Most of my work is behind a screen. Trading or writing. I enjoy that. But there’s something missing. I’d like more time outside working with real things. So I’m looking to invest in a vineyard business, amongst other opportunities.

This goes beyond the financial assets of shares. It’s owning a piece of land that is part of a real business. Crushing grapes. Selling them to wineries. Seeing a finished and bottled product.

Clos d’Ambonnay’s small walled vineyard produces a Pinot Noir that sells for around $3,000 a bottle.

Source: Crush Wine & Spirits

My first glass of wine came from a cardboard carton at a university party. I don’t remember much of it. Probably for the best.

Some years later, I learned to appreciate a good wine food match. And this got solidified after living by the French coast. And routinely visiting nearby gastronomy centres.

But I’m hesitant about investing in wine as a business. I suspect magnetic, sunny businesses tend to come with premium prices. Which make them harder than others to get return from. Some may be a fool’s errand. Beware of any playground attractive to bored millionaires.

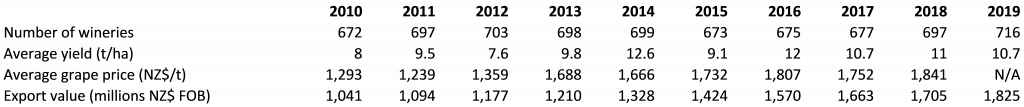

Despite the much-celebrated New Zealand wine industry, it contributed only $1.83 billion to exports last year. That’s only around 2.2% of total exports of $83.6 billion.

A hidden growth opportunity?

Now, while it may be easy to write wine off as a small industry in this country, the fact that it’s almost $2 billion and growing is still something worth a look at. And 2.2% of total exports is in a similar league to France, where wine exports of €14 billion are around 2.5% of their total exports of €555 billion.

Small land holdings with fine terroir can produce very valuable grapes. One of the world’s most expensive Pinot Noirs, Krug’s Clos d’Ambonnay, is produced on a walled plot in France of just 0.68 ha. It sells for more than $3,000 a bottle.

But, of course, there is very much that has to happen before grape reaches the bottle.

In New Zealand, at the production level, we’re seeing an average grape price of around $1,800 per tonne. Sauvignon Blanc is one of the most popular varietals, though Pinot Noir has been attracting premiums. And while we may not yet have any $3,000 bottles, I’ve seen some fine Waiheke Bordeux styles going for $300+.

The industry here has grown some 80% over the past decade by export value:

Source: New Zealand Winegrowers Annual Report 2019

Operating profit per hectare in the largest region — Marlborough — was around $8,700 per hectare in 2019. This compares very favourably to other farming enterprises. For example, dairying in Taranaki saw around $2,200 per hectare in a similar period.

For those interested in investing in the industry, there are direct, managed and market-listed options. Let’s take a look.

Vineyard leasing

As an investor, I’m assuming you’re not wanting to run your own wine business. Vineyards are essentially farms. Even a small farm can require extensive work, making an economic return challenging. There are many costs. Staff, pest, and disease monitoring, as well as irrigation, vine nutrition, pruning, bud rubbing, thinning, positioning, and bird control. Before you get anywhere near harvest and revenue.

Perhaps you simply want to walk the vines on land you own, do some occasional ride-on mowing, and collect revenue?

A few years ago, vineyard leasing was an appealing option. You bought a piece of land in wine country with good terroir and could lease it out to a vineyard operator at a return of around 7% on a ‘5 and 5’ agreement. A five-year lease with five years right of renewal at the end of it.

Per hectare, vineyard land prices have been increasing. As have the supply of grapes. This appears to have made yield on lease arrangements — particularly for smaller holdings — much more challenging and uncertain.

Managed investment

Another option is to invest in a syndicate-type arrangement to own a vineyard. You can see it managed and enjoy the financial returns from it. These offers are usually only available to wholesale or eligible investors who must qualify by size or experience.

In the midst of a pandemic, the world demand for New Zealand wine may now be less certain. So the risk profile on such investments has likely increased.

Tangible NZ and My Farm Investments are two such offers currently in the marketplace. They have minimum investment sizes varying from $100,000 to over $500,000.

While these situations tend to forecast attractive yields, in my view, there’s a significant drawback. Lack of diversification. You are often investing in one specific property.

And since the investment is passive, with few of the tangible benefits of ownership — such as being able to build a house on your land near the vines — I am minded toward publicly listed companies.

Share market investment

Listed wine companies provide the benefit of reasonable dividend yield, diversification — often across multiple vineyards and export markets — plus economies of scale.

This also comes with all the checks and balances of a public company. Audited annual reports. Requirements to announce key events and any insider share transactions to the exchange. Analyst coverage.

One such local company is Delegat’s Group [NZX:DGL]. This well-regarded New Zealand wine group is the fourth largest producer here by litres sold. And is known for premium brands such as Oyster Bay.

The business has enjoyed steady growth with attractive net margins in recent years above 17%. Had you purchased Delegat’s shares just 3 years ago, you could have more than doubled your capital via growth and dividends.

Today, the business looks quite expensive, trading on a P/E over 20, with dividends below 2%. Fortunately, we have found other wine companies presenting stronger value. We started looking into one for subscribers of our Premium Research Newsletter on the 13th of May.

Well, next month, I am off downcountry. To look at some potential property investments and more. This pandemic has been a terrible crisis. But it also presents opportunity.

Is there opportunity in wine or something else? I’ll keep you posted.

Regards,

Simon Angelo

Editor, Wealth Morning

Simon is the Chief Executive Officer and Publisher at Wealth Morning. He has been investing in the markets since he was 17. He recently spent a couple of years working in the hedge-fund industry in Europe. Before this, he owned an award-winning professional-services business and online-learning company in Auckland for 20 years. He has completed the Certificate in Discretionary Investment Management from the Personal Finance Society (UK), has written a bestselling book, and manages global share portfolios.