When a friend of mine ran out of contract finance work in Jersey, she hopped across to another European city. There always seemed to be contracts there with one of the many multinationals that had chosen it as a base. And she’d come back to the island to see her husband on weekends.

Not an easy commute. But it can be tough in offshore finance.

Now, you’re probably thinking she hopped over to London on the 55-minute flight to Gatwick. No, she went to another city in a smaller country.

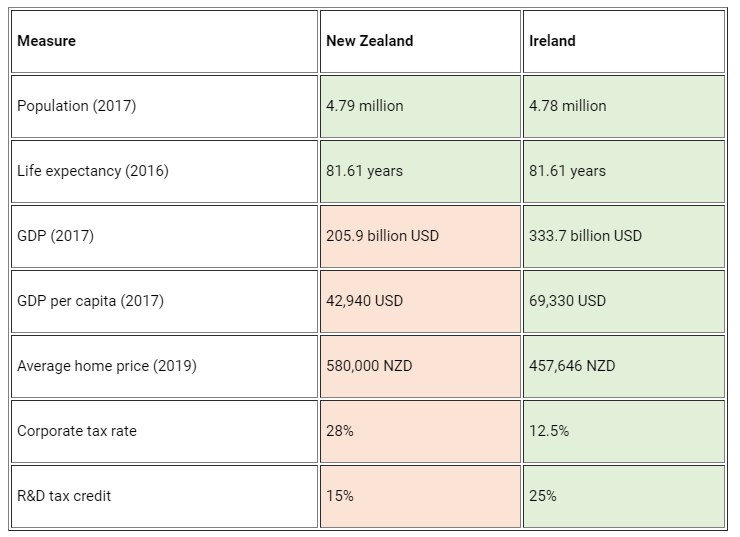

New Zealand has about the same population as this small European country. Yet this country’s GDP is nearly 63% higher.

From the mid-1990s onward, this country embraced the sort of foreign direct investment (FDI) that New Zealand missed.

While New Zealand attracted passive capital via selling houses and attracting wealthy migrants, this country pinpointed an opportunity and used active FDI to power GDP growth at up to 11.5% per year.

Moreover, this country sustained high incomes and growth with the sort of net migration NZ has targeted but constantly overshot — about 33,000 people in the last statistical year.

I almost moved there during my European stint. But I hate cold climates and like to be further south.

So you’ve probably guessed: I’m talking about the Republic of Ireland, the Celtic Tiger that rose and crashed but has maintained enviable levels of wealth.

And the reason I’m writing about Ireland and foreign direct investment is due to a comment Paul Goldsmith — National’s finance spokesman — made at the Financial Services Council’s annual conference:

‘If we rely purely and solely on our domestic savings, then that’s fine – we’ll grow slowly because there’s not much of them. If we want to grow faster, we need to import capital as well.’

National has been critical of the Government’s foreign capital restrictions, including banning foreigners from buying homes.

Yet, they don’t seem to have a plan for foreign investment. Setting a vulnerable market like domestic housing afloat on the global markets seems a recipe to ensure many New Zealanders are priced out of key areas like central Auckland.

Instead the conversation we need to have is where can we use FDI (foreign direct investment) to power our economy? Ireland had that conversation. It was the lead-up to its Celtic Tiger years. And the reasoning went like this:

‘We’re on Europe’s doorstep and part of the EU. We have an educated workforce. We can be the hub for US and multinational businesses to locate their European head offices. And we can offer the lowest corporate tax rate of any major jurisdiction in the EU to achieve that.’

The rest is history. Intel, Boston Scientific, Dell, Pfizer, Google, Hewlett Packard, Facebook, Johnson and Johnson and many more chose Ireland for their European base. And even during the downturn, they continued to invest.

Of course, New Zealand is not on the EU’s doorstep. Nor does it have much head-office location benefit in any particular region. That role locally is usurped by Singapore. And Sydney, to a lesser degree.

We do have competitive advantage in food production, food technology, agricultural technology and a rising software/ICT sector. Not to mention some very innovative people.

But with some of the highest corporate tax rates in the OECD, alongside rising compliance burden on businesses, we don’t seem well-positioned to attract meaningful FDI. Except for wealthy migrants wanting a retirement bolthole here.

It seems to me neither side of government has an enticing FDI strategy. In truth, next year, I’m struggling with who to vote for. Possibly, if the economic environment doesn’t improve, some will vote by moving across the Tasman.

What you can do as an investor, though, is position yourself to take advantage of New Zealand’s key sectors that are ripe for investment.

In a country of 5 million people, able to feed some 50 million in a hungry world, food production remains a strong, defensive and profitable choice.

If you missed out on the rise of a2 Milk [NZX:ATM], one alternative that could rise with growing investment is Synlait Milk [NZX:SML].

The price has been down due to issues around the Pokeno plant and the seasonal nature of dairy prices. While these remain risks, there’s potential upside.

In fact, the success of Synlait is closely tied to a2 Milk. What most people don’t know is that Synlait holds the exclusive rights as the manufacturer for a2 Milk’s legendary infant formula. This partnership has clearly paid dividends for both Synlait and a2 Milk.

Another option is a favoured stock of mine — Sanford [NZX:SAN].

The holdings of commercial fishing quota present a unique asset in a world moving to healthy diets and fish. Of course, this business is also subject to seasonal risk via catch volume and mix.

In our premium newsletter, Lifetime Wealth Investor, we look at opportunities worldwide where investment can generate meaningful results and dividends. And we show Kiwi investors how to access them.

Right now, the Celtic Tiger does have a worry on the horizon: Brexit. A no-deal outcome there could impact Ireland more than any other country.

New Zealand is on the opposite side of that coin. And according to British Trade Secretary Liz Truss, we’re first in line for a free-trade agreement (along with the US and Australia) with a new, independent UK.

Potentially, we could replace EU providers as a go-to source for the world’s best food and wine.

Here’s to that. And hopefully more.

Regards,

Simon Angelo

Editor, WealthMorning.com

Important disclosures

Simon Angelo owns shares in Sanford Ltd [NZX:SAN] via Wealth Manager Vistafolio.

Simon is the Chief Executive Officer and Publisher at Wealth Morning. He has been investing in the markets since he was 17. He recently spent a couple of years working in the hedge-fund industry in Europe. Before this, he owned an award-winning professional-services business and online-learning company in Auckland for 20 years. He has completed the Certificate in Discretionary Investment Management from the Personal Finance Society (UK), has written a bestselling book, and manages global share portfolios.