In my lifetime, the major tech revolution was the internet.

Email, online banking, shopping, file management and knowledge search transformed everything. And the internet is still getting better as it mobilises, goes social, speeds up and runs deeper.

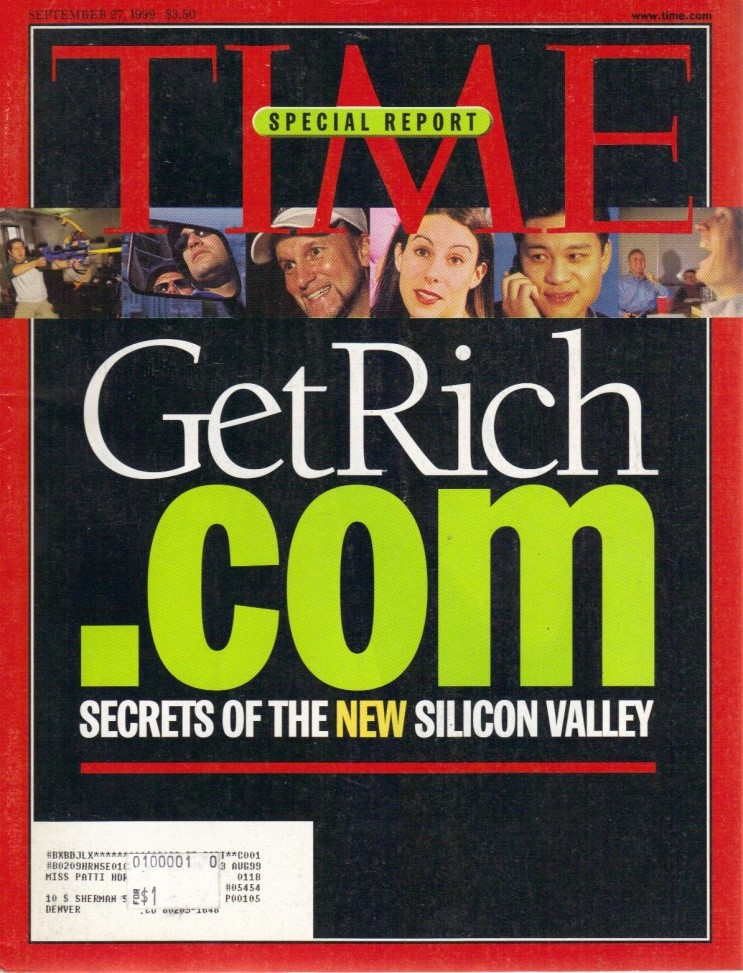

It was the major economic transition of our age. The digital revolution. Highlighted in Time Magazine’s September 1999 edition:

Inspiration

The article inspired me to start an online business in the training space. Which received a significant funding offer from a US VC (Venture Capitalist).

Then the dot-com crash hit.

And the money dried up.

Since then, enduring online businesses like Amazon, Google, Facebook, eBay, Twitter — you can go on and on — have prevailed.

Online tech, with a potential boost from 5G, is now moving from screens and devices into everyday life.

Auto tech is looking to be the next big sector as the internet and GPS combine to perfect self-drive vehicles and harness more benefits from electrification.

That’s juicy. We’re investing in that via one of our Lifetime Wealth portfolio recommendations. And we’re doing so in a managed-risk way.

But here’s what I see is missing…

The digital revolution is solving a lot of problems around information and communication (while creating more). It’s moving into transport and solutions on the move.

But the process of buying, owning — or not owning — a house hasn’t changed much at all. And deep problems remain.

First, there are the costs.

Technology has brought down the cost of almost everything else. Cars are cheaper. So are phones, electronics, equipment and many furnishings.

In fact, we can see this painting a vivid economic picture. Inflation has left the room in most developed economies. Interest rates are tending toward zero to try and avoid the spectre of deflation.

And that’s because we’re getting older. We’re not spending on new stuff. There are less babies being born with 90-odd years of consumption ahead of them.

An ageing population

So, with an ageing population spending less and technology driving down costs, the only elephant in the room is the fact that older people own all the homes. And with little place else to go to get yield on capital, that asset class has hit the sky.

Young people can’t get into house. At least not into a conventional detached picket-fence with a garage, anywhere near a large city.

OK, so smart millennials are finding alternatives. My sister moved out to a smallholding 45 minutes from town with her husband and son. They’re slowly doing up the little cottage. They’re enjoying a low-debt, low-cost vegan lifestyle with a menagerie of animals.

Can tech solve the housing crisis?

If it can, we could be on the cusp of another major investing revolution. And you and I want to be part of that.

So…what crisis?

Maybe you own a house. Have little or no debt. Extra money to invest. That’s because you’re a Wealth Morning reader.

But many younger people are stuck in what I call a ‘Bitchflation’ debt cycle. They’re often paying off student loans. To enter a market like Auckland, they need to take on further debt. Massive debt.

On the North Shore, where I live, the average house mortgage in 2017 for under 55s was $542,600. Probably more now.

As for under 35s — you don’t see them much owning homes on the North Shore, nor near the coast.

The Bitchflation thing comes in — because although there’s not a lot of inflation on consumer goods and tech, there’s been massive inflation in asset classes like homes and shares.

As interest rates de-yield, investors still need income and return. They run rental property. Or buy up the stock market.

Where the government went wrong

Of course, it didn’t help when the Clark and Key governments spent 20 years floating Auckland homes on the global market and ramping up migration to boost GDP. But, on the flipside, with too few babies, we will need more pension payers.

I worry that the CPI (which gives us our annual inflation figure) doesn’t adequately consider housing costs, but that’s a subject for another analysis.

What you do notice is that rents tend to buck the consumer price index.

And the real cost of a house may not be factored — since for many people, 30% or more of their income gets sucked up by it.

Within most countries of the OECD — including New Zealand, Australia and the US — house prices have grown much faster than incomes:

Not sustainable

It’s created an odd investment class of hoarding housing. Often at pretty low yield.

But worse still — it’s created a social and generational divide.

Did you buy in Auckland before 2012? You’re all set, then, aren’t you?

Are you wanting to get in now? It’s a median of 848k for a clapped-out dump on a handkerchief of land.

Do you need to borrow 600k to own a spittoon in the Auckland volcanic field? Go off-grid like my sister, I reckon. Consider Australia or North America, where there’s more urban choice and higher salaries.

Here’s the upside: as with many problems — like the housing crisis — entrepreneurs have the best hope of resolving them.

That’s provided that those entrepreneurs are given an environment to do so.

Housing tech is an emerging area. It’s been very slow. I’ve noticed a lot under the radar.

Business can assist to make housing more affordable and available.

House production

Building a home hasn’t changed much. Foundations. Walls. Roof. A variety of specialist trades. Expensive materials with GST on them. Some sustainable. Some not. A growing council-compliance industry to create jobs for ex-school prefects.

3D printing and necessary regulatory adaption could change the game.

When large 3D concrete printers first came to market, they were expensive. Technological development now looks set to bring costs down to the point where they could revolutionise the building site:

Icon Build is an Austin, Texas-based start-up rising to the challenge.

According to the company, its technology could see it producing single-storey homes in 48 hours for $10,000 or less.

The same technology can be applied to housing components. And apartments, terraces, and reuse on top of and within existing buildings.

Land reuse

But in cities like Auckland, Sydney or San Francisco, the main cost barrier comes down to the price and availability of land.

The value of land comes down to its use. And the yield on that use.

Once the potential yield of surrounding farmland falls beneath what housing or commercial use could generate, there’s an argument that the farms should move further outward. The land should be opened up for housing.

In Australasia, although prime amenity areas are near the CBD, technology beats distance. Good infrastructure development can create vibrant new town centres which can be easier to live in. If they’re near water or a mountain-biking forest — even better!

Another opportunity is that land-use yield changes with the times.

In Britain, we’re recommending a retail-site owner in our Lifetime Wealth programme. It’s maintaining good occupancy across its properties. But with retail oversupply in an uncertain Brexit situation, there’s more upside to add apartments on top of those buildings. Increasing yield. And bringing in more shoppers below.

Appifying

Airbnb started in 2007 when Joe Gebbia and Brian Chesky, then both 27, were struggling to pay their rent.

The rest is history. We’re now monitoring the upcoming IPO.

While Airbnb has helped homeowners cover their costs with an easy rental situation, there’s opportunity to go much further in ‘appifying’ the purchase, rental and ownership of housing. Such that costs can be optimised, even lowered.

Right now, I smell the start of another potential revolution. Millennials are looking for new, innovative ways to solve their housing crisis. From small homes, off-grid, to out-of-the-box thinking to find a new box to live in.

Have you come across any businesses — particularly listed ones with technology — that enables housing? We’d love to know. Reach us on cs@wealthmorning.com

Regards,

Simon Angelo

Editor, WealthMorning.com