69%.

That’s how many stock pickers have failed to beat the ASX200 over a five year stretch.

What makes it worse is the market’s terrible performance in the recent past.

From 2015 to 2016, the market was down 2.6%.

From 2016 to 2017, it was up 13.5%.

And from 2017 to 2018, Australia’s largest 200 stocks were up 5.4%.

On a compounded average basis that’s a 5.7% return. Is this something you’d be happy with?

Yet a large majority of professional stock pickers can’t even beat that!

Should we all just buy ‘the market’ and be done with it?

Why aren’t we all passive investors?

The figures get even worse as we extend time.

According to a recent S&P Dow Jones Indices report (my emphasis):

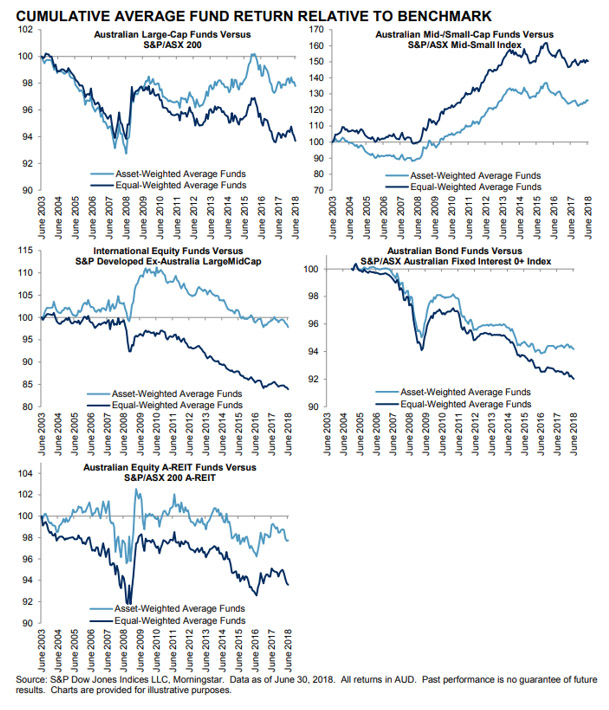

‘We have consistently observed that the majority of Australian active funds in most categories fail to beat their comparable benchmark indices over the long term.

‘Over the 10-year period ending June 30, 2018, almost 90% of international equity funds and more than 70% of Australian equity general, Australian bond, and A-REIT funds underperformed their respective benchmarks on an absolute basis. In contrast, more than half of Australian small-cap funds beat their benchmarks.’

|

Source: SPIVA Australia Mid-Year 2018 |

Clearly there are a lot of asset managers not doing their job.

The growing trend of ETFs

I guess you can’t really blame investors jumping out of active and into passive investments. One passive vehicle growing in popularity is exchange traded funds (ETFs).

Within an ETF is a collection of assets: stocks, bond, commodities…fees typically tend to be lower and the returns seem to be better than what many active managers can achieve.

The whole ETF market has balloon from US$728 billion to more than US$5.6 trillion.

A recent study has even suggested that passive investments like ETFs make the market smarter. And by smarter, I’m going to assume they mean more efficient: where market value and intrinsic value meet.

Reported by the Australian Financial Review (AFR):

‘At the UBS quant conference in Sydney last week Professor Talis Putnins, of the University of Technology Sydney and the Stockholm School of Economic presented the findings of a paper titled The Active World of Passive investing, which he co-authored with David Easley from Cornell University and UTS colleagues David Michayluk and Maureen O’Hara.’

One benefit of ETFs, according to Putnins is liquidity. Because ETFs buy and sell a wide variety of shares, bonds, etc. it increases liquidity for those particular assets and encourages short selling.

This is when an investor borrows a stock they don’t own (in this case from the ETF) and sells it in the market. The hope is that they can buy the stock back (returning it to the ETF) for a lower price.

How does this make the market smarter?

Short sellers usually go after two types of stocks: those which are extremely expensive and those which are frauds.

The perfect short is a stock which is both of the above.

With more short sellers in the market, it becomes harder for market prices to get out of hand and pulls them closer to intrinsic value.

Putnin also points out that EFTs may even have active attributes, adding to informational efficiency. The AFR continues:

‘While all ETFs are designed to track an index, in the majority of cases, these indices are constructed so that the investor can make an active bet on a sub-set of the market, an industry, a theme or even a factor.

‘In fact, in the US “active” ETFs dominate the number of funds on offer (with 84 per cent defined as very active) and by dollar volume (with 86 per cent defined as very active). By assets under management, 58 per cent of US ETFs are moderately or very active while 10 per cent are very passive.’

So are you convinced? Do you think ETFs make the market smarter?

I hope your answer is no. If it isn’t, then consider the following… [openx slug=inpost]

How ETFs distort the market

Firstly, we can’t expect a majority of active manager to beat ‘the market’. There has to be at least 50% of managers that do worse than the average, simply because they make up the average.

I also believe active performance has declined due to a shift in how the industry generates returns.

Business financials are no longer the be all and end all.

There are hundreds of thousands of managers investing huge sums on factors like volatility, or beta. Others are looking at correlation or trying to guess what prices will do next with a bit of charting.

There’s nothing wrong with the above. Some of it can improve your short-term performance. But for the long haul it can be very damaging.

It’s why the number of managers that beat their benchmark drops significantly as you extend time.

Secondly, ETFs do distort the market.

Take one of the most popular ETFs, the SRPDR S&P 500.

The fund tracks the S&P 500 and holds assets in a blended style. This means the weight of each stock is determined by value and growth characteristics.

How they boil down value and growth into one equation I have no idea. But consider what happened when investors buy and sell the SRPDR S&P 500.

What they’re actually doing is buying and selling units.

To add units, the SRPDR S&P 500 has to buy more of the S&P 500. To remove units (redeeming sellers), the SRPDR S&P 500 has to sell its holdings.

So depending upon the number of buyers and sellers, the SRPDR S&P 500 will be distorting those stocks it considers to be of the highest ‘value’ and ‘growth’.

In a situation where stock prices are declining rapidly, an ETF can add to declines.

As stock prices decline, the unit value of the ETF declines. Paper losses could encourage some investors to sell, causing the SRPDR S&P 500 to sell its holdings.

This added selling pressure pushes stocks within the SRPDR S&P 500 down lower, causing more unit holders to sell and more selling from the SRPDR S&P 500.

And because the SRPDR S&P 500 is weighted towards the best value and growth stocks among the S&P 500, the ETF is actually selling more of the stocks it considers to be bargains.

Surely if this ETF was smart, it would buy the best and sell the worst?

But that’s just not how these investment vehicles are set up. And as a result, they could lead to deeper stock declines.

Putnin argues however, that if ETFs lead to market distortions, why haven’t active managers taken advantage?

I believe it’s because most investors don’t want to buy what’s out of favour or stocks that might take years, not months to appreciate.

To improve quarterly returns, they’d rather try to pick the stock still in favour, sucking out what returns they have left.

The last point I’d like to make is one that Putnin has already brought up: the active aspect of ETFs.

Initially you would think this makes the market smarter. Investors are rational (not really) and they act according to new information.

But did derivatives make us smarter?

Many use derivatives to hedge risk. Yet many more use them to speculate on asset prices. I’d argue a good chunk of investors do the same with ETFs.

An ETF is just a collection of prices after all. Why else would you buy and sell an ETF, in a relatively short time if not for some speculative investment thesis.

But maybe Putnin is right.

Maybe ETFs are smarter than active managers. Rather than jumping in an out, ETFs generally try to hold a basket of assets and let time do its magic.

Maybe it’s the investors buying and selling these vehicles that make them inefficient.

Your friend,

Harje Ronngard

Harje Ronngard is one of the editors at Money Morning New Zealand. With an academic background in finance and investments, Harje knows how difficult investing is. He has worked with a range of assets classes, from futures to equities. But he’s found his niche in equity valuation. There are two questions Harje likes to ask of any investment. What is it worth? And how much does it cost? These two questions alone open up a world of investment opportunities which Harje shares with Money Morning New Zealand readers.