB], Netflix [NASDAQ:NFLX], Google [NASDAQ:GOOGL].

His only high-profile tech picks seem to be Apple [NASDAQ:AAPL] and Amazon [NASDAQ:AMZN] — but he bought into them quite late. In the grand scheme of things, that’s not nearly enough to allow his portfolio to keep pace with the S&P 500 or Nasdaq.

On the surface of it, this verdict seems to be damning.

But, still, should we be so quick to dismiss the Oracle of Omaha? Does this sly old fox actually know something that the youngsters are ignoring?

A question of risk

Deep down inside us, deep within our souls, we each have a weighing scale. It’s the one we subconsciously use, constantly measuring the equation between fear and greed.

Our evaluation goes like this:

- The lower the risk, the lower the reward.

- The higher the risk, the higher the reward.

All too often, emotion takes over. And we are drawn to the possibility of a higher reward. Which means taking on more risk. And sometimes, we misjudge that risk. And that’s when it backfires. Spectacularly.

This is exactly what happened with the dot-com bubble. Here’s what I previously said about that event:

We kind of take it for granted now. But remember: the internet was cutting-edge tech back in the ‘90s. It encouraged sweaty palms, racing hearts, and soaring imaginations. Through the wonders of dial-up modems and copper telephone wiring, anyone could connect to the World Wide Web. The potential seemed dizzying and endless.

Naturally enough, internet businesses exploded. Seemingly overnight, a flood of new companies went public. Some of these names are legendary, and chances are, you will feel a touch of nostalgia at the mention of them.

AOL. eBay. Yahoo. GeoCities. Excite. Lycos. Netscape…

The internet was boiling hot. And it created a feverish stampede as people snapped up shares in any dot-com company. Financial speculation became rampant, and confidence in this ‘new economy’ skyrocketed.

As a result, the Nasdaq index peaked in March 2000, hitting an astounding 5,047.62 points. The mood was jolly as employees and executives at dot-com companies became overnight millionaires. This juggernaut seemed unstoppable.

And then…it suddenly ran out of steam, and it all came crashing down in dramatic fashion.

I’m talking gasp-inducing and groan-worthy.

In October 2002, the Nasdaq plunged to 1,114 points, down 78% from its peak.

In the horrific aftermath, over 50% of internet companies collapsed, and fortunes were wiped out.

When the dot-com bubble burst, a lot of people were hurt. Badly. The devastation was total. But, amidst the rubble and ashes, one investor who didn’t feel the pain was Warren Buffett.

Why? Well, it’s because he had made it a point to steer clear of risky stocks. He eliminated any downside simply by exercising discipline and relying on common sense.

Buffett’s words ring true today just as it did back then: ‘Be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful.’

Of course, no one has a crystal ball. No one can say for sure when an optimistic bull market becomes a pessimistic bear market. But mental preparation is key.

The final analysis

Here at Wealth Morning, we don’t hide the fact that we’re value investors. And it’s not just P/E ratios that we’re looking at either. We want to understand debt levels, underlying assets, future direction, and a range of other fundamentals.

We aim to find wealth beyond the radar. That means studying the financial landscape, outlining the threats, and charting a path forward for you to take.

If you qualify as Wholesale or Eligible investor, we have a hands-on service to help you build a portfolio with these sort of opportunities. It’s called Vistafolio — and you can learn more about that here.

Forget tech bubbles. Forget following the crowd. Think for yourself. The best opportunities are those lying on the fringes on the mainstream. And we aim to show them to you…

Regards,

John Ling

Analyst, Wealth Morning

(This article is general in nature and should not be construed as any financial or investment advice. To obtain guidance for your specific situation, please seek independent financial advice.)

John is the Chief Investment Officer at Wealth Morning. His responsibilities include trading, client service, and compliance. He is an experienced investor and portfolio manager, trading both on his own account and assisting with high net-worth clients. In addition to contributing financial and geopolitical articles to this site, John is a bestselling author in his own right. His international thrillers have appeared on the USA Today and Amazon bestseller lists.