If you’ve been around markets long enough, you’ll know something frightening. Yet often ignored. They can fundamentally price assets wrong.

When that happens, the bubble can burst. And the pain of a deep correction follows.

We could be here again. In one of the most important markets in this country. And another globally. I’ll come to those in just a moment.

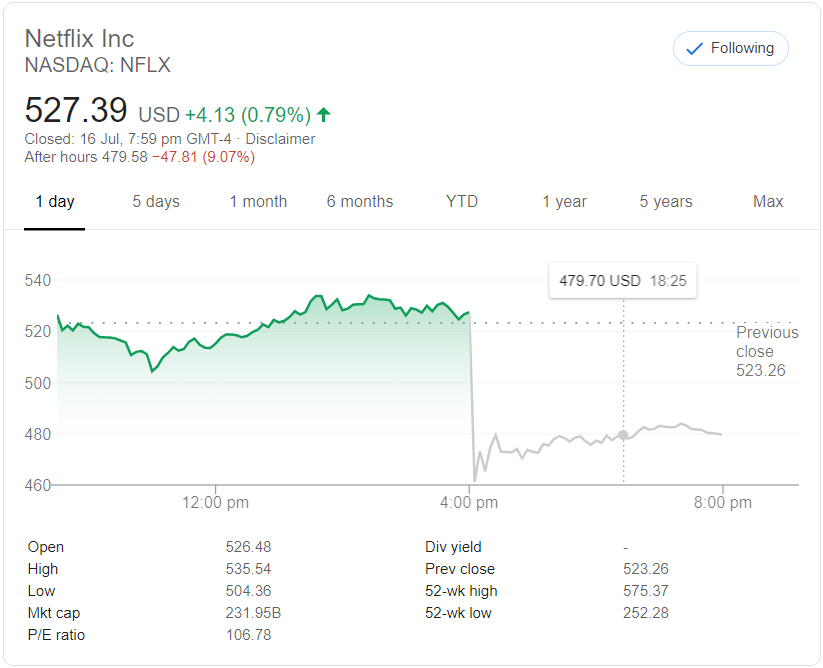

From the 1990s to 2000, there was intense interest in the new technology of the internet. And the business opportunities it presented. From 1995 to 2000, the NASDAQ rose 400%. By 2002, it had lost 78% of its value.

Source: Wikipedia

This shocking turn of the market came to be known as the ‘dot-com crash’. And if you look back at the companies that led the cliff fall, they have one thing in common.

The fundamentals were out of whack. P/E (price-to-earnings multiples) sat at a stratospheric level. For example, in 2000, Cisco [NASDAQ:CSCO] had a P/E over 100.

That company has never again reached its March 2000 high near USD $80. These days, it trades around $45, with a P/E about 18.

New Zealand investors will know this phenomenon very well. This country got hurt more than most by the earlier 1987 market crash. The lead-up to that? Many businesses with uncertain futures and very high P/E ratios were the market darlings.

So why do investors still buy stocks at such high prices?

They are factoring in rapid growth.

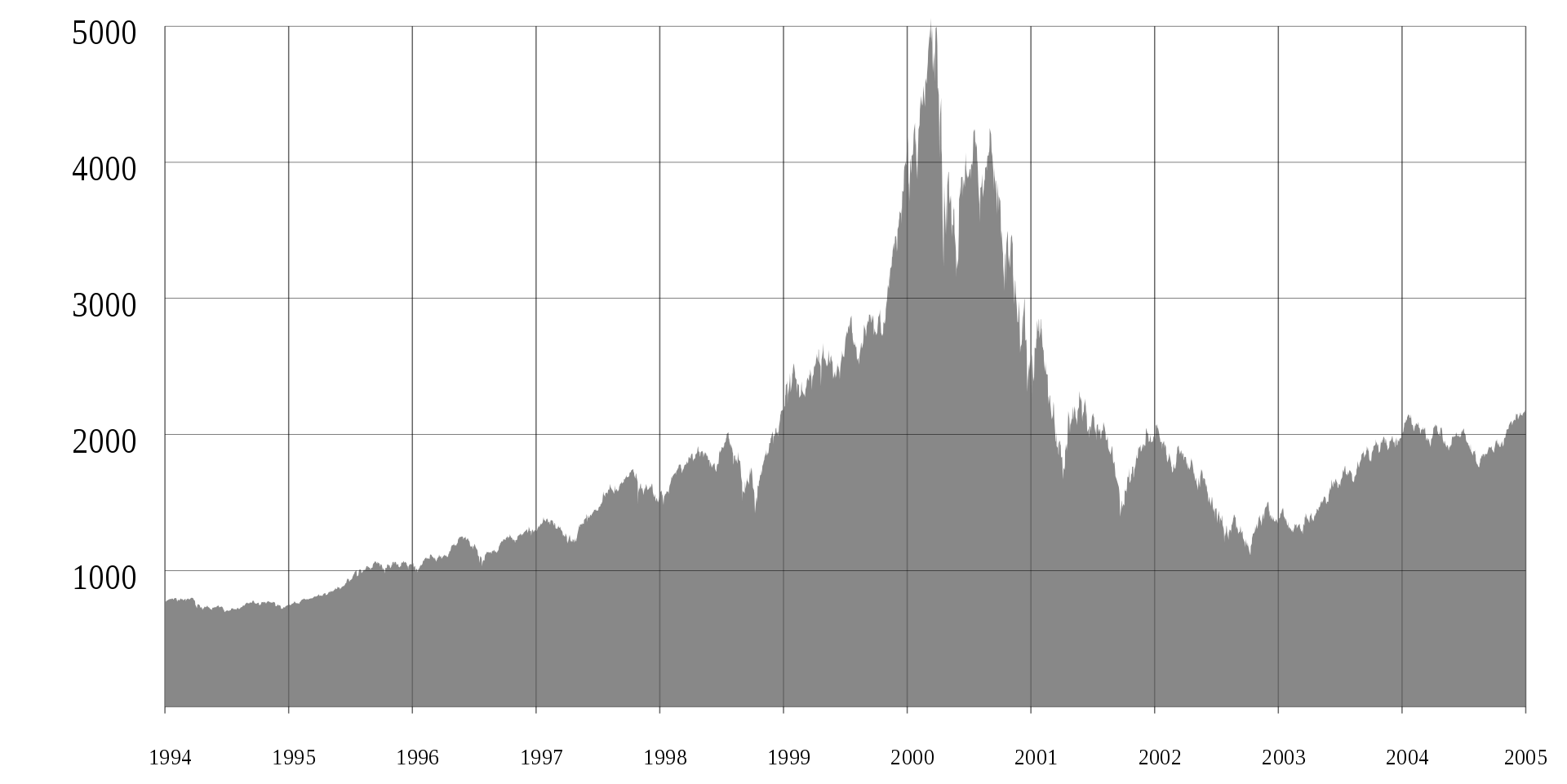

Take a look at Netflix [NASDAQ:NFLX]:

Source: Google Finance

It’s a growth story. P/E over 100. Banking on constantly growing subscriber numbers creating an ever more valuable business.

As you can see from the above graph, when subscriber numbers came in lower than expected — as I write — the price is in for a heavy fall.

We all want a growth company. We’re constantly on the lookout for them. But I am now very circumspect on some of the P/E ratios I see on tech stocks.

In our Lifetime Wealth Investor research, we aim to find subscribers value for long-run growth. And we’re seeing that less in internet and software tech, and more in other sectors like health, biosciences, and material extraction.

You can subscribe for our latest value picks in our Premium Research here.

The New Zealand housing market

Time and time again, I’ve been proved wrong. But I still can’t help point out that this market has to be — in many sectors — fundamentally overvalued.

Take a look at the median Auckland house:

| Median price (June 2020): | $928,000 |

| Median household income: | $98,291 |

| Price-to-income multiple: | 9.44 |

| Gross rental yield (March 2020 – Avondale): | 3.70% |

| Net rental yield (assume 30% costs): | 2.59% |

| Fundamental value: | $590,000 |

For the fundamental value, I’ve taken into account some key alternatives. In 2019, the NZX50 delivered an average dividend yield of 4.54%. Which is essentially the gross yield.

If we were to require this gross from the median Auckland house, it would be worth around $756k. If net, only around $530k.

Finally, consider a government bold enough to attack the supply and debt issues needed. This could push Auckland housing more toward the lower end of Demographia’s ‘severely-unaffordable’ benchmark. ‘5.1 and over median multiple income.’

Let’s say they can reach 6x. In which case, a median price around $590k. Discounting yield for some growth, this may be a closer estimate of value supported by fundamentals.

But housing is also an asset facing inelastic demand. Meaning people buy it for non-investment reasons. For shelter. For a pleasing place to live.

What’s going to happen?

Out-of-step fundamentals can last a long time. But not forever. Will September be that moment? When we face a COVID-battered, closed economy without wage subsidies?

I’m not sure about that. The money presses are still rolling. But, as an investor, it can pay to remain very wary when value gets out of step with reality.

Regards,

Simon Angelo

Editor, WealthMorning

Simon is the Chief Executive Officer and Publisher at Wealth Morning. He has been investing in the markets since he was 17. He recently spent a couple of years working in the hedge-fund industry in Europe. Before this, he owned an award-winning professional-services business and online-learning company in Auckland for 20 years. He has completed the Certificate in Discretionary Investment Management from the Personal Finance Society (UK), has written a bestselling book, and manages global share portfolios.