August 2000: IMF Report contends Irish property prices are almost certainly heading for a collapse in the medium-term.

Between 2007 to 2013: Irish house prices (nominal) fall 54%.

March 2021: IMF Report contends New Zealand’s unsustainable house price rises could trigger a pronounced correction.

April 2021: New Zealand house prices up 16.1% in a year.

A ‘ghost estate’ of unoccupied homes in Ireland circa 2010. Even buoyant housing markets can change quickly. Source: Daily Mail

At a recent event in Auckland, I remonstrated that house prices could slide. It may not seem possible, but it is. You could have felt the perspiration dampen the room. As I provided an uncannily similar series of events in the mirror of history, the mood began to darken.

You see, when people’s hope is built on a beneficial pile they are invested in — and you point out that pile could reduce, you risk their aversion. Not because you may be right or wrong, but because you are dashing hopes in something they rely on to be true: That property prices will keep going up.

Wealth Morning does not exist to toe the line. We are here to challenge assumptions, provide warnings, and find opportunities beyond the radar.

The trite disclaimer that ‘past performance does not provide a guide to future performance’ is not entirely correct. It may apply to fund management returns over, say, a decade. But past performance over a much longer period — I’m talking 40 years or more — could provide signs.

Property prices have been shooting up. Because debt is cheap, supply is short, cashed-up migrant money is still evident, and high sale prices support the momentum. I will show you, in a moment, how these conditions can change on a dime and pull the rug from under you.

Look, it’s our job to point out risk factors. We may not be right. But if, in our view, we see a child about to get hit by a bus, we will shout.

Yet property, at least here in New Zealand, should always find some underlying support. It is another emerging asset class that may be looking more and more unsteady…

Bitcoin

‘You’re a sharemarket investor. What do you know about cryptocurrency?’

You may well ask this. And I will tell you I worked for the world’s first regulated Bitcoin fund in Europe for over a year. I understand that sophisticated investors can make money on Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. Because they are volatile.

But when you analyse the asset, you find support for the price to be flimsy.

- No supporting assets.

- No guarantee from a respected government.

- Competition from 5,000 other cryptocurrencies.

- Threat of regulation over concerns of widespread financing of illicit transactions.

- An alternative digital payment system under discussion by the US Federal Reserve.

- Climate change concerns: Bitcoin mining activity has an annual carbon footprint equal to New Zealand.

As an investor, I might buy Bitcoin if I could see a path for it to go from around 50k to 200k within a year. A 150k profit could cover the potential risk of near-total loss of my 50k. So you see the stakes.

But I do not see Bitcoin at 200k next year. Frankly, there are more risk-managed investments with attractive upside out there. Where the potential gain does not come with such heady downside.

It is all about pricing risk.

Is it worth it?

Often, when you run the ruler, it is not.

Property

‘You’re a sharemarket investor. You have a vested interest in seeing property slide!’

We do, in part. As residential property investment has become more challenging, our enquiry rate is up. For many people, there are simpler ways now to seek income and potential growth.

But this is not the whole story. We are also property owners and investors. And we still see attractions in the asset class, particularly with commercial property. So much so that many of the shares we analyse are based on property assets.

My sense of the risk currently on residential property begins with my memory as a kid in the 1980s. Actually being unable to sell a house. Having to rent it to a chain-smoking, deep-fat frying family from England to move on.

Then, after more than a year, seeing my parents get next to nothing for it.

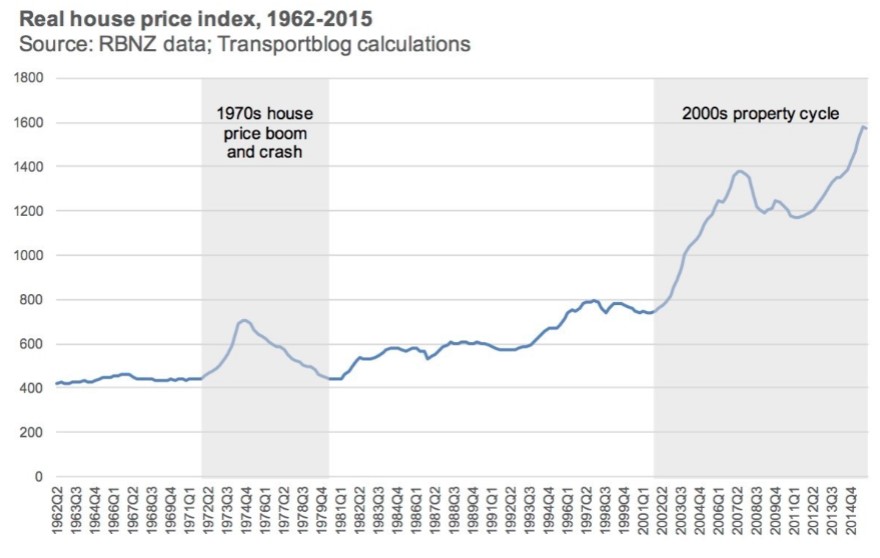

In the late 1970s in New Zealand, house prices fell around 40% in real terms. In fact, it was a lost decade, with homes being worth no more at the end than they were at the start.

The run-up we saw from 1971 to 1974 has eerie similarities to the longer 2011 to 2021 build-up. It was based on high net migration and shortages of builders and materials.

Muldoon’s government became alarmed then, as Ardern’s one seems to be now. Planning controls were loosened to allow more flats to be built in cities. My neighbourhood is testament to this. Historic villas subdivided with 1970s units behind.

Even more compelling is the example of the Roaring Twenties. An economic boom period following the last world pandemic — the Spanish Flu — and heavy ‘money printing’ stemming from World War I. Pent-up demand and low interest rates fed raging asset prices. Manhattan real estate reached its all-time high in 1929, as did stocks across the New York Stock Exchange.

Then came the unravelling.

By 1932, Manhattan real-estate prices had fallen 67%. They did not fully recover until the 1960s.

The stock market lost more than 80% of its value from its 1929 high to its mid-1932 low.

In this case, the potential advantage of more liquid assets came to pass.

By 1936, stocks had in real terms fully recovered. They went on to outperform property growth by a factor of 5.2 between 1920-1939.

Of course, this discussion is speculative. The Roaring 1920s are very different from the Roaring 2020s.

Yet, if we look at other more recent bubbles a century later, we see some similarities here in New Zealand.

The Irish property bubble

- In August 2000, the IMF warned that Irish property prices were almost certainly heading for a collapse in the medium-term.

- Between 2007 to 2013, Irish house prices (nominal) fell 54%.

- In March 2021, the IMF warned that ‘New Zealand’s unsustainable house price rises could trigger a pronounced correction’.

Yet there is a key point of difference.

Ireland in the 2000s was outbuilding demand. About 75,000 units were being built each year for a similar population size to New Zealand. By one estimation, about 12% of the workforce was engaged in construction.

In New Zealand, annual figures last year were just under 40,000 homes built. We’d need to see at least a 50% increase to get into Irish over-building territory.

The more likely source of risk here comes down to leverage. As it so often does.

When Ireland joined the European Union in 1999, it soon come to enjoy much lower interest rates than before. People were encouraged to take on debt to get into homes. Property was seen as a guaranteed bet, and mortgage debt exploded.

Household debt-to-GDP rates in Ireland reached very high levels, as we see today in New Zealand.

Interest rates in New Zealand now sit around their lowest levels ever. And the mortgage brokers we speak to routinely see DTIs (debt-to-income ratios) of 6x.

Ireland, in contrast, has learnt hard lessons in more recent times. And today, most residential lending in Ireland is restricted by the Central Bank to a DTI of 3.5x.

The Central Bank of Ireland refers to this as the Loan to Income limit:

‘The LTI limit restricts the amount of money you can borrow to a maximum of 3.5 times your gross income. So, for example, a couple with a combined income of €100,000 you can borrow up to a maximum of €350,000.’

It would appear the most significant risk to New Zealand property is the re-pricing or restricting of lending.

Interest deductibility rules have already re-priced loans to property investors. But the greater risk is the introduction of DTIs and inflation.

Inflation is now so evident in New Zealand it is hard to see interest rates staying low forever.

There are clear lessons from Ireland. And also Spain. You can out-build the market. And high leverage can, in the end, haemorrhage prices.

I do not see New Zealand out-building its supply gap any time soon. But I do see a lot more activity than before coupled with a twisted greed and fear gap, a debt bomb, and growing regulation.

In this regard, the ghost of Muldoon could well come to sit in auction rooms across Auckland. Especially for investor-focused residential properties.

The markets

Of course, many speculative stocks raise the same concerns in the financial markets.

Advisers will say you need to diversify. Which neutralises returns across the board and denies outperformance from a smaller number but still diversified set of high-conviction opportunities.

For those, you need to go back to assessing value. Price is what you pay. Value is what you get. A good investment should have a clear measurement of underlying value. And a view on how its price is really supported.

The key to identifying a bubble is to identify a lack of price support.

Markets are complex. But right now, we are seeing old support get shakier.

Regards,

Simon Angelo

Editor, Wealth Morning

This article is general in nature and should not be construed as any financial or investment advice. To obtain advice for your specific situation, please consult an Authorised Financial Adviser. The author is involved in portfolio management for Wholesale and Eligible Investors via Wealth Morning’s Vistafolio Managed Account Service.

Simon is the Chief Executive Officer and Publisher at Wealth Morning. He has been investing in the markets since he was 17. He recently spent a couple of years working in the hedge-fund industry in Europe. Before this, he owned an award-winning professional-services business and online-learning company in Auckland for 20 years. He has completed the Certificate in Discretionary Investment Management from the Personal Finance Society (UK), has written a bestselling book, and manages global share portfolios.