Just imagine.

Imagine, for a moment, if the Chinese and Russian navies decided to team up.

Imagine if they started putting together an armada of warships.

Imagine if they decided to cross the ocean and sail close to the continental United States.

Imagine if they did this on the friendly invitation of regional nations like Brazil, Argentina, and Mexico.

Imagine if the Chinese and Russians called this naval exercise ‘freedom of navigation’.

Imagine if their reason for doing this was to check American expansionism.

Imagine if they said they had historical proof of American aggression.

Imagine if they said that, until 1848, territories like Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, California, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, and Wyoming actually belonged to Mexico before America waged war and ‘stole’ them.

Imagine if they said that America was also a reckless and irresponsible global citizen — the 1918 influenza pandemic which killed millions actually started in Kansas, but was misnamed the Spanish flu in what is clearly a case of ‘fake news’.

Imagine if they said that a whistle-blower named Ron Paul has ‘revealed’ that America has over 900 military bases worldwide in 130 countries.

Imagine if China and Russia claimed they had no choice to enforce ‘international rule of law’ to keep America contained for the sake of global peace and stability.

Well, just imagine.

So how does the United States react to all this? Kindly? With good humour? With a smile and a wave?

Hell, no.

Quite the opposite.

America finds itself backed into a corner. Angry. Seething. Desperate.

‘The Chinese and Russians are hypocrites and liars. They’re just finding a reason to box us in and attack us.’

And just like that, America now has to consider striking back.

Understand your enemy

You don’t need to like China — or even Russia, for that matter.

You are welcome to hate them, fear them, and maybe even want to destroy them.

That’s completely understandable — and possibly justified, depending on what your priorities are.

But before you move forward with any concrete action, it’s important to have a sense of your enemy’s worldview — and more importantly, how they perceive you.

Chris Voss, a former FBI negotiator who runs popular courses on the subject, makes the distinction between empathy and sympathy.

- Empathy means understanding what is driving your opponent emotionally.

- Sympathy means approving of your opponent’s ideology.

In business and in war, having empathy is critical. It means putting yourself in the other fella’s shoes. It means understanding the pressure points and the pain points. Then seeing how you can work with that.

Now, again, that doesn’t necessarily mean that you approve and support the other guy’s actions. It just means that you understand it.

All too often, there’s a tendency for us to moralise. We use words like ‘right’ and ‘wrong, ‘good’ and ‘evil’ a lot. This is especially true when we feel like we need to justify *our* point of view. This binary distinction gives us comfort as well — ‘If I’m right, therefore the other side must be wrong.’

But remember this: in the eyes of your opponent, perceptions are flipped in reverse. He sees himself as being the hero of his own story, while he thinks you are the villain. He’s locked into his cultural bias, just as surely as you are locked into yours.

Try walking a mile in their shoes

Clint Eastwood, the legendary actor and director, demonstrated this theme perfectly.

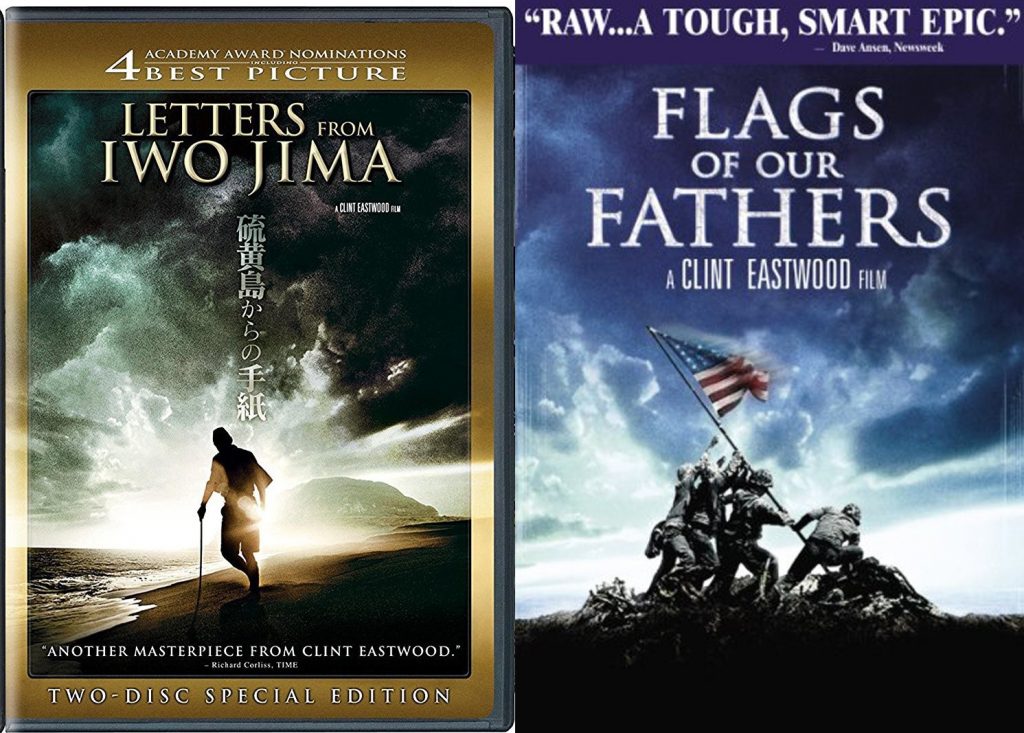

In 2006, he released two monumental World War II films:

- In Letters from Iwo Jima, he covered the Battle of Iwo Jima from the Japanese point of view.

- In Flags of Our Fathers, he covered the exact same event from the American point of view.

Source: Amazon

While watching these movies back-to-back, you can’t help but be struck by the stark disconnect between the two sides.

During the battle itself, the Japanese see the Americans as savage and mysterious. Not quite human. Likewise, the Americans see the Japanese in much the same way.

The fighting is bloody and fuelled by prejudice. Both sides are consumed by fear and desperation.

Moments of humanity are few and far between — but when they do happen, the emotional power is undeniable.

In one memorable scene, a Japanese officer named Colonel Baron Takeichi Nishi picks up a letter from a dead US Marine. Nishi is no ordinary Japanese. He is an aristocrat, and he is fluent in English. He’s spent time living in the United States, even competing as an equestrian show jumper at the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics. His social circle of friends include Charlie Chaplain, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks.

Nishi understands American culture intimately — and he knows that there’s more to the gaijin enemy than just simplistic propaganda and stereotypes.

So, to make a point, Nishi reads the dead Marine’s letter out loud, translating from English into Japanese for the benefit of his platoon.

The message is poignant. A mother from Oklahoma writing to her son:

‘Sam, I have mailed you a couple of books to read. I hope that you like them. Yesterday, the dogs dug a hole under the fence. They ran all over the neighbourhood. By the time we found them, the Harrisons’ roosters were terrorised. Don’t worry about us. Just take care of yourself and come back safely. Remember what I said to you. Always do what is right because it is right. I pray for a speedy end to the war and your safe return. Love, Mom.’

A stunned silence falls over the Japanese platoon. There’s a mutual recognition. Sam’s mom could be their mom.

The implication is clear: the enemy isn’t so different from them.

It’s all a matter of perspective.

Today’s problem with China

As I noted in my previous article on the issue of American values versus Chinese values, the fundamental challenge today is to understand how the two cultures approach foreign policy.

Americans, by nature, are optimistic. Chinese, by nature, are anxious.

Glass half-full. Glass half-empty.

If geography is destiny, then it’s clear that the American empire is incredibly blessed. It has rarely experienced famine — and an abundance of resources has given it momentum to expand with idealistic ambition.

By comparison, the Chinese empire has had a rough ride. In a 2,000-year stretch, it has experienced no fewer than 1,800 famines. That’s about one famine a year, running across centuries and generations. Chinese expansion is less about idealism and more about desperation.

Yet these cultural nuances and subtleties can be lost, especially when the mainstream media decides to go for broad strokes.

You see it in today’s sensationalist coverage:

- The Chinese media paints America as arrogant and ignorant. They perpetuate the stereotype of the Ugly American.

- The American media paints China as greedy and cunning. They perpetuate the stereotype of the Yellow Peril.

Source: The Conversation

Every conflict must begin with dehumanising the enemy.

They are portrayed as alien, antagonistic, and immoral.

Simplifications are, of course, necessary when you are trying to build a storyline.

Carl Von Clausewitz, the great Prussian strategist, said: ‘War is not an independent phenomenon, but the continuation of politics by different means.’

But, often, simplifications and stereotypes do more harm than good.

If America must confront China and draw blood — possibly over the fate of Taiwan — then it should do so with a deeper understanding of what drives Chinese hopes and fears.

Let’s face it: war is a complex and messy business (as the occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan have demonstrated). To embark upon it without careful calculation would be disastrous.

In the words of military strategist Sun Tzu:

‘To know your enemy, you must become your enemy. If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle.’

Yes, empathy is essential, not optional.

Now, as financial analysts, we are cautiously watching these developments unfold.

Is armed conflict looming? Could America and China actually clash? Will Australia and New Zealand be dragged into this?

With tensions reaching boiling point, it’s never been more important to manage your risk. Consider your exposure. Could it be prudent to have investment holdings outside the Asia-Pacific region?

Our Quantum Wealth Investor programme can offer you critical insights here.

Of course, past performance is no guarantee of the future, but here are some of the trends we’re watching:

- Property

- Infrastructure

- Energy

- Healthcare

- Technology

👉 Sign up for our premium research for these opportunities and many more under the radar.

Our diversified global strategy could serve to protect your wealth and give you passive income during these dizzying times.

Regards,

John Ling

Analyst, Wealth Morning

John is the Chief Investment Officer at Wealth Morning. His responsibilities include trading, client service, and compliance. He is an experienced investor and portfolio manager, trading both on his own account and assisting with high net-worth clients. In addition to contributing financial and geopolitical articles to this site, John is a bestselling author in his own right. His international thrillers have appeared on the USA Today and Amazon bestseller lists.