Back in September 2017, the US Federal Reserve was quite optimistic. They had just announced that they would start unwinding their stimulus program.

To give you a bit of background, central banks reduced interest rates close to zero and increased the size of their balance sheet to stave off the 2008 crisis.

10 years after, the economy was going well.

The Fed had already started to increase rates in 2016 and were looking at starting to reduce the size of their balance sheet in an effort to get back to normal.

This was an unprecedented program…much like it had been decreasing rates close to zero and increasing their balance sheet 10 years earlier.

That’s why they were planning to ‘normalise’ monetary policy very slowly.

They didn’t expect much turbulence. As the then US Fed Chairman Janet Yellen said, she hoped the unwinding would be as boring as ‘watching paint dry’.

The truth is that it’s not shaping out to be that way.

Markets have been jolting all year. We have seen turbulence in emerging markets, Europe and the US as investors look to reduce risks.

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) released their quarterly review. If you are not familiar with the BIS, it is the bank of central banks. Their reports give some insight in the thinking behind the central banks.

The BIS doesn’t see these ‘market tensions’ as isolated events, but as part of the journey to monetary normalisation. And as Claudio Borio, BIS’ head of the monetary and economic department, said, we should get ready for more:

‘It was not the first, and it will not be the last. It was just another bump along the narrow path of monetary policy normalisation.’

Why are markets in turmoil?

Well, one of the fears is increasing rates. There is a lot of debt out there and rate increases will make it more expensive. The other main worry is a trade war between the US and China.

The normalisation has made markets jumpier than normal, as Borio explained:

‘Indeed, the uncertainty that surrounds the unprecedented monetary policy normalisation process no doubt makes markets more sensitive to such developments.’

Add to that the worries about Brexit and Italy, and anything could pop this bubble we have been living on for the last 10 years. [openx slug=inpost]

As we heard from the BIS, record low interest rates have affected one aspect in particular, and it is one area that worries them. As they noted:

‘[N]owhere are easy financial conditions more evident than in the leveraged loan market, which continues to be overstretched. And the bulge of BBB corporate debt, just above junk status, hovers like a dark cloud over investors. Should this debt be downgraded if and when the economy weakened, it is bound to put substantial pressure on a market that is already quite illiquid and, in the process, to generate broader waves.’

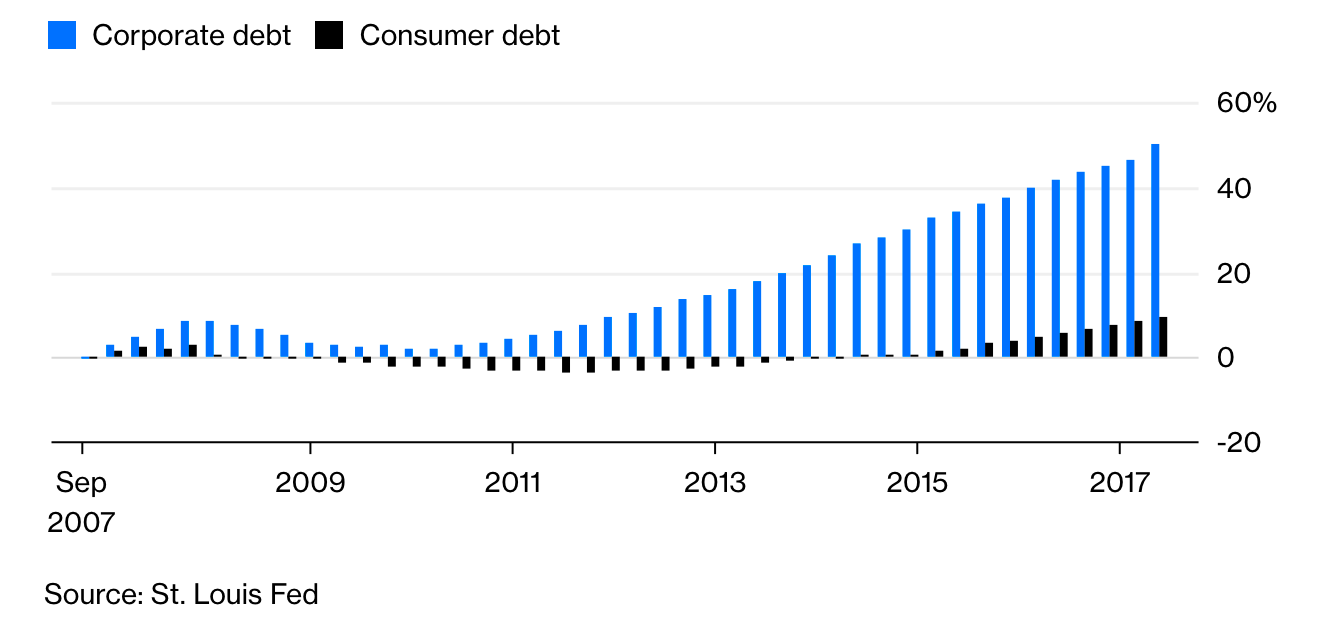

Cheap debt has meant that corporations have been binging on debt. As you can see in the graph below, corporate debt has been booming in the last few years due to low interest rates. Increasing interest rates could definitely affect this.

|

| Source: Bloomberg |

It’s something that worries the US Fed too. As they noted in a recent report:

‘High leverage has historically been linked to elevated financial distress and retrenchment by businesses in economic downturns. Such an increase in financial distress, should it transpire, could trigger a broad adjustment in prices of business debt.’

The Fed is looking to get rates to 3% and unwind their balance sheet to prepare for the next crisis.

But we could hit trouble well before they reach their goals, whether inflation appears…or not. As Borio continued:

‘These and other financial vulnerabilities deserve close attention. This is not only because, should inflation at some point rise more than expected, they would further weaken an economy saddled with higher policy rates; but also because, as experience indicates, even if inflation did not raise its ugly head, a downturn could take place. In fact, since the early 1980s economic downturns have been triggered more by financial booms gone wrong than by monetary policy tightening to quell inflation flare-ups.’

Rates are quite low still compared to historical averages. Markets are now expecting the Fed to increase rates one or two more times instead of the three they had promised.

If inflation shows, we could see more rate hikes ahead, making all that debt more expensive.

It it doesn’t, then the fed could waiver on their resolve midway, especially if there is more turmoil ahead. We could then see interest rates stay low for a long time.

The problem is that we see valid arguments for both possible scenarios.

Either way, getting things ‘just right’ won’t be that easy.

Best,

Selva Freigedo

Subscribe Now

Subscribe Now Login

Login Managed Accounts

Managed Accounts Quantum Wealth

Quantum Wealth