When I was in business in 2010, we won a trip. The Welsh Assembly Government flew us to Cardiff to compete for space in their innovation centre.

The flights were to be business class. Previously, there had been a banquet dinner at a swish hotel.

But it was after the financial crisis and Britain was suffering.

First, the flights got downgraded to economy. Then the trip was off. Then back on again. Finally, when we arrived on economy, the banquet dinner became a lunch of Sainsbury’s sandwiches with a cup of tea.

In the meetings that followed, one of the centre heads disappeared for half an hour to ‘collect some information’ we’d requested. He came back with no information and sleep creases across his face.

The whole experience served to put us off doing business in Britain.

So, when I was living there some five years later, often commuting to London’s finance district, Brexit was an event I thought could reinvigorate the UK.

The Brexit opportunity

In 2016, against the mainstream polls, Britain voted to leave the EU. If you read the mainstream financial press, you may think this means the end of the UK. The country will be mired in recession and lost years for the next decade.

In fact, it presents some opportunities:

1. Innovation

The EU stands in the way of innovation. Creators of new technologies must prove to EU regulators their invention is safe. New standards and ways of doing things must then be ratified by 28 countries. When Britain spearheaded the scientific and industrial revolution more than a century ago, Continental Europe was a wary competitor, not the arbiter of standards.

The EU has been or is in the process of regulating AI, Internet of Things, robotics, GM crops, and the shape of bananas sold in stores.

Against this, the light regulatory touch of the US has created the main tech giants of Facebook, Google, Apple, and Amazon. It is telling there are no tech giants in Europe to rival them.

2. Control of borders

Australasia has benefited from economic migration. We choose people with money. People who fit our skill shortages and can inject capital and ambition into our economies. Here in New Zealand, we’ve over-relied on it to support our economy and the Auckland housing market. But you can’t argue with the fact that money has flowed in.

The UK, as a member of the EU, has far less choice on migrants. Essentially, it is forced to share a free border with all member states, including many poorer countries. The result? There are 3.8 million non-UK nationals from the EU living in Britain.

They have taken migrant places the UK could have used to recruit some of the best, brightest, and wealthiest people from around the globe.

3. Trade opportunity

Free access to the single market is the EU’s self-proclaimed nirvana. Theresa May appeared petrified of losing that access, which is why her deal made untenable compromises.

Only 8% of UK companies trade with the EU — accounting for 12% of GDP. In 2017, the UK had a £67 billion trade deficit with the EU.

Meanwhile, the UK cannot enter free-trade alliances with other countries. Donald Trump has touted a free-trade agreement between the US and the UK, should the country be able to do so.

We are also getting a glimpse of what less access to the single market could look like.

In the first quarter of this year, factory output in the UK increased 2.2%, the strongest quarterly performance since 1998.

Factories are making and stockpiling ahead of Brexit. The key is that the UK imports more products from the EU than it exports to the bloc. Should that trade get disrupted, it will force more local production and imports from further afield. [openx slug=inpost]

Bucking the Brexit gloom

Economic forecasts paint a grim picture. Government forecasts suggest Britain’s GDP would be 10.7% lower in 15 years’ time if it left the EU without a deal, as opposed to remaining in the bloc.

Yet, these forecasts fail to consider how the country may seize the opportunity or manage the threats.

Approaching the 31 October deadline, the UK has been adding jobs.

In the first quarter of this year, Britain added 32,000 jobs, reaching a record high of 32.75 million people in work.

With among the lowest unemployment rate in the world at 3.8%, the British job market has opportunity written all over it.

Without a free moving source of EU labour, wages will rise. A new immigration policy will be required to make the country competitive. Migration can be used to fill skill shortages while bringing in capital from faster growing regions of the world.

Although Brexit was about reducing immigration, numbers have remained strong with a net gain of 283,000 people ‘planning to stay 12 months or more’ in the last year.

Non-EU net migration has increased, while EU net migration has decreased.

So, it seems the UK remains an attractive enough destination to resolve its skill shortage by tapping migration outside of the EU.

Throughout 2018, gripped with Brexit uncertainty, the UK economy still grew 1.3%, beating Germany, France, and Italy.

Opportunity in the markets

If Brexit may not actually be that bad, why are the markets so worried?

The pound is weak. At the time of writing, GBP.NZD runs at around $1.93. Prior to Brexit, it was as high as $2.43. And the Kiwi itself is weak, as manufacturing and our key housing market slows.

The London Stock Exchange appears one of the few markets where stocks still sell at relatively low valuations.

For example, key domestic bank Lloyds [LSE:LLOY] currently sells on a P/E of around 10.55 and dividend yield of 5.56%.

Compare even the beleaguered Aussie banks with P/Es around 13.5-16.

Aviva [LSE:AV.], one of the world’s largest insurers today, sells on a P/E of 10.81 and dividend yield of 7.34%.

Multinational insurer AIA [HKG:1299] sits on a P/E of 43.72 at time of writing.

One reason for the value is that most of the market looks at the short-term (12-month) outlook. And these traders cannot stand uncertainty.

Over the next 12 months, Brexit could hurt values across the FTSE.

Yet, the long-term (five-year) outlook is that value is value. And should the UK be able to find advantage in its new position outside of the EU, prices could take off.

Of course, you must be prepared to take that risk. The truth is we don’t know what will happen once the UK leaves — and right now, how they will leave.

As with most things in life, fortune favours the bold…

Bold BoJo

It always seemed odd to me that Theresa May was trying to get a deal for something she never originally believed in. In the months before the 2016 referendum, she was in the Remain camp — although quiet in her campaigning.

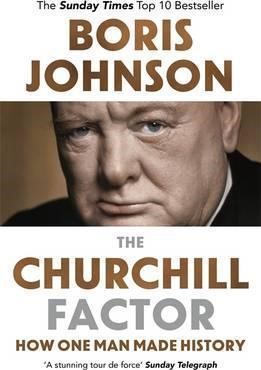

Boris Johnson (BoJo) is the frontrunner to take over the leadership of the Conservative Party.

He was a key figurehead for the Vote Leave campaign back in 2016. He has insisted that Brexit will go ahead at the end of October, but his preference is to make a deal.

BoJo touts a remarkable record during his two terms as Mayor of London. He claims to have cut the murder rate by 50%, cut road traffic fatalities by 50%, built more than 100,000 affordable homes, and lifted the poorest London neighbourhoods out of the bottom 20.

Bojo says he has helped ‘unite our capital, the greatest city on earth.’

Can he make Brexit work?

Crucially, he is more popular with Conservatives than May ever was. He is more likely to get a deal over the line.

And there’s timing. By now, the EU is exhausted with Brexit. Theresa May was one of their hens seeking to leave the coop. BoJo is a fully-fledged Eurosceptic fox.

Fail to feed him something and he could well take Britain out of the EU with no deal. Forced by calamity to deregulate, cut taxes, and find a Singapore-styled economic path led by London, the UK could become the EU’s worst nightmare.

Should Britain succeed outside of a deal, frustrated Italy and others might want to follow suit.

Whatever happens, this year is going to be one of the most interesting on the London Stock Exchange and for the pound.

A deal will boost both. No deal will plunge both down even further.

But what is the real downside? Here in Australasia, we have no deal with the EU. Yet there are no shortages of food, medicine, or widespread civil unrest.

In the event of a no-deal Brexit, there would be a difficult period of transition.

But this is not World War II. If BoJo can bring about a Churchill moment and lead the country through this travail, it could be the shot in the arm the UK needs.

Regards,

Simon Angelo

Analyst, Money Morning New Zealand

Important disclosures

Simon Angelo owns shares in Lloyds Banking Group plc [LSE:LLOY] and Avivia plc [LSE:AV.] via wealth manager Vistafolio.

Simon is the Chief Executive Officer and Publisher at Wealth Morning. He has been investing in the markets since he was 17. He recently spent a couple of years working in the hedge-fund industry in Europe. Before this, he owned an award-winning professional-services business and online-learning company in Auckland for 20 years. He has completed the Certificate in Discretionary Investment Management from the Personal Finance Society (UK), has written a bestselling book, and manages global share portfolios.