Have you been keeping up with all the high-tech news at CES?

CES, or the Consumer Electronic Show, is the biggest and best bash for geeks the world over.

At the convention are names like Google, NVIDIA and Sony. They’re all strutting the coolest futuristic projects they’ve been working on.

What was on show this year, you ask?

Up and comer UBTech was showing off what I’d describe as a robot butler. It can help with cooking and cleaning. If you want a can of coke from the fridge or need to wash the dog, it can do that too.

Another cool booth was showing drug-free pain relief. The Oska Pulse is a small device that can fit in your back pocket. It produces electrical impulses. These impulses have a radius of about 22 inches, reducing any inflammation within that area.

For John Davidson over at the Australia Financial Review however, CES has been all about the cars…

‘It’s not just car entertainment systems that are everywhere you look here at CES. It’s car driving systems, too, the very guts of the cars, that are in just about every hall of the sprawling, 250,000-square-metre show.’

One vehicle that caught my eye was John Deere’s RoboFarmer.

It’s an autonomous combine that can follow a pre-set GPS route. The company says the combine will stay on path, deviating only 2.5 centimetres at most.

Say goodbye to even more farm workers…

Tech is pushing us out of jobs

I’m not a technology nihilist. I don’t believe technology will rise up against us and thwart the human race.

But tech of all shapes and sizes is pushing a lot of us out of jobs. Take farming for instance.

In 1900, 41% of Americans were working on the farm. It was their livelihood and their life.

‘These farms employed close to half of the U.S. workforce, along with 22 million work animals, and produced an average of five different commodities,’ a 2005 paper from the US Department of Agriculture cites.

Fast forward 30 years and that level of employment is about half. Another 15 years after that and about 16% of the population were farm workers.

Jump to 2002 and less than 2% of Americans man the farms.

What happened in that time?

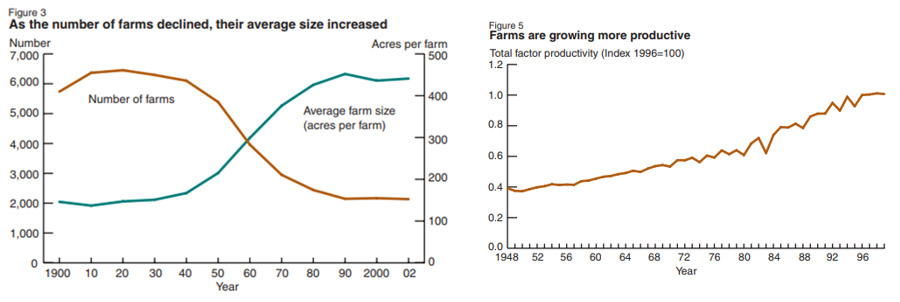

The US got extremely efficient at producing large quantities of food. They now produce far more food on far fewer (but larger) plots of land.

|

| Source: The 20th Century Transformation of U.S. Agriculture and Farm Policy |

And it’s all thanks to companies like John Deere. They come out with new and better equipment. Others develop new and more resistant seeds.

Over time, the farming industry gets a whole lot more efficient (as you can see in the graph above). Production outstrips demand year-on-year.

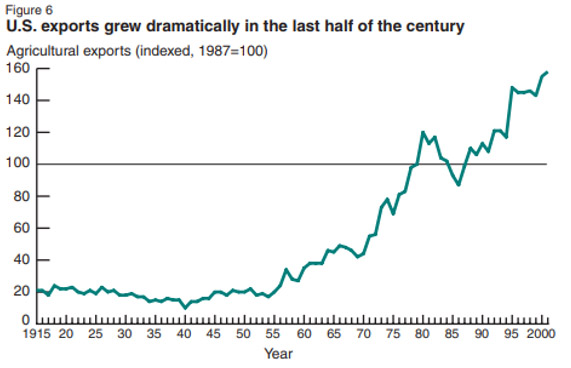

So what happens with all this excess supply? It goes to places like China.

|

| Source: The 20th Century Transformation of U.S. Agriculture and Farm Policy |

Was this a bad thing that so many famers lost their jobs? Not at all.

They found new jobs, largely thanks to the war efforts in the 1940s. But that’s a whole other story…

The American population is now working in far better conditions. They’re also producing goods and services that are far more valuable than crops.

And like farming, I believe you’ll see a similar situation play out for manufacturing.

China’s big struggle manufacturing

What’s happened for agriculture is already happening to manufacturing. Output is going up. Employment is going down.

It does not go up forever, though. Like demand for food, there is a ceiling. China will find that out the hard way.

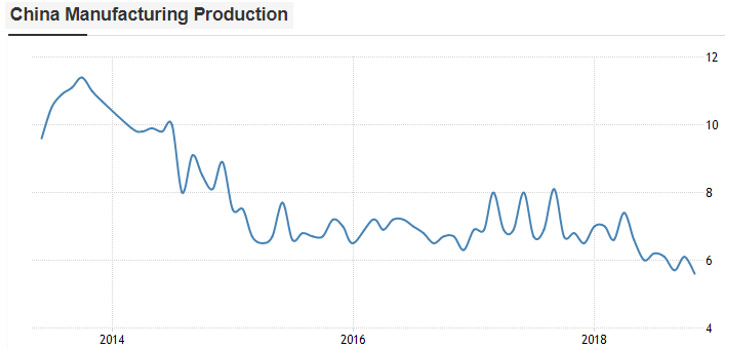

|

| Source: Trading Economics |

Factories in China have gotten a lot better at producing stuff. They can produce more of it with less workers. An industry that was once growing well above 10% is now growing below 6%.

And it’s not just China. Manufacturers around the world are getting better each year. And they’re requiring less workers to do the same job.

From the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE):

‘…Robert Lawrence finds that the decline in manufacturing employment in the United States, European Union, and Japan is largely, if not entirely, the result of changing patterns of demand—as incomes rise, the demand for goods rises relatively less than that for services—and faster productivity growth in manufacturing.

‘He has shown that the decline in the share of the labor force employed in manufacturing in the United States is hardly unique. It is a trend that is evident in all industrialized countries, even those with large trade surpluses, notably Germany.’

The effects have not taken effect in China as quickly, though. Employment is shifting towards the service sector, which made up 32% of the population in 2007 and is now 45% of the population. But employment hasn’t decreased from the industrial sector all that much.

If anything manufacturing employment is up in China. PIIE continues:

‘Manufacturing employment did dip by 18 million or almost a fifth between 1995 and 2000, a period when the then Premier Zhu Rongji pushed through a far-reaching reform that resulted in the closure of thousands of inefficient state-owned firms. But as the effect of this reform waned, manufacturing employment rose steadily, not only in absolute numbers but also as a share of total employment.’

Why is China bucking the trend? They just haven’t reached that turning point yet. But in time, they will.

It’s why the policy makers need to make some tough decisions. And they better make them fast. They’ve got to move hundreds of millions of people out of the factories and into the cities.

Mind you, market forces will take care of this naturally. As manufacturing output exceeds demand, manufacturers will hire less, forcing people to move to where the jobs are (the service sector).

But if China wants to keep their economy humming above 6%, they’ve got to speed the process along.

What’s the end game here?

The end game to all this is the opposite of trade and the opposite of globalisation.

Everyone will be efficient at everything. Tech, like the stuff we see at CES, will pave the way for a local world, where local producers cater to local buyers.

This trend will keep happening whether there are trade tensions or not, I believe. I think it will continue whether interest rates are up or down. It will happen whether you like it or not.

And it’s because new technology is helping us get better at everything.

Localisation is coming,

Harje Ronngard

Harje Ronngard is one of the editors at Money Morning New Zealand. With an academic background in finance and investments, Harje knows how difficult investing is. He has worked with a range of assets classes, from futures to equities. But he’s found his niche in equity valuation. There are two questions Harje likes to ask of any investment. What is it worth? And how much does it cost? These two questions alone open up a world of investment opportunities which Harje shares with Money Morning New Zealand readers.