Do you remember how things looked back in the early ‘90s?

The Cold War was over. The Soviet Union was shattered. The United States was ascendant in its role as the world’s only superpower.

There was so much optimism. Walls and borders were coming down. Free trade was beginning to flourish. It felt like anything was possible.

The fall of the Berlin Wall. Source: New York Times

Francis Fukuyama, the American political scientist, called this point ‘The End of History’. He believed that all of humanity’s struggles had finally led us to this moment of moments. The answer was profound, and it was staring at us right in the face — Western-style liberal democracy would serve as the final form of government.

How could it not be? This was the sanest, most logical choice. From Moscow to Johannesburg to Sydney, the transformation was inevitable. We were now free to participate in what George H. W. Bush and Mikhail Gorbachev called a New World Order.

Forget the usual limits of nationality, ethnicity, or religion. Prosperity and happiness were firmly within your grasp. You only needed to dream and work for it.

In this era, international relations would be defined by three key features:

- Cooperation, not competition, between countries.

- The United States would act as the world’s policeman.

- The United Nations would act as the world’s judge and jury.

This felt clean and simple. Our circle of life was complete. Or…was it?

From utopia to dystopia

So…here we are now. It’s 2020. The dawn of a brand-new decade. And the situation on the ground is actually looking a lot messier than we thought it would be.

The COVID-19 pandemic has crippled trade. Barriers are going up. And the globalist dream appears to be crumbling under the weight of resurgent nationalism.

Border wall in Mexico. Source: Washington Post

Transnational groups like the European Union and the World Trade Organization — once considered the darlings of globalism — are now increasingly under siege. Worse still, America’s superpower status is being threatened by a rising China.

Scepticism seem to be the rule of the day now. Nerves are frayed. Markets are jittery. Everyone is angry — at quarantine lockdowns, at entrenched bureaucracy, maybe even at Western liberal identity itself.

How did we go from the edge of utopia to potential dystopia? Are we seeing the destruction of everything that’s come before? What’s at stake here?

Problem #1: The end of Pax Americana

The 21st century was meant to be a continuation of Pax Americana — an American-led peace defined by neoliberal values.

This era would be enforced by negotiation and regulation. And, if that failed, by using the sharp end of the stick.

Former US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright summed it up best:

‘If we have to use force, it is because we are America; we are the indispensable nation. We stand tall and we see further than other countries into the future.’

This brand of American exceptionalism has been followed by successive presidents, which is why over 700 military bases have mushroomed around the globe. Armoured divisions. Carrier strike groups. Special operations forces. All ready for kinetic action at a moment’s notice.

This forward strategy is born out of a classical Latin philosophy: ‘Si vis pacem, para bellum.’ Which means: ‘If you want peace, prepare for war.’

Under the right conditions, this foreign policy has led to positive results.

Consider this: the metamorphosis of Japan and Germany from fascist pariahs during World War Two into the democratic industrial powers we know today. Would this have happened if not for America acting as the ultimate guarantor of peace and security?

Another example: South Korea. Its very existence today as a prosperous nation is a testament of a Pax Americana. For it was American power that beat back North Korean aggression and kept it in check for decades.

Time and again, even the most liberal doves among us have to admit: yes, sometimes, strength of arms is exactly what’s needed. For lack of a better option, it does help to build a better future. History pays witness to this.

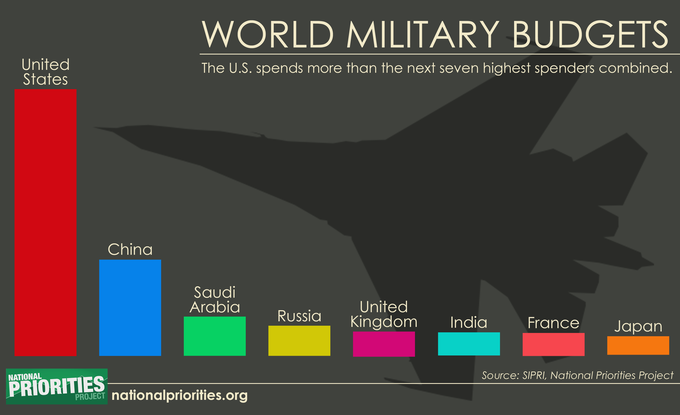

Yet, running an empire in this fashion does come with a heavy price tag. America spends more on its military than the next seven nations combined.

Such full-spectrum dominance deters any enemy from engaging in full hostility with America. But, at the same time, it creates a unique problem — American policymakers have become habitual in their use of military power to pre-empt threats.

Jeremy Scahill, in his book and documentary Dirty Wars, makes this point:

‘We have created one hell of a hammer. And for the rest of our generation…this force will be continually searching for a nail.’

And as time has gone on, it has become increasingly clear that there’s only so much you can solve by hammering nails. This is especially true in a 21st century marked by asymmetric conflict that is far removed from the total war we experienced in the 20th century.

The turning point here has to be Iraq. The successful invasion and occupation of the country unfolded in a record three weeks. It made for fantastic television — real-time combat that we followed beat-by-beat, through the lens of embedded reporters.

Who can forget that ‘Mission Accomplished’ moment? George W. Bush landed on the deck of an aircraft carrier, and amidst cheering sailors, he declared an end to major combat operations in Iraq. It was a wholehearted embrace of destiny.

All this was good optics at the time. But, as we now know, the mission was far from accomplished. We saw the rise of a terrifying insurgency. Sectarian violence exploded between Sunnis, Shiites, and Kurds. And ISIS was born, a fanatical response to the power vacuum.

The price that America has paid in terms of blood and treasure can be calculated in dollar terms. But the damage done to American prestige is still unravelling.

Also, a stone’s throw away, we have Afghanistan. At 18 years and counting, it is America’s longest war. An exhausting odyssey of fighting for rugged valleys and jagged mountaintops. The Taliban, through fierce tribal tenacity, has succeeded in wearing down American resolve. The desire to leave is now stronger than the desire to stay.

The unthinkable has already happened — as America downsizes its presence on the ground, it has signed a peace treaty with the Taliban, thereby abandoning the Afghan people to their fate.

Nation-building — as we saw it happen in Germany, Japan, and South Korea — has completely faltered in the 21st century. There have been no success stories; merely a string of failures.

This serves as the rudest possible rebuke of Pax Americana. If the world’s strongest fighting force cannot tame the Middle East, well, who can?

Problem #2: Anger on the home front

Here’s a sombre fact: most Americans still struggle to find Iraq and Afghanistan on the world map, despite the public nature of those Bush-era wars. They fare even poorer when trying to pinpoint where the Obama administration has waged other shadowy interventions in Pakistan or Somalia.

What the liberal and conservative media has often strained to do — with mixed success — is justify the need for America’s military adventures abroad.

Left-wingers often choose to frame their mission in humanitarian terms, while right-wingers focus on existential threats. Historically, the tempo for war has been a constant feature under both Democratic and Republican administrations.

But, this time, something is different. The American appetite for foreign interventions has declined sharply. Long gone is the patriotic fervour we saw in 2003, replaced now by an uncharacteristic pessimism and world-weariness.

There’s no getting around this prickly domestic issue: COVID-19 is a game changer. For the average American Joe who’s just lost his blue-collar factory job in a Rust Belt state like Ohio, why should he care about what’s happening in a tribal village on the borders of Pakistan? Why indeed? For him, there’s a much more pressing need: paying the bills and putting food on the table.

By 2030, it is predicted that over 20 million jobs worldwide will be lost to robotics. This is to say nothing of the millions more that will become obsolete as a result of further restructuring.

And even for the lucky few who still manage to find jobs, the future looks bleak. All they might be able to expect is a ‘McJob’ — a lowly-paid position with no prospects for future advancement.

All this is symptomatic of a digitised ‘gig economy’ that is pushing down wages, championing short-term contracts, and demolishing long-term security.

There was once a time when you could work comfortably at a single company your entire life and be rewarded for it. But that’s just a picture-perfect memory now. It no longer exists. It’s gone. Extinguished. Like smoke in the wind.

Increasingly, there is a gulf between what policymakers in Washington want to pursue versus what the average citizen in the heartland wants domestically.

Job security is a clear and present fear that many Americans feel deep in their bones, gnawing away at them, causing sleepless nights.

Why should we care about policing the world when we can’t even feed and clothe ourselves at home?

Problem #3: The rise of populism

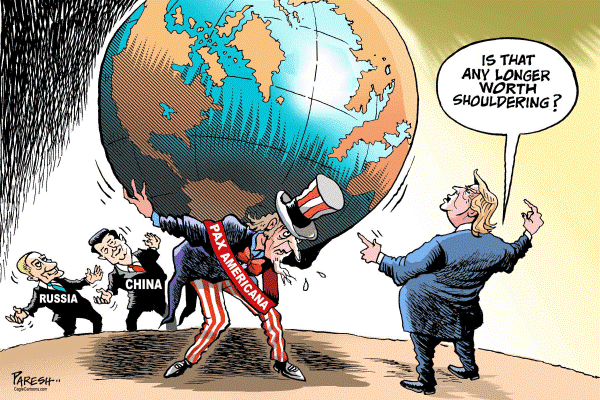

There’s no getting around the fact that Donald Trump is a new kind of president. He’s blunt, he’s brash, he’s populist. He cares not for the usual etiquette of Pax Americana. At times, he looks like he’s hellbent on smashing it into pieces.

Source: Cagle Cartoons

What does Trump stand for? Well, broadly speaking, three things:

- Isolationism — the rest of the world should be kept at arm’s-length.

- Nativism — the born-and-bred American has more rights than anyone else.

- Zero-sum — for America to win, it must concede as little as possible.

Trump is openly dismissive of neoliberal ideas. And he scoffs at America’s moral responsibility to police the world.

For this reason, he’s broken with tradition, questioning everything from military alliances (‘Germany is not paying their fair share’) to free-trade deals (‘China is laughing at us’) to border control (‘When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best’).

Forget international diplomacy with its civilised double-speak. Trump intends to tear up the rulebook entirely and write a new one.

In this way, you could say that Trump has much more in common with the robber barons of the 19th century — Carnegie, Vanderbilt, Rockefeller — than he does with any president in living memory.

This has delighted Trump’s supporters so far, and all things being held equal, they may just give him a second term in the White House. And, gosh, who can blame them?

What the future looks like

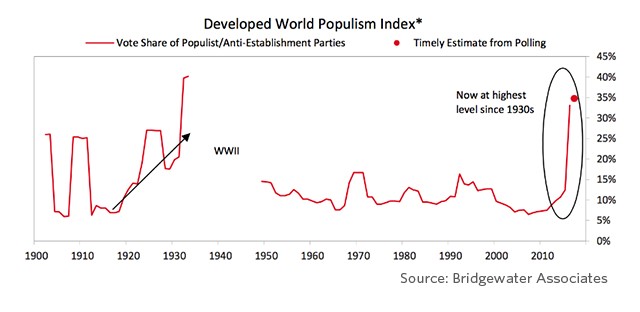

History doesn’t necessarily move in a straight line, as Francis Fukuyama claimed. Rather, it tends to move in cycles.

Source: MarketWatch

Source: MarketWatch

Right now, as countries retreat into themselves, we’re seeing a sudden surge in populism. It’s happening at a rate that we haven’t seen since the beginning of the Second World War.

If the current mood is anything to go by, the globalist dream as championed by past American administrations may well be dead. It’s been replaced now by a keen desire to enforce hard borders and regain nationalist identity.

This conversation is still ongoing. It’s anyone’s guess how it will eventually turn out. The 21st century is still young, and much more could still unfold in the decades ahead…

Regards,

John Ling

Analyst, Wealth Morning

PS: Even in this era of isolationist politics, there are still exciting opportunities to be found around the world. Our Lifetime Wealth Investor programme will give you cutting-edge research on 20 of the best global stocks around, delivered weekly.

John is the Chief Investment Officer at Wealth Morning. His responsibilities include trading, client service, and compliance. He is an experienced investor and portfolio manager, trading both on his own account and assisting with high net-worth clients. In addition to contributing financial and geopolitical articles to this site, John is a bestselling author in his own right. His international thrillers have appeared on the USA Today and Amazon bestseller lists.