It’s one of the main reasons people get investments wrong. One of the main reasons they choose the wrong shares. Or person. Or career direction.

When you’re looking at something complex, like a business or an economic situation, there will be a lot you just don’t know. No matter how much research you do.

So you take knowledge shortcuts. You look at how a company has performed in the past. Their ROE (return on equity). The margins on their products. The earnings ratio at the current share price. And other snapshots.

But you won’t know everything about the stock. There’s much that is unknown. Even long-standing insiders don’t know what the future holds. Markets can change. New competitors may enter. Regulations can change the playing field.

Gaining confidence

There’s nothing wrong in using shortcuts to make decisions. It’s efficient. By using the right shortcuts on top of experience and a shrewd eye for market behaviour, you can do very nicely.

You don’t need to know the entire inner workings of a company to see that it’s doing well, it’s undervalued, and it has prospects in the market.

For instance, I can enjoy a great family road trip without knowing the exact inner workings of my car engine. I understand the engine is relatively new. It has done below 70,000km. It’s turbocharged and was recently serviced. That’s enough to give me confidence it can get me to my destination — and perform responsively if needed.

Knowledge gap

The danger is going beyond factual shortcuts and making assumptions.

This is where you don’t have the supporting facts. So you assume to bridge the knowledge gap.

For example, you pass a gas station and decide not to fill up even though you’re on a quarter. You assume there will be another station soon. But you don’t know the road. You could be wrong. You could get stuck.

Most people get caught out by assumptions because they start over-diversifying. They spread themselves too thin, trying to do everything, trying to buy every stock that looks good.

Quality, not quantity

Instead of sticking to the facts and using factual shortcuts, assumptions become the basis of decision-making. Even though studies show that a concentrated but expert portfolio can produce better results.

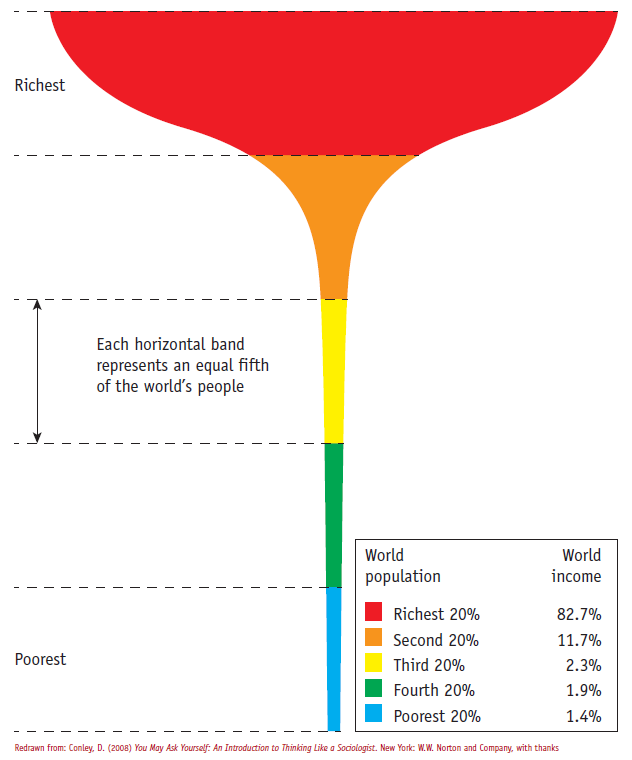

It’s the quality. Not the quantity. As Vilfredo Pareto’s principle has demonstrated, 80% of the desired result usually comes from just 20% of the drivers. In 1906, he showed that 80% of the land in Italy was owned by 20% of the population.

In 1992, the United Nations carried out the ‘champagne glass’ study, showing that 20% of the world’s population controlled 82.7% of the world’s income.

Wealth distribution

As investors and wealth generators, we want to make decisions that provide the highest returns.

This could mean cutting out 80% of the other options. Reducing quantity to find quality.

So often, it’s what you don’t do as much as what you do that counts.

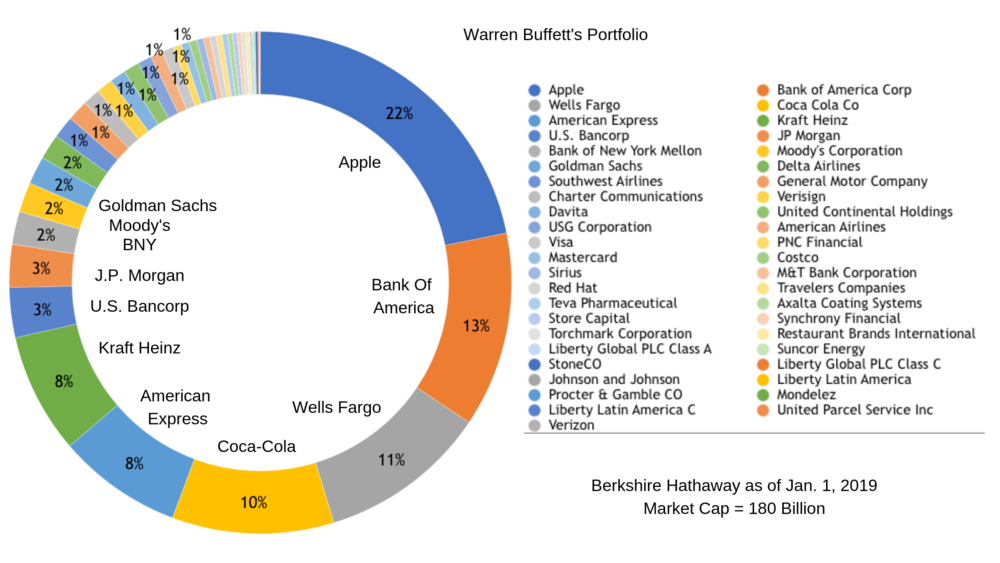

This thinking is behind the success of concentrated investors like Warren Buffet.

Take a look at Berkshire Hathaway’s portfolio as at 1 January 2019:

Source: Berkshire Hathaway

Just 8 holdings make up 78% of the portfolio.

This approach to simplification involves running a razor to slice off all but the best-quality options.

Buffett didn’t get them all right. He may have overpaid for Kraft Heinz [NYSE:KHC]. The stock has fallen heavily over the past year. The company is grappling with consumer diets shifting away from packaged foods — to whole and natural food producers.

But with a dividend yield of over 5% (at time of writing), Buffett may be able to wait out a strategy shift.

I’m a Kraft Heinz shareholder myself. They own Watties here in NZ. And I’m in agreement with him — it may not be time to either buy or sell.

This ‘cutting the carbs’ approach to enjoying the finest meat is a thinking principle encapsulated in a unique philosophy…

Occam’s razor

William of Ockham was a Franciscan friar doing some deep thinking in the 14th century. His logic has lasted more than 700 years, so I expect there is something in it.

‘When there exists different explanations — it is the one that requires the smallest number of assumptions that is usually correct.’

The more assumptions you have to make in reaching an explanation — the more unlikely it may be.

‘Never assume’ is a rule an old salesperson taught me years ago. Never assume anything about any prospect until you’ve got the facts.

Now, this is a great tool to apply to company research. What do you know for sure? And what are you assuming about the business and its opportunity?

Separate out the two. Slice off the eye fillet. Leave the rump for the passive-fund investors. And you’ll likely get the better cuts.

Now, you may say: ‘Well, under Occam’s razor, I’m making assumptions that certain businesses and/or the market will go up. Maybe I’m better not to invest at all? Stay in the bank?’

The trouble with this approach is you’ll end up missing out on asset growth.

About 200 years after Occam’s razor, a French mathematician and philosopher, Blaise Pascal, presented another argument. One I also live and invest by…

Pascal’s wager

This argument goes that, in many situations, we’re in an unavoidable wager.

When it comes to investing, you can either park your surplus in the bank or buy assets. By choosing one over the other, you’re making a bet on safekeeping versus risk and gain.

But once you have money, you’re in the game. You have to make a wager either way.

Pascal’s wager was related to faith. He argued that a rational person should seek to believe in God.

His reasoning: if God does not exist, a person who believes in God will have only a finite loss (perhaps some elicit pleasures).

But if God exists, that person stands to receive infinite gains (eternity in heaven) through believing and avoid infinite losses (eternity in hell).

This sort of wager can be applied to many questions around gain or loss.

When it comes to investing — or indeed in many critical decisions — consider the wager you’re making. And use the razor to cut out assumption-filled quantity in favour of fact-based quality.

Regards,

Simon Angelo

Editor, WealthMorning.com

Important disclosures

Simon Angelo owns shares in Kraft Heinz [NYSE:KHC] via Wealth Manager Vistafolio.

Simon is the Chief Executive Officer and Publisher at Wealth Morning. He has been investing in the markets since he was 17. He recently spent a couple of years working in the hedge-fund industry in Europe. Before this, he owned an award-winning professional-services business and online-learning company in Auckland for 20 years. He has completed the Certificate in Discretionary Investment Management from the Personal Finance Society (UK), has written a bestselling book, and manages global share portfolios.