Last week, a group of globalists had talks behind closed doors.

In their hands is the concentrated power to create money, disturb financial markets and ruin household wealth.

The latter they’ve already done.

Maybe the name Anthony Scaramucci is familiar?

He’s the co-founder of two hedge funds. He’s an author. But maybe his biggest claim to fame is as ex-communications director to President Trump.

And last week at the Grant’s 2019 New York Conference, I had the chance to hear from the man himself.

While he had a lot to say about Trump, he also touched on the destructive nature of central banks.

Anthony grew up in a working family. His dad was a blue-collar worker and stayed that way for lack of education. This is still the reality for a lots of Americans and Aussies.

Problem is they’re getting paid almost 35% less, in real economic terms, than their 1970’s forbearers. Yet this probably comes as no surprise. Increase the supply of something (money) and it becomes a whole lot less valuable.

So what are you going to do if central bankers continue to destroy the value of a dollar?

Buy stocks?

The globalists are against you

One of the problems, according to Jim Grant, are the heads filling up central banks. They’re all theorists and PhDs with very little practical knowledge.

It’s why we have inflation targeting. Let me explain…

We all know what inflation is. It’s generally associated with growth and good things. It means that asset prices (generally) are on the up and up.

Who doesn’t love that? Inflation means the value of your home goes up. Your stocks and investments go up in a world of inflation.

But if I define inflation another way, it doesn’t sound so great. You could also say inflation erodes the value of a dollar. The reason why that doesn’t sound good is because we all get paid in dollars.

This was more or less Scaramucci’s point at the NY Conference. Inflation has chipped away at family wealth thanks to central banks and their enthusiasm to print money, and wages haven’t kept up.

When you put it in this context, inflation doesn’t sound too good at all.

As a side note, this is one of the reasons why Scaramucci thinks Trump won the election in 2016 when no one else thought he could. The globalists, the media, they were all rooting for Hillary.

They thought she would win because they saw a completely different world. One where workers were doing OK, but would like a few more handouts.

Trump, on the other hand, saw the real US. It is filled with people like Scaramucci’s dad, blue-collar workers suffering at the hands of central bankers.

But back to inflation…

Why do we have inflation targeting if it’s inflation that erodes wages and wealth for millions of people? Well, it’s like Jim said. We’ve got all these theorists and PhDs behind the money printers. And to them, deflation is the worst thing in the world.

But that’s not always the case, according to Richard Sylla, another speaker at Grant’s NY Conference. In a fireside chat with Jim, Sylla discussed the last 3,000 years of interest rates.

‘Easy money [low interest rates] does not always lead to a stimulated economy,’ he said. It reminded me of the Charlie Munger saying: when people say common sense what they’re actually mean is uncommon sense.

The conventional idea is that easy money does stimulate an economy. It’s almost thought of like a rule, even in financial circles.

But as Sylla explained, this isn’t always the case. The world is not made up of absolutes. There are far more contingent circumstances than central bankers are willing to admit.

The same applies to deflation. A dirty word to most, but is it really all that bad?

Letting prices fall and the value of a dollar appreciate might actually be something we need right now. It could boost wages, in real economic terms, it could put a damper of sky-high asset prices.

The PhDs won’t let it happen, though. They’re scared by a potential Great Depression 2.0. So they target not 0%, but 2% inflation. They’re so frightened of deflation they’re willing to erode your money by 2% a year just so they don’t come anywhere near it.

With this in mind, what is it you should be doing? If the heads of the printing press are going to keep printing money to create inflation, why not get your wealth out of cash and into stocks? [openx slug=inpost]

The myth about stocks for the long-term…

Buying a broad index of stocks might not do it, though.

According to Edward McQuarrie, who also presented at Grant’s 2019 NY Conference, the 6–7% long-term returns we all expect from stocks might be a tad misguided.

That’s because we all listened to Jeremy Siegel, author of Stocks for the Long Run. In his book, Siegel compares the returns of stocks (thought of as a risky asset class) to bonds (a less risky asset class).

Over a period from 1802 to 2012, Seigel found stocks comfortably beat bonds and generate an annual return of 6.6%. Again, this is all thought of as common sense in financial circles.

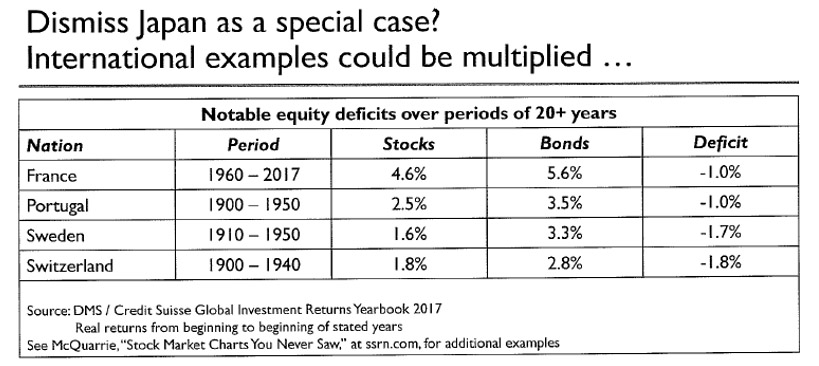

Yet McQuarrie was there to tell us, it just isn’t so. And in fact, if you take out extraordinary events and fix up the shabby bond index Seigel was using, then bonds actually beat stocks for multi-year runs.

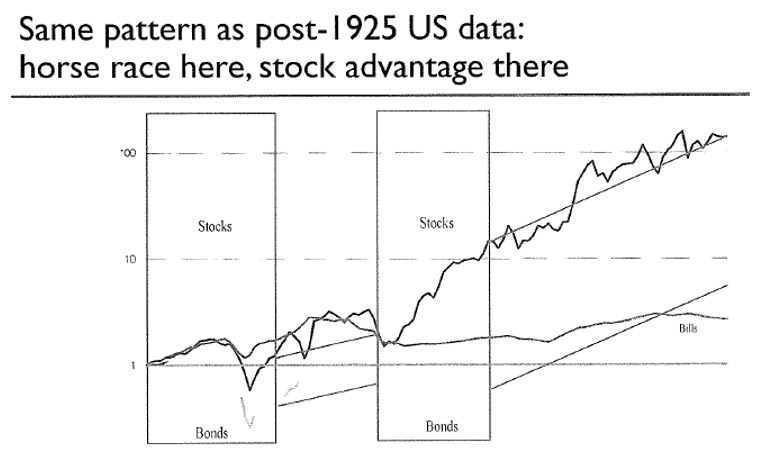

The reason why stocks have done so well, according to McQuarrie, is because of a few events in history. Take a look at this graph…

That first period, when bonds dropped far more than stocks, was around the 1929 crash. The second period, when stocks ran up dramatically, was just after the Second World War.

It’s these two events, McQuarrie said, that has imprinted the idea on investors that stocks do great in the long run. But take these two events away and it becomes a horse race between stocks and bonds.

Again, what does this mean for you? I believe it means you not only have to buy stock to protect yourself against inflation, but you need to buy the right stocks. The good, cheap businesses…

Or Jim might also tell you gold is always an option…

You decide.

Your friend,

Harje Ronngard

Harje Ronngard is one of the editors at Money Morning New Zealand. With an academic background in finance and investments, Harje knows how difficult investing is. He has worked with a range of assets classes, from futures to equities. But he’s found his niche in equity valuation. There are two questions Harje likes to ask of any investment. What is it worth? And how much does it cost? These two questions alone open up a world of investment opportunities which Harje shares with Money Morning New Zealand readers.